Charles Pugh (1887–1953): Liverpool Telephone Pioneer – Family, Last Letter, and Legacy

Charles Pugh was born in 1887, spending his life in Liverpool working as a Telephone Instrument Maker. His story, preserved through family documents, a final letter, and a treasured notebook, reflects the evolution of British telecommunications and working-class life in the 20th century.

Charles Pugh was born in 1887, spending his life in Liverpool working as a Telephone Instrument Maker. His story, preserved through family documents, a final letter, and a treasured notebook, reflects the evolution of British telecommunications and working-class life in the 20th century.

1. Biographical Context and Work Life

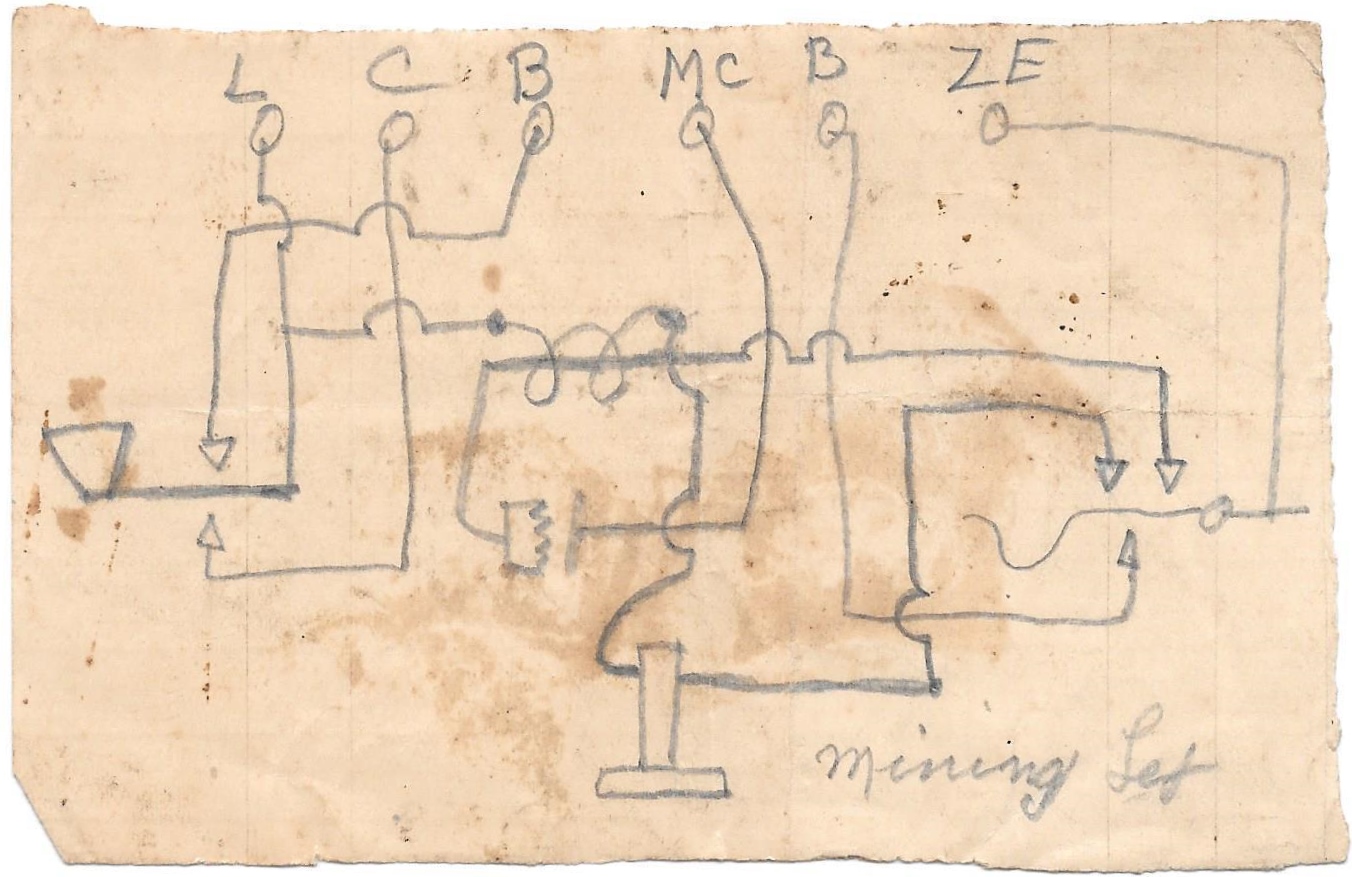

Charles Pugh was born in 1887, placing his formative years in the high Victorian era, but his adult life spanned the Edwardian period and both World Wars. By 1911, Charles is documented as a boarder in Fairfield, Liverpool, working for the Helsby Cable Company as a Telephone Instrument Maker. This occupation was skilled and relatively modern for the time—telephony was an expanding field, and Liverpool was a hub of innovation and trade.

-

Helsby Cable Company: As referenced here, this company played a crucial role in the development and manufacturing of telecommunications equipment in Britain. Workers like Charles contributed directly to the infrastructure that enabled the rapid communications revolution of the 20th century.

2. Marriage, Family, and Domestic Life

On 18 September 1915, in the midst of the First World War, Charles married Elizabeth Henson (known as Bessie, 1892–1988). Their union produced three children—Mabel, Winifred, and Edward (“Ted”).

