On Saturday, 19th September 1908, a seventeen-year-old young woman named Emily Rourke, living in Leeds, embarked on a personal and creative project that would come to serve as a cherished window into the social world of Edwardian England. She began an art album—a popular pastime of the era—inviting friends, classmates, and acquaintances to contribute drawings, poems, and personal reflections.

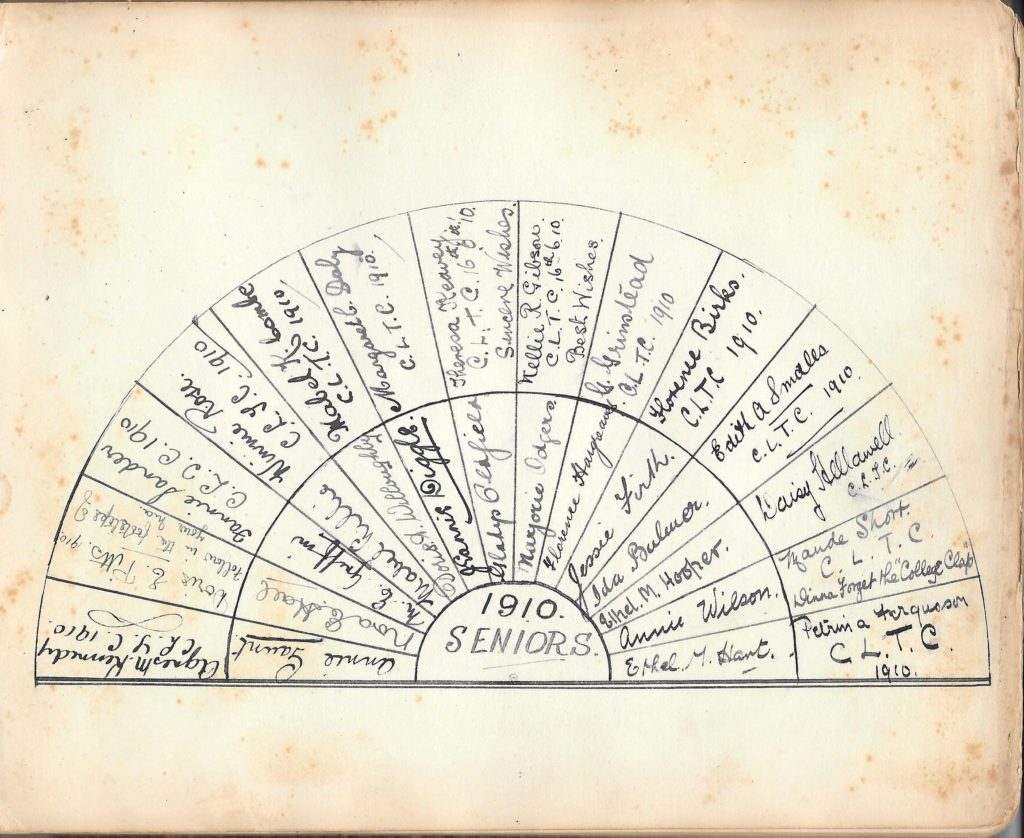

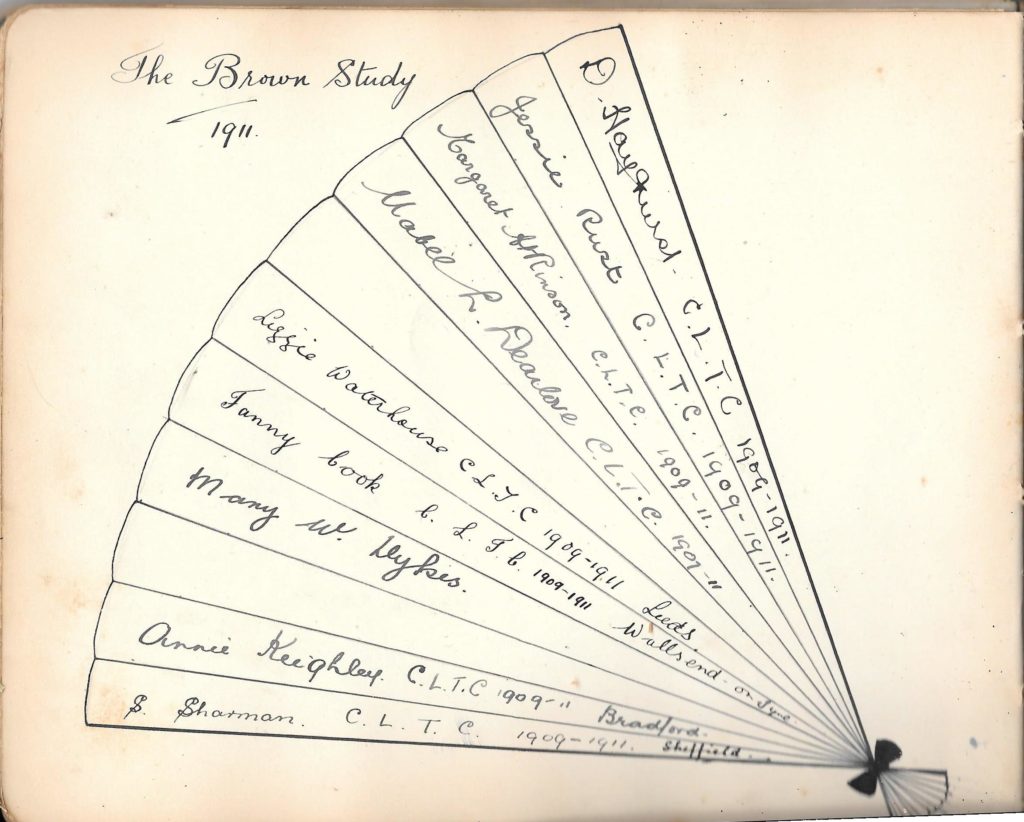