-

The timing of their marriage—during wartime—suggests a period of anxiety and uncertainty, but also hope and continuity. Their family life would span two world wars and the massive social change of the 20th century.

3. Final Days and Last Letter

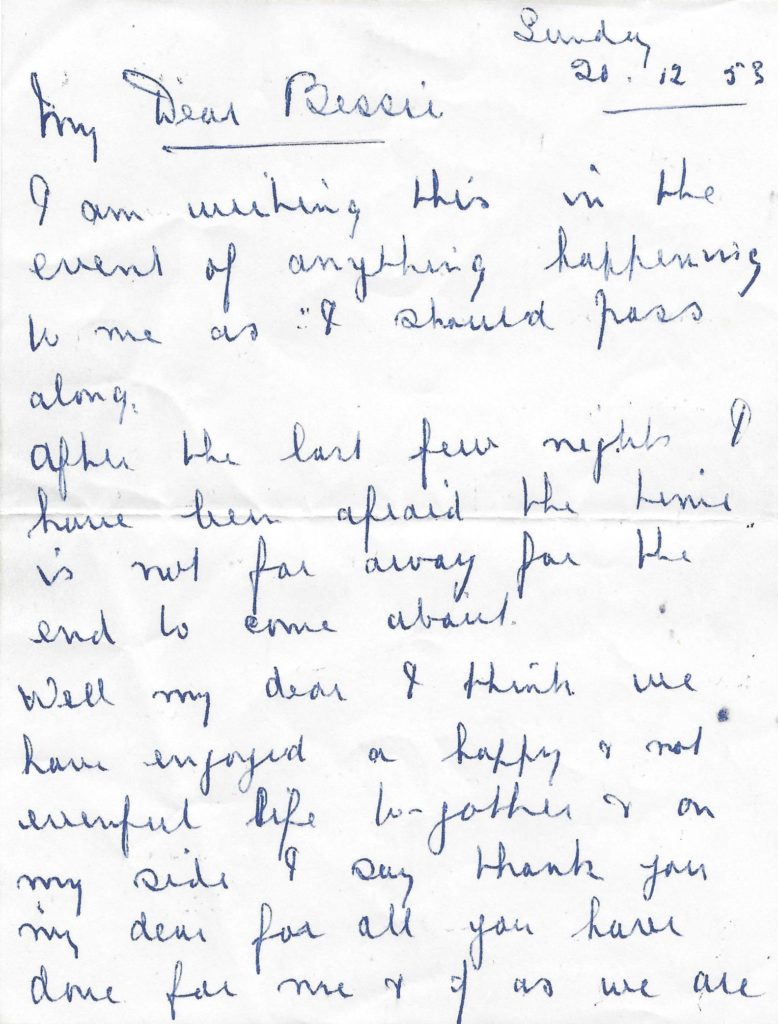

Two days before his death, Charles wrote a note to Elizabeth. The letter is deeply personal and gives insight into his character and their relationship:

“Sunday 20.12.53

My Dear Bessie,

I am writing this in the event of anything happening to me, as I should pass along.

After the last few nights I have been afraid the time is not far away for the end to come about.

Well my dear I think we have enjoyed a happy & not eventful life together & on my side I say thank you my dear for all you have done for me & if as we are told there is another place then surely we shall be happy with one another again.

We my dear here is a list of things.

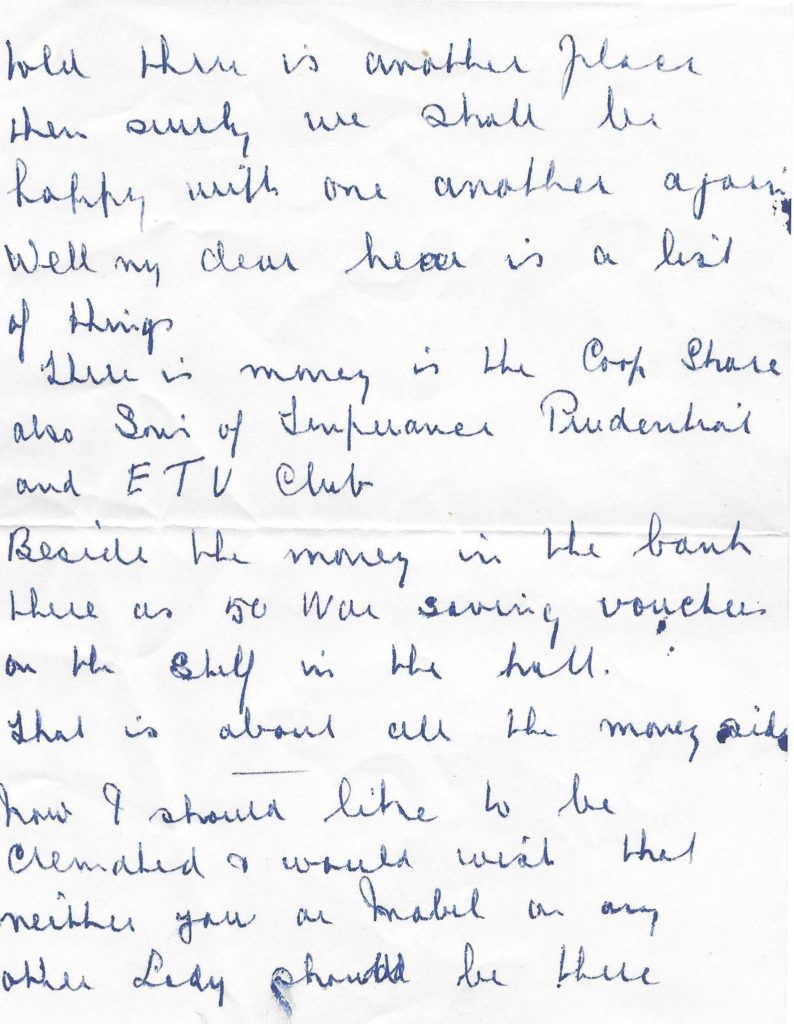

There is money in the Co-op Share also Sons of Temperance Prudential and ETV Club.

Beside the money in the bank there is 50 War Service Vouchers on the shelf in the hall. That is about all the money (?).

Now I should like to be cremated & would wish that neither you or Mabel or any other Lady should be there ”

(the letter ends there).

Analysis of the Letter:

-

Awareness of Mortality: Charles senses his end is near (“after the last few nights… I have been afraid the time is not far away”).

-

Gratitude and Love: He reflects on a life he considered “happy & not eventful,” and thanks his wife for “all you have done for me.”

-

Spiritual Hopes: Charles expresses a belief, or at least a hope, in an afterlife where he and Elizabeth might be reunited (“if… there is another place… we shall be happy with one another again”).

-

Practical Matters: The letter also serves as a practical document, listing financial details (Co-op Share, Sons of Temperance, Prudential, ETV Club, War Service Vouchers), and instructions for after his passing.

-

Wish for Cremation: Notably, Charles asks to be cremated, and for no women—including his wife and daughter—to attend. This is a striking, perhaps protective, request; it may reflect contemporary gender norms around mourning and public emotion.

The letter abruptly ends, possibly due to fatigue or his deteriorating condition.

4. Death, Funeral Notice, and Aftermath

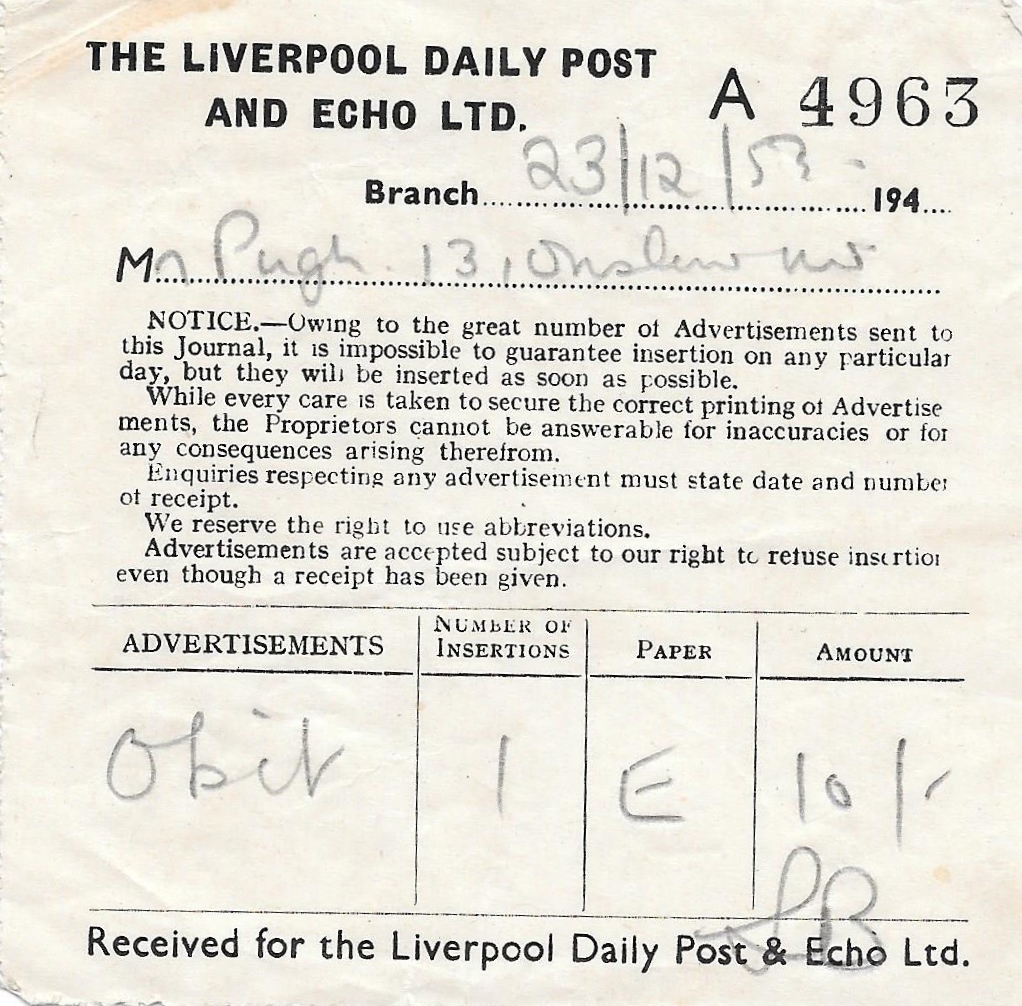

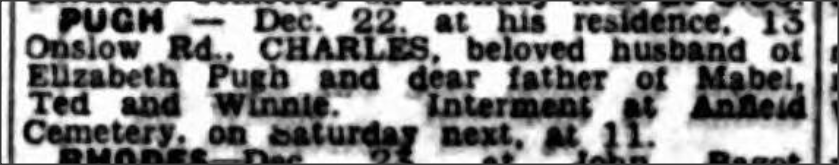

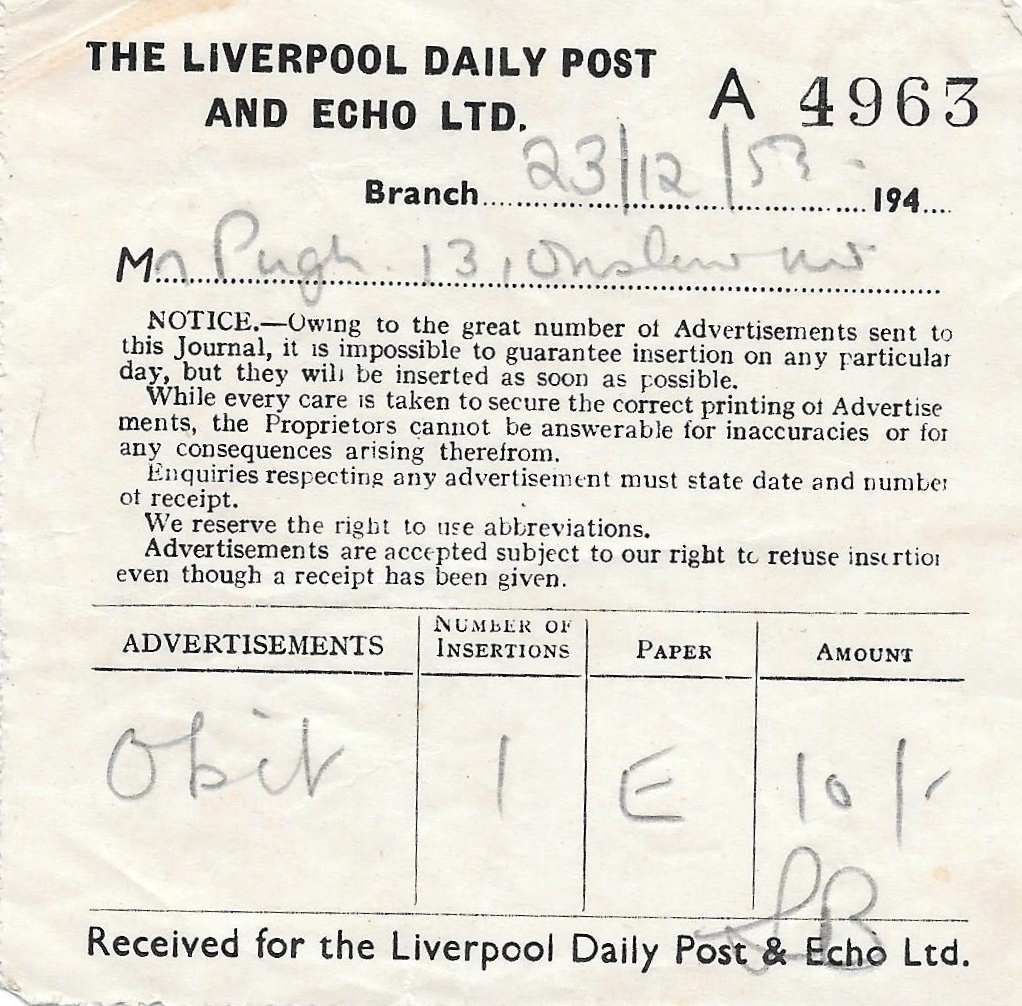

Charles died at home on Tuesday, 22 December 1953. The next day, Bessie placed a death notice in the Liverpool Echo, which appeared on Christmas Eve:

On the Wednesday, Bessie (Elizabeth Pugh) placed a noticed in Liverpool Echo costing 10 shillings which appeared on Thursday December 24th

“PUGH – Dec. 22, at his residence, Onslow Road, CHARLES, beloved husband of Elizabeth Pugh and dear father of Mabel, Ted and Winnie. Interment at Anfield Cemetery, on Saturday next, at 11.”

-

Despite Charles’s request for cremation, the notice states an interment (burial) at Anfield Cemetery. This suggests either the wishes were not followed due to logistics, family preferences, or custom.

-

The cost—10 shillings—indicates the importance of public memorialisation and respectability.