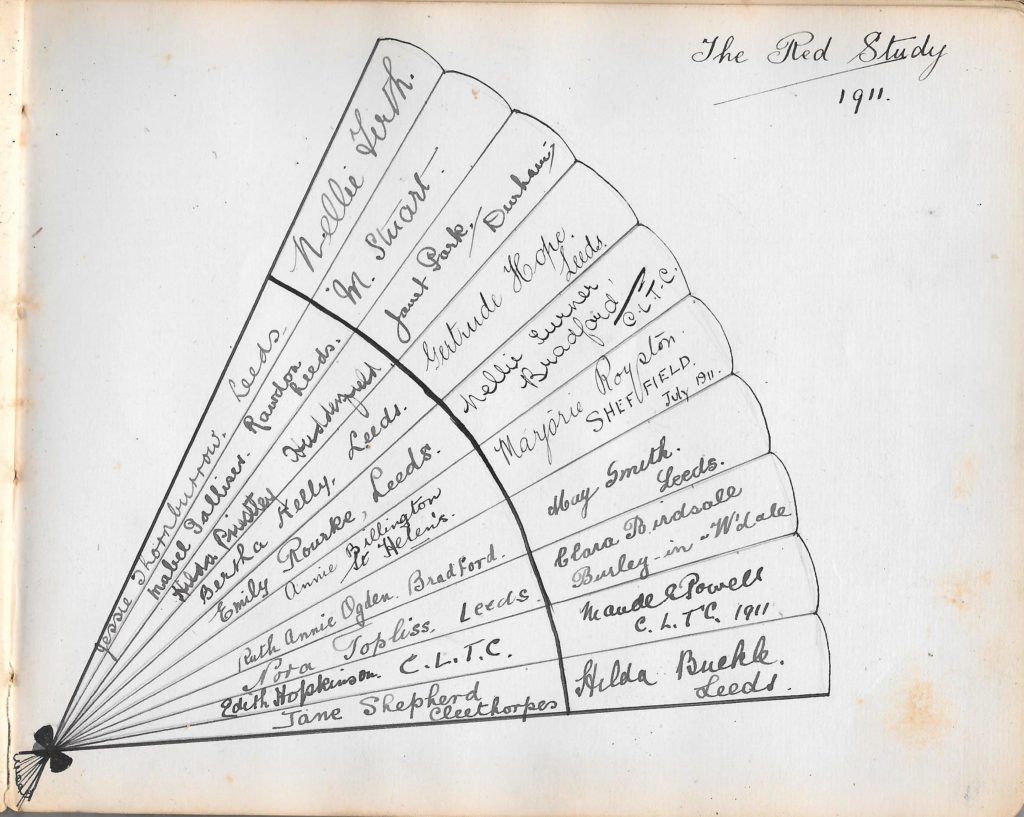

At the time, Emily was training to become a teacher at a college in Leeds. This period of her life is well documented, as she appears on the 1911 census alongside many of her contemporaries. Several of the names found within the album correspond with those listed on the same college census return, suggesting a close-knit community of aspiring educators who supported each other’s ambitions and friendships.

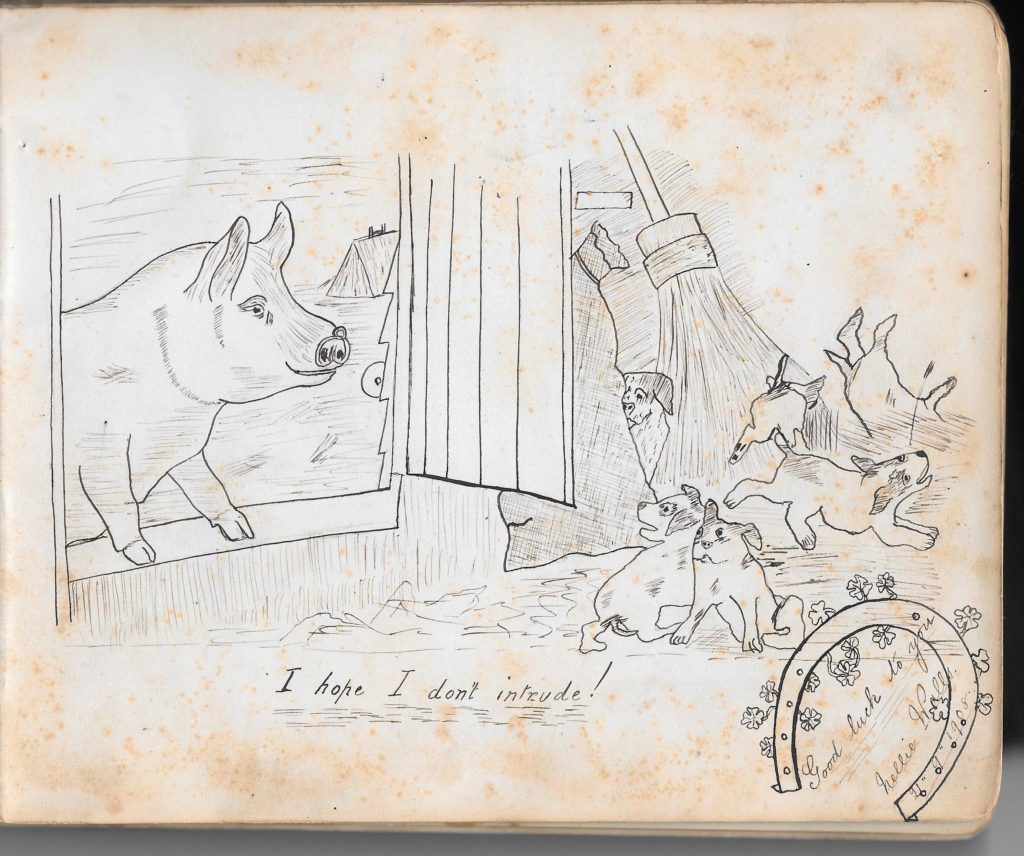

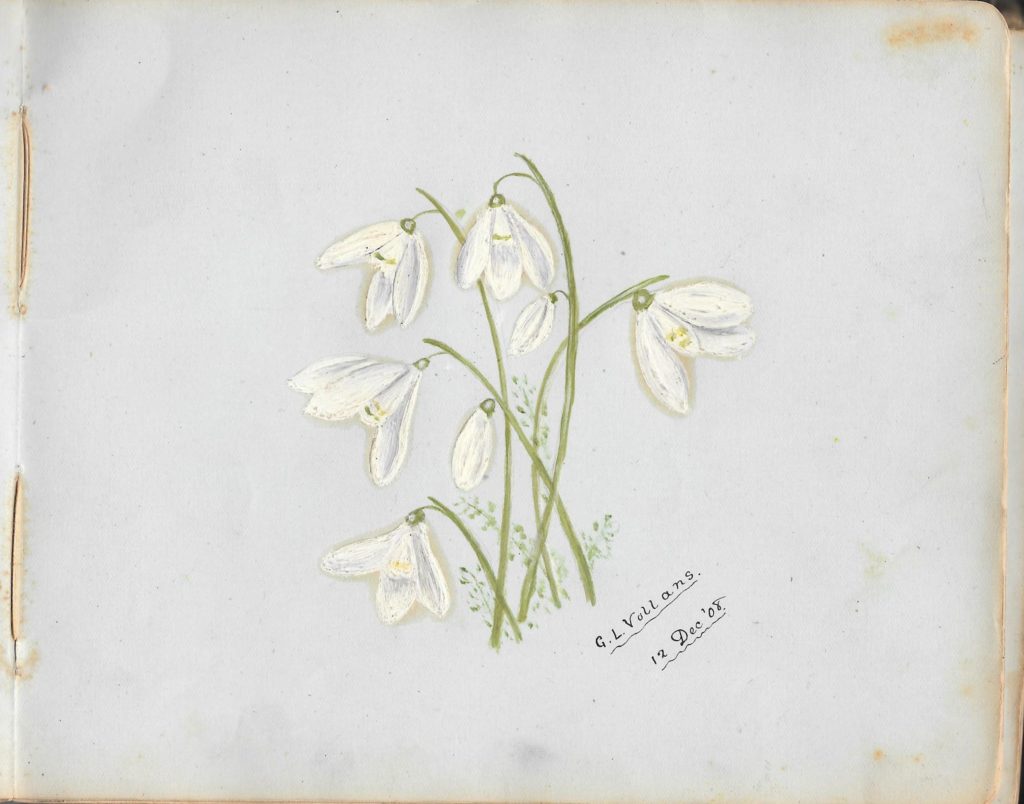

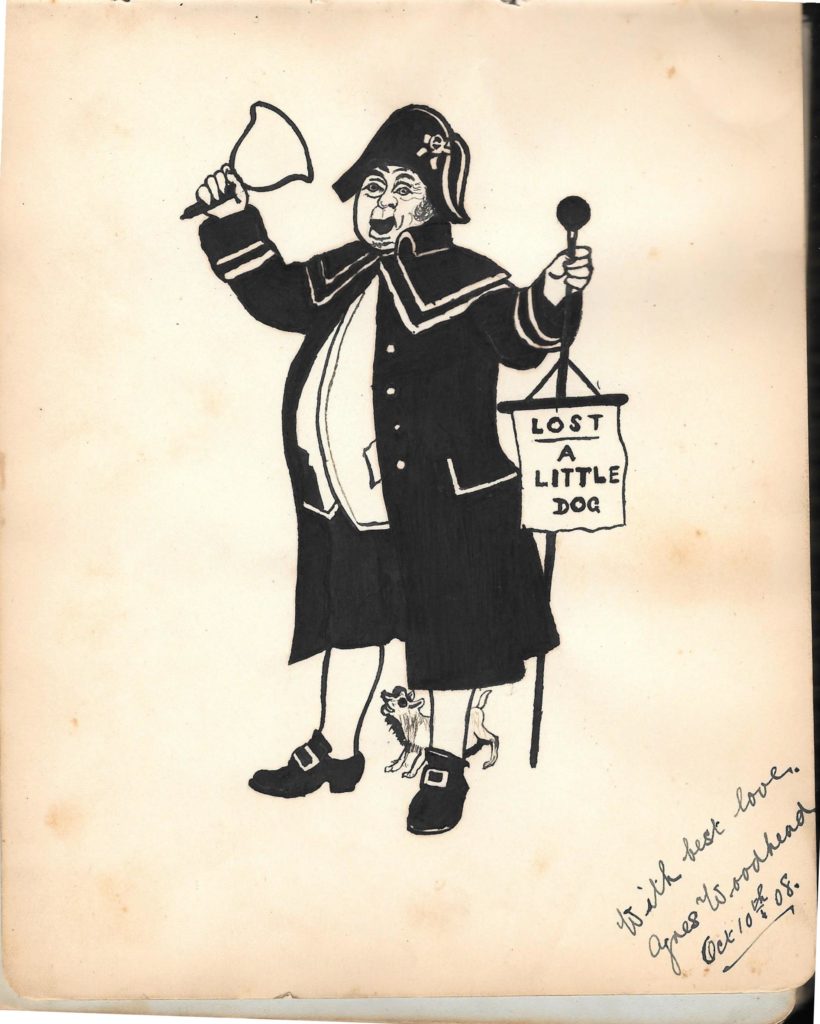

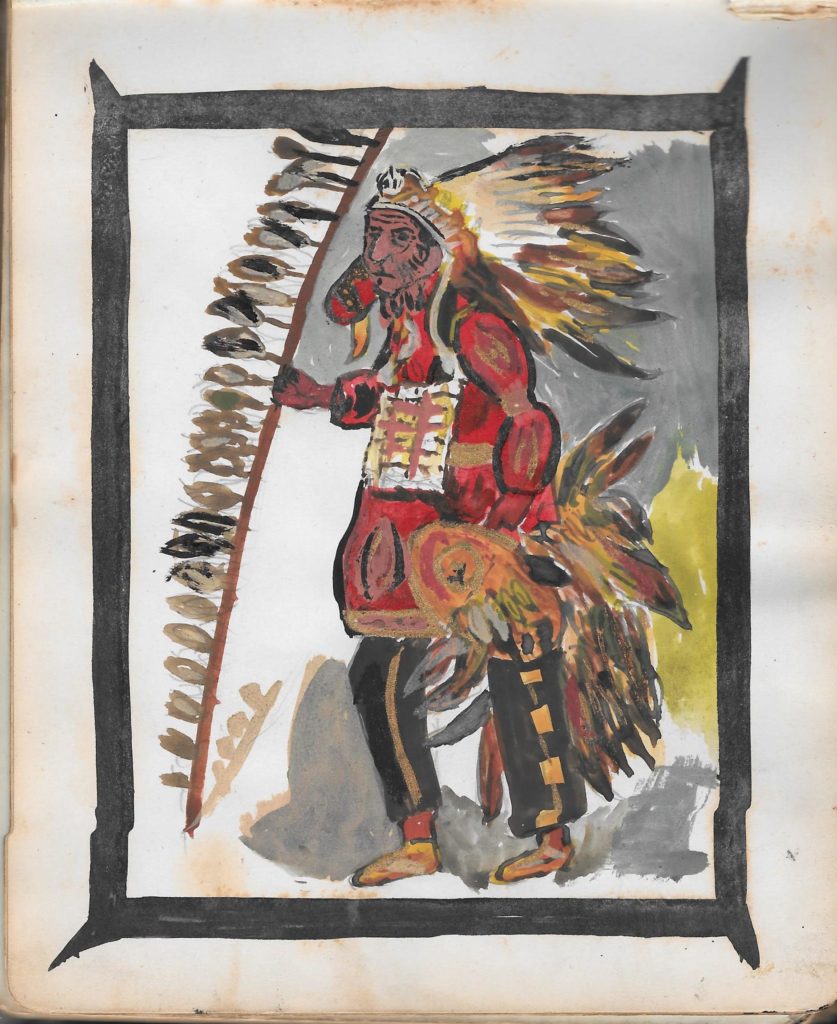

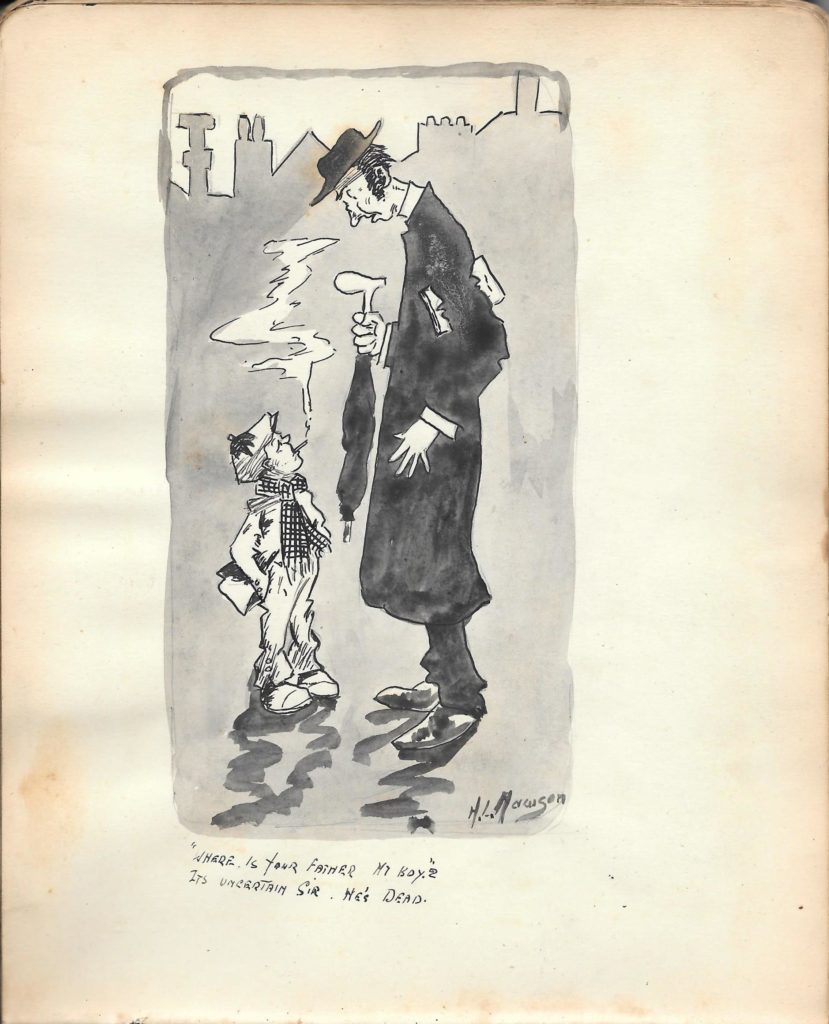

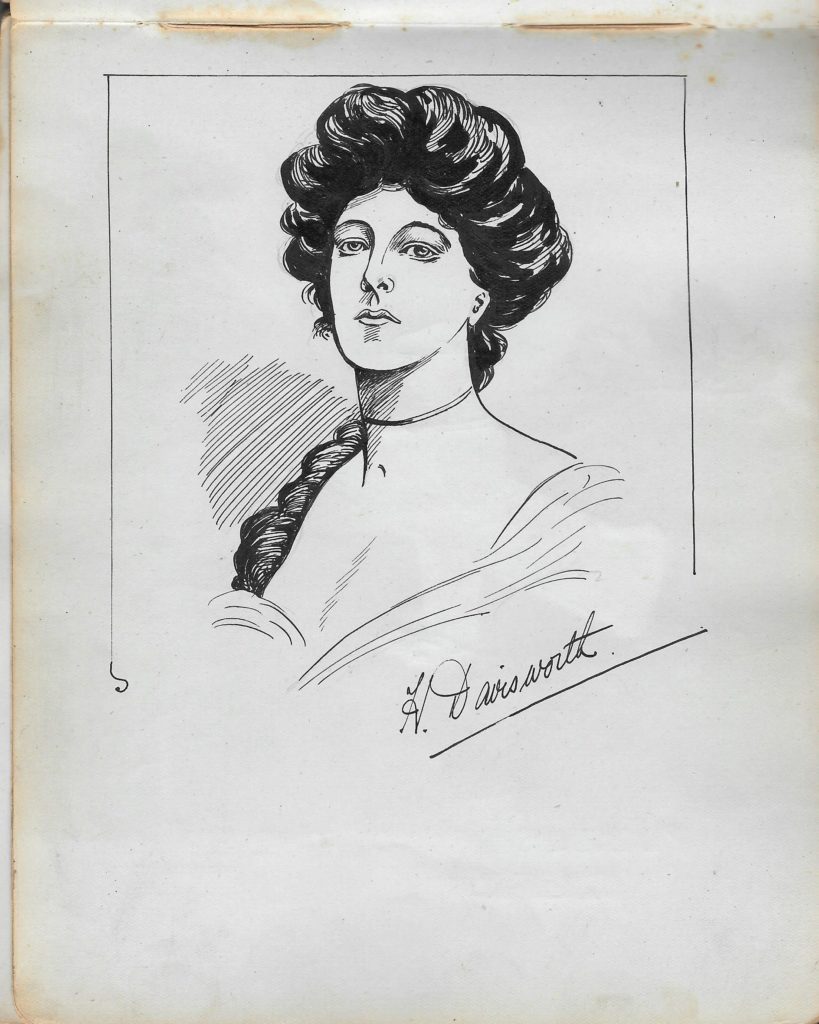

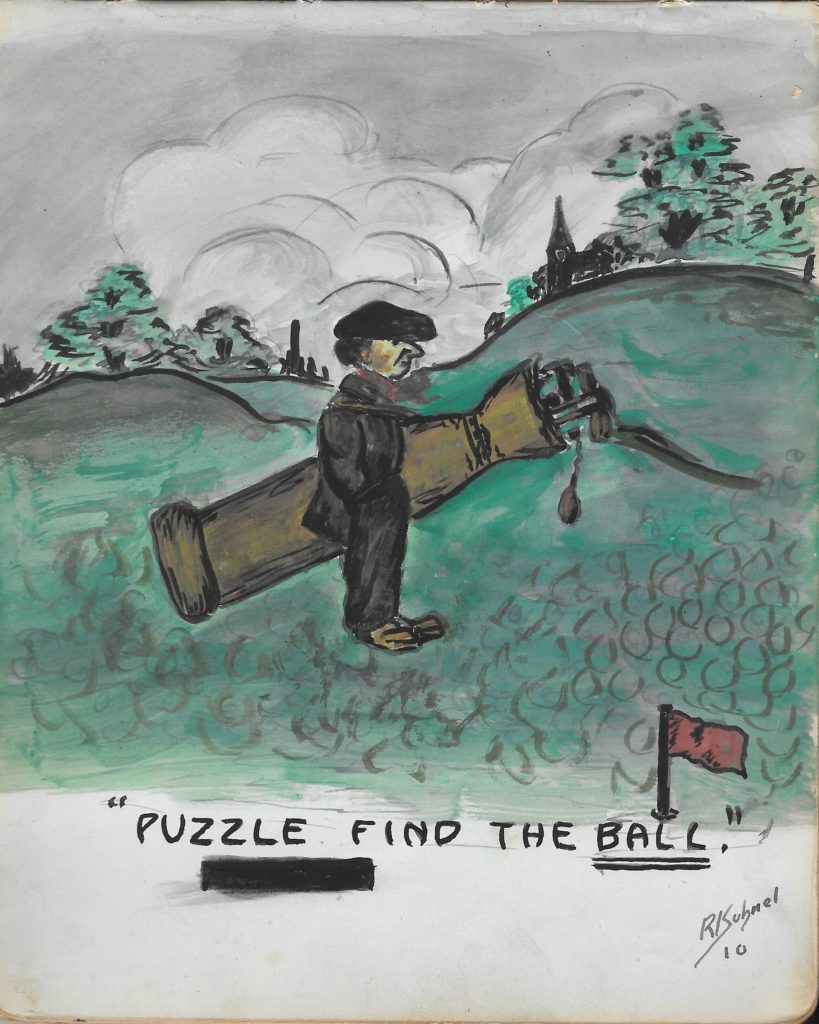

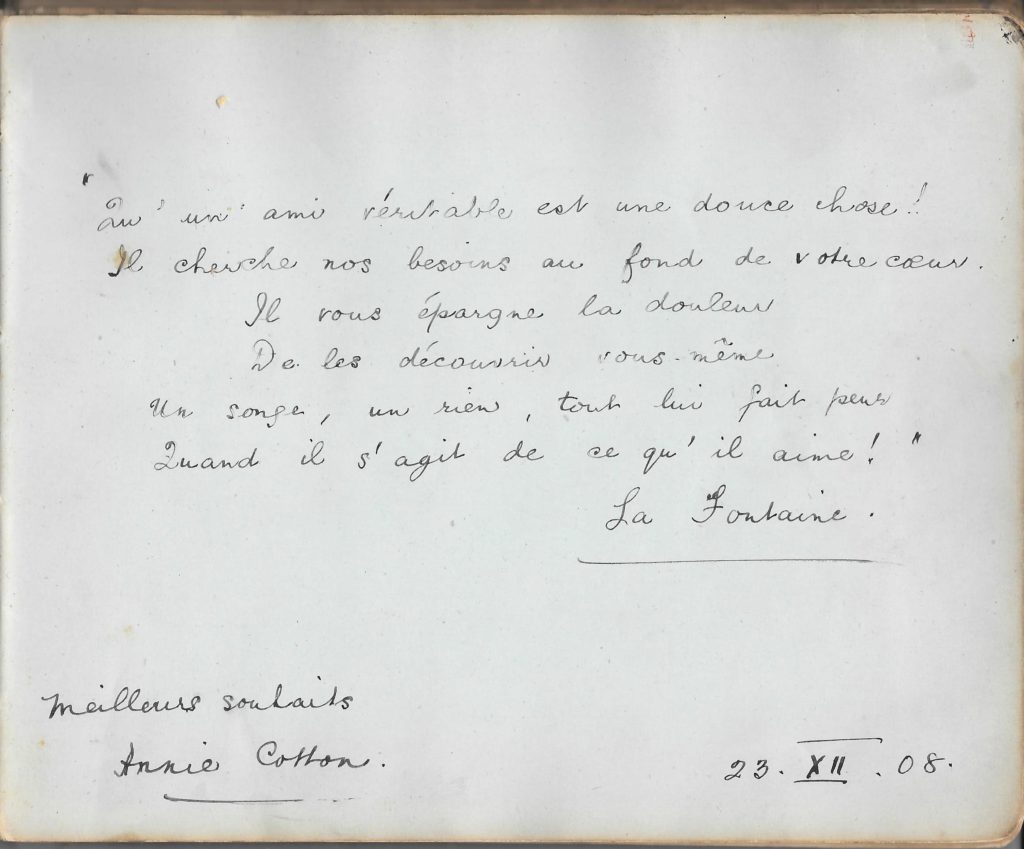

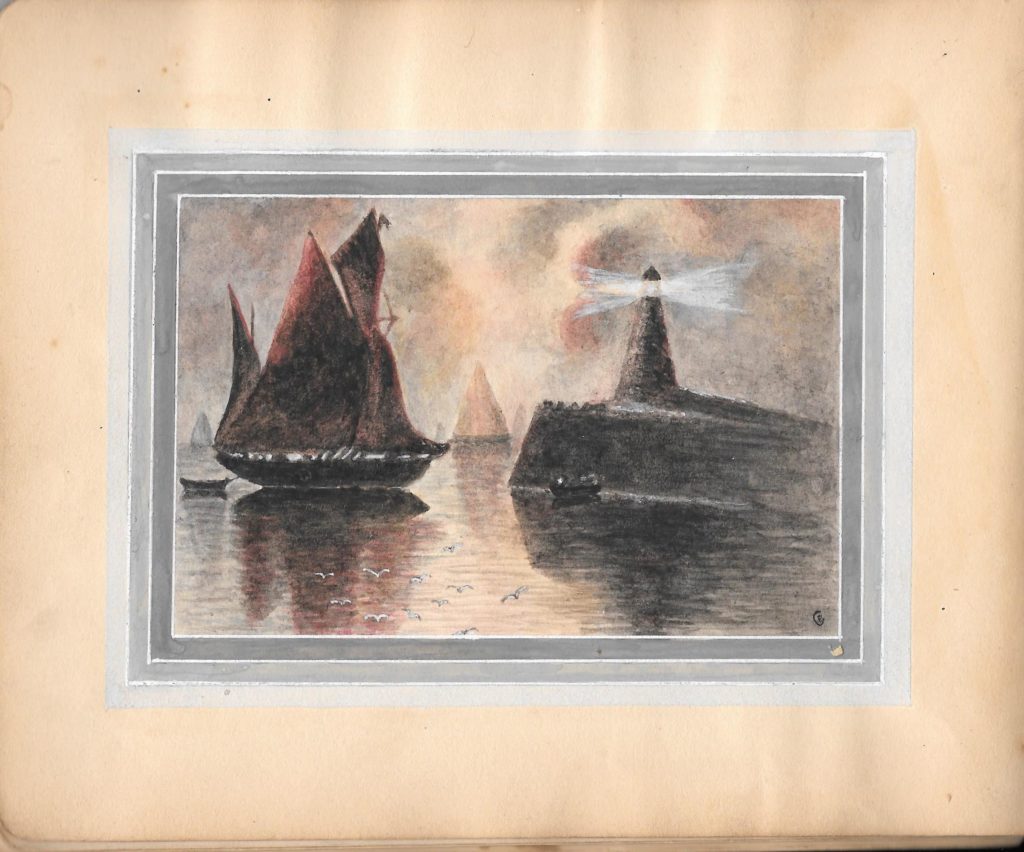

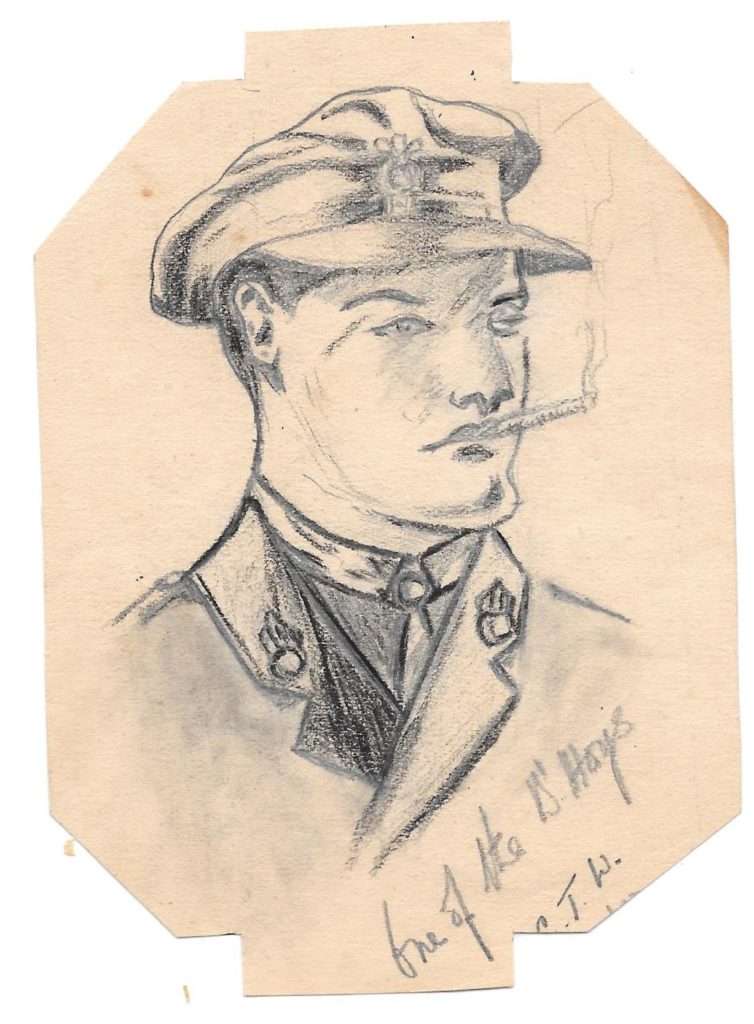

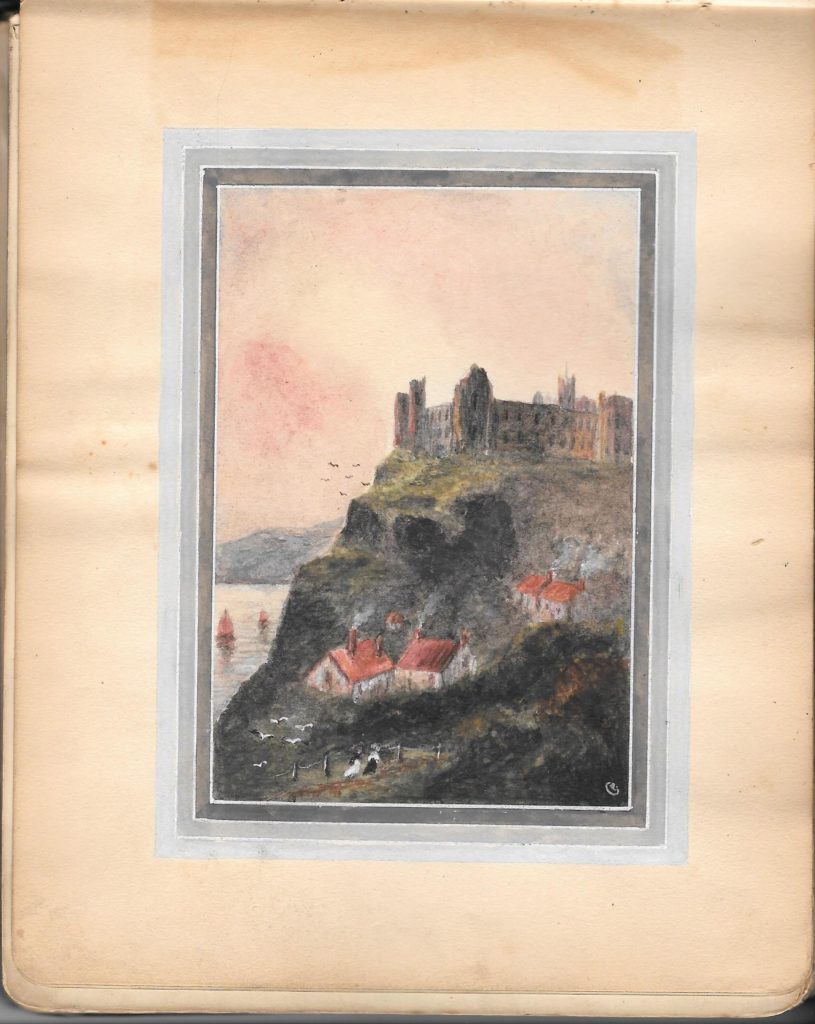

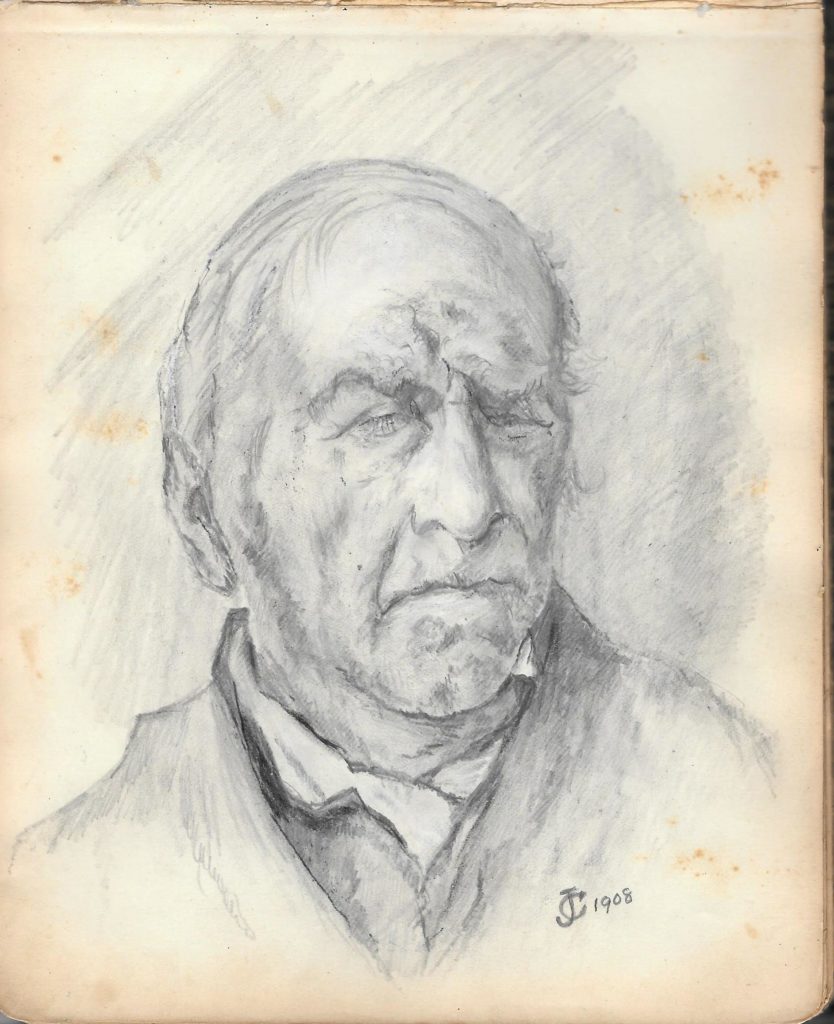

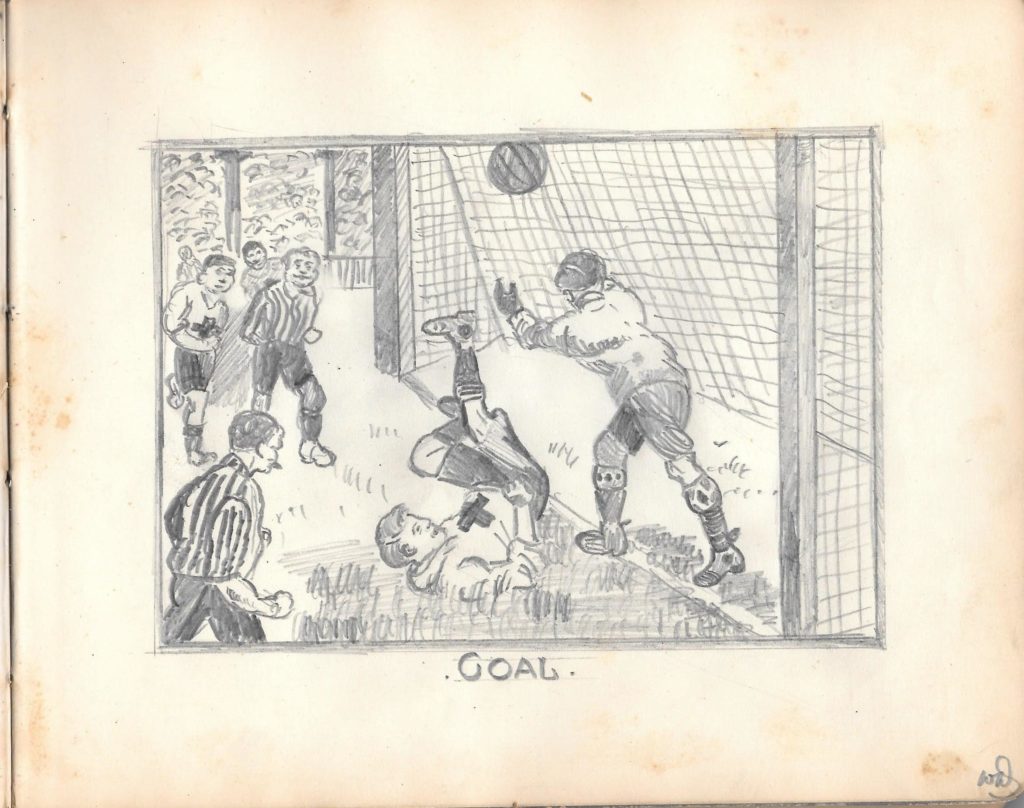