5. Surviving Artefacts: Notebook and Ephemera

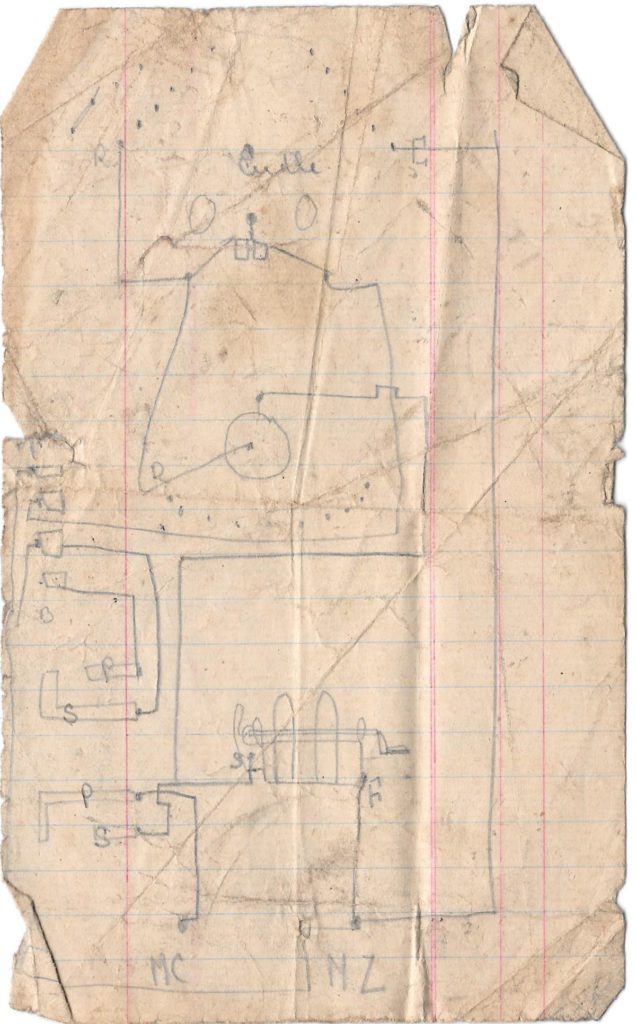

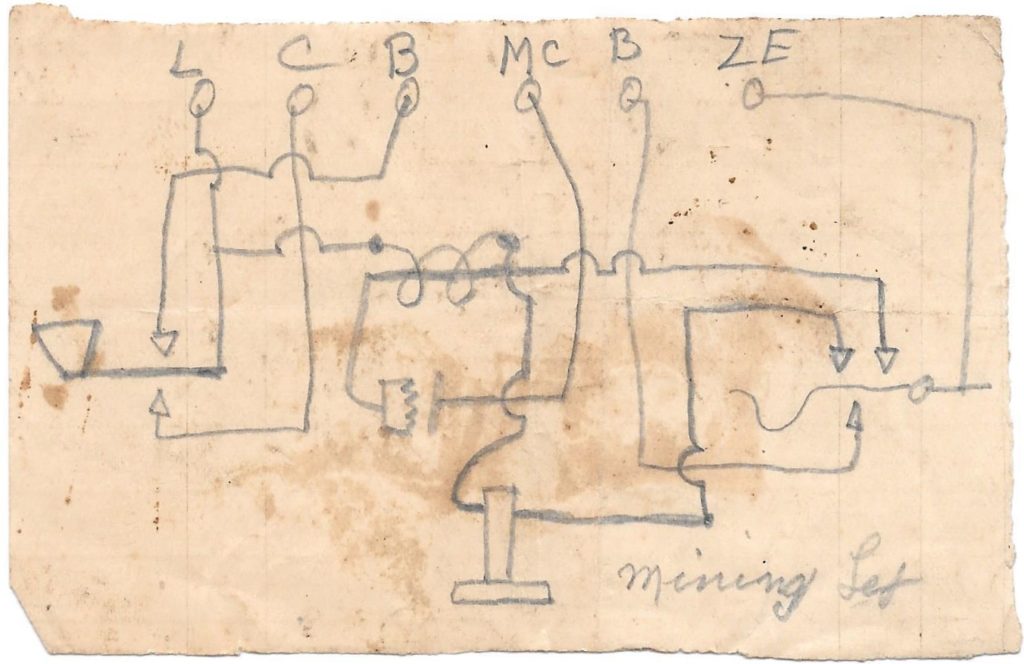

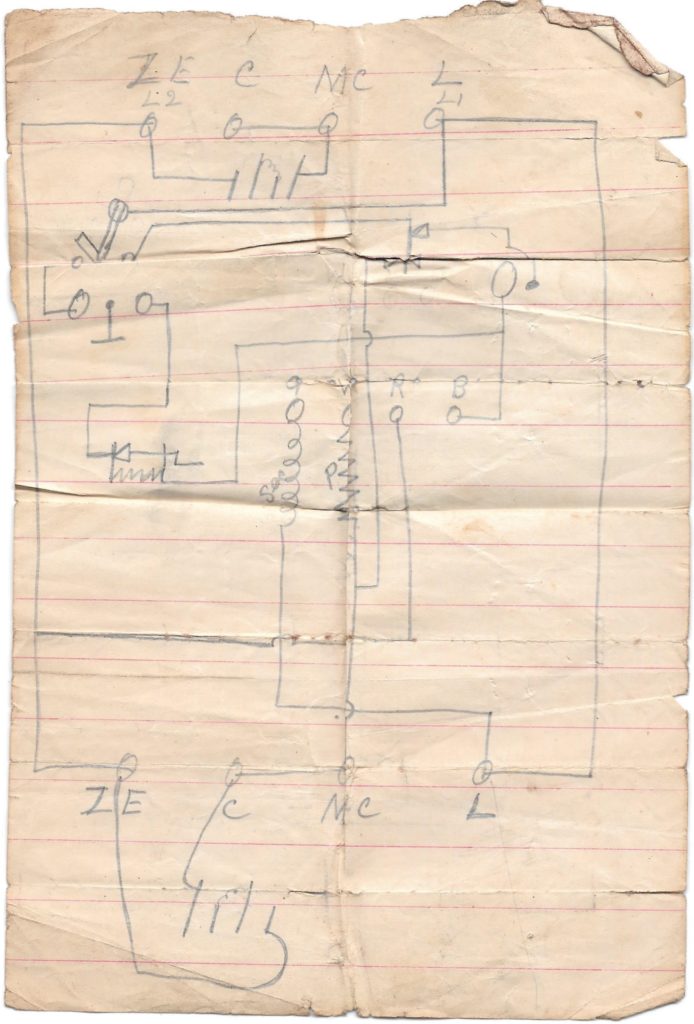

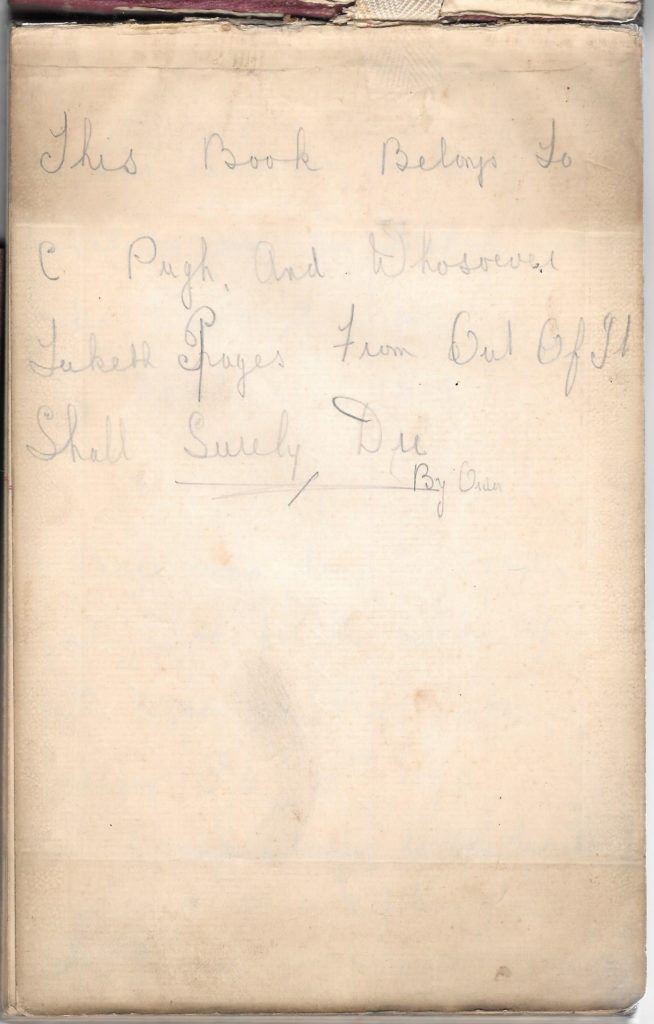

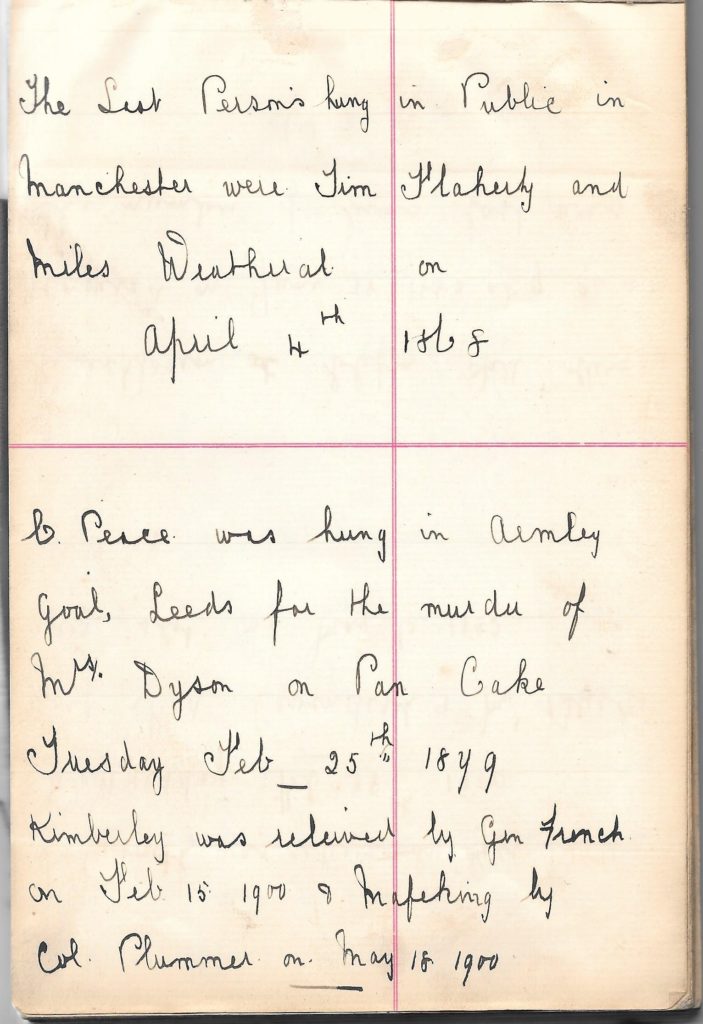

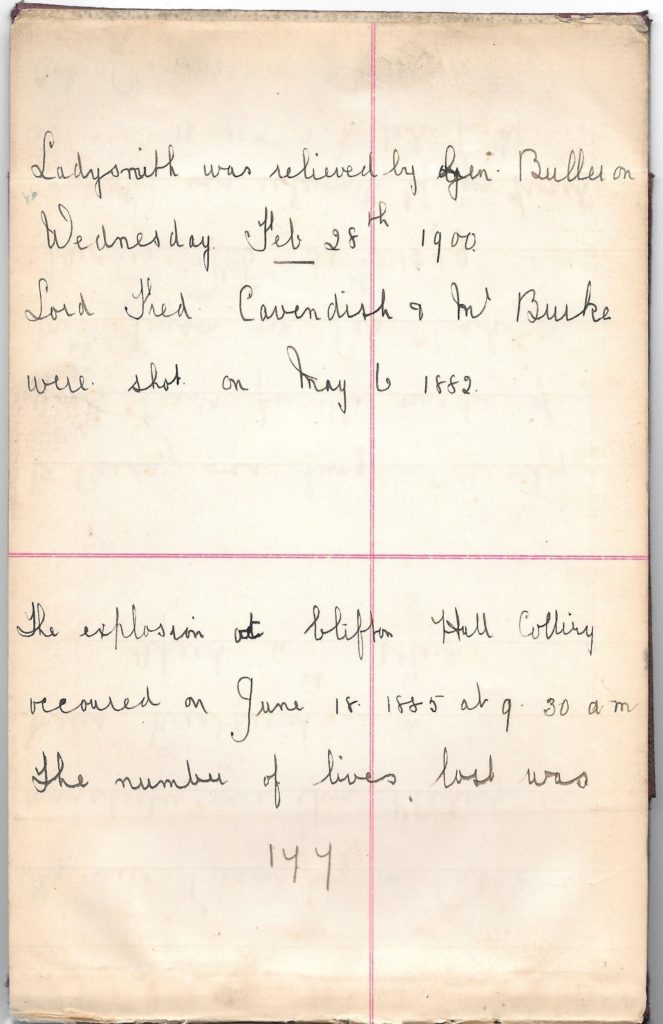

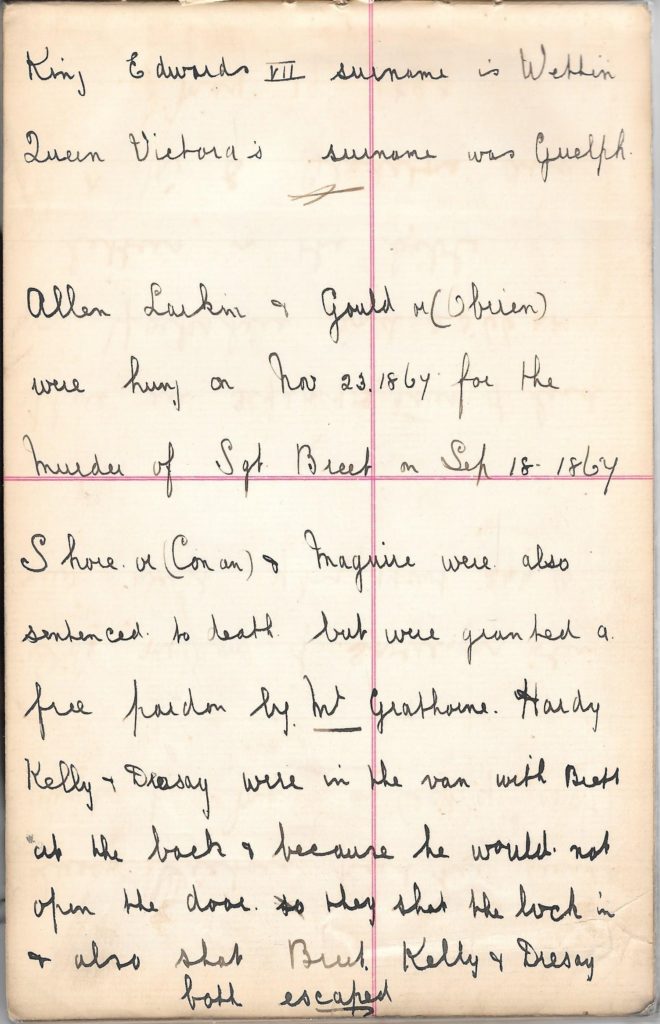

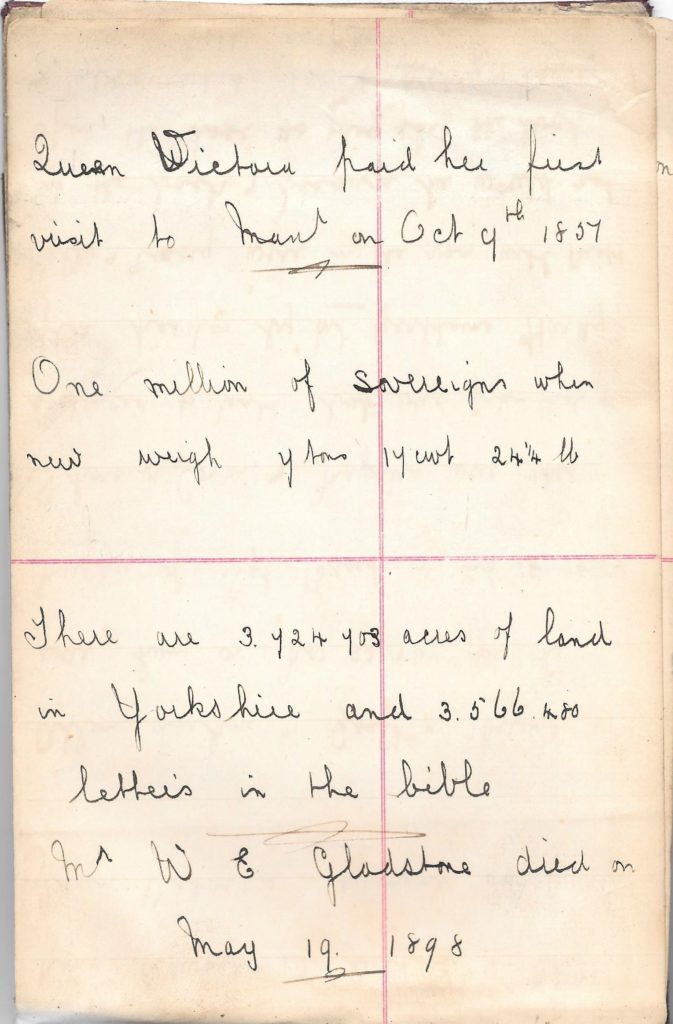

I mention the acquisition and digitisation of Charles’s notebook and various pieces of ephemera in 2010. Such personal artefacts are invaluable for family and local historians:

I mention the acquisition and digitisation of Charles’s notebook and various pieces of ephemera in 2010. Such personal artefacts are invaluable for family and local historians:

-

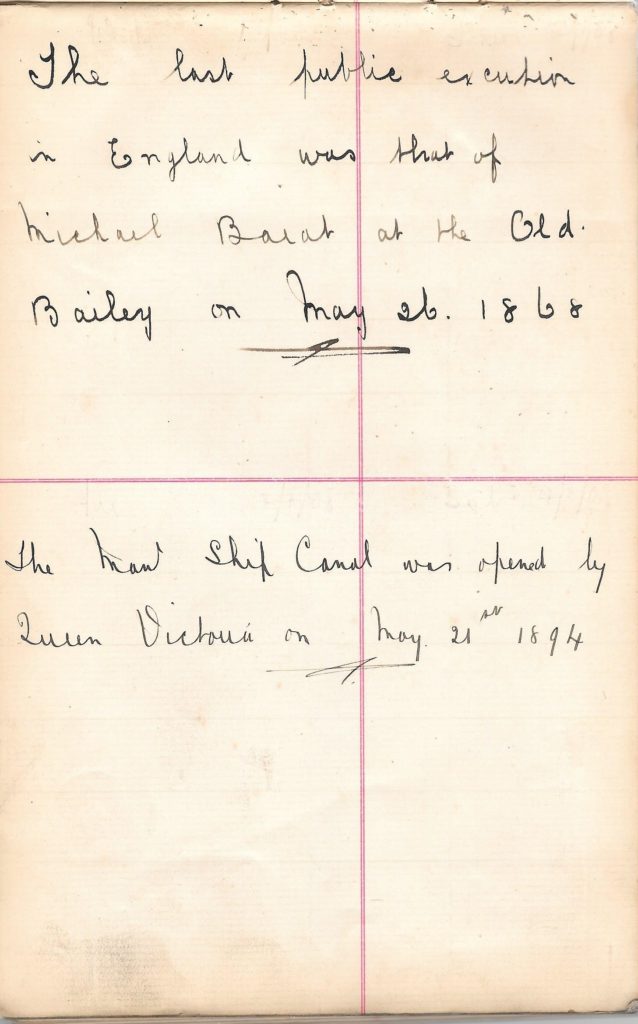

The notebook likely contains not only personal reflections but practical notes—possibly relating to his work, financial records, or observations about daily life.

-

Ephemera may include company documentation, ration books, club membership cards, or correspondence.

6. Interpretation: Social and Emotional Meaning

Charles Pugh’s story is emblematic of a generation:

-

Skilled Working Class: His career in telecommunications positioned him within a modern, technically skilled class, vital to Britain’s economic and technological progress.

-

Stability and Modesty: The “happy & not eventful life” he describes is a testament to the quiet dignity, endurance, and values of his generation—work, family, respectability, and order.

-

Emotional Reserve: The letter, while affectionate, is composed and restrained. Even his wish to spare women from the funeral hints at a stoic, self-effacing masculinity common in early 20th-century Britain.

-

Transition and Change: His career spanned the switch from Victorian manual work to modern technological industry; his lifespan encapsulates the movement from Empire to Welfare State.

7. Legacy and Historical Value

-

Family Memory: Through Bessie’s longevity (living until 1988), the memory of Charles’s life and values persisted into the late 20th century.

-

Archival Significance: His notebook, last letter, and related documents are of great value not only to descendants but to social historians, illustrating the lived experience of ordinary people in 20th-century Britain.

-

Digital Preservation: By digitising and sharing these materials, I ensure the preservation of a unique, personal perspective on British social history.

Conclusion

Charles Pugh’s life, as reconstructed through records, family memory, and surviving documents, tells a story of quiet resilience, technical skill, domestic affection, and modest legacy. The artefacts—his letter, notebook, and the public notice—capture the intersection of the personal and the historical at a time when Britain was transforming rapidly. They are precious fragments of working-class life and are part of the rich tapestry of British history.

On the 21st July 2010, I acquired his notebook and have digitised it’s contents with various pieces of ephemera.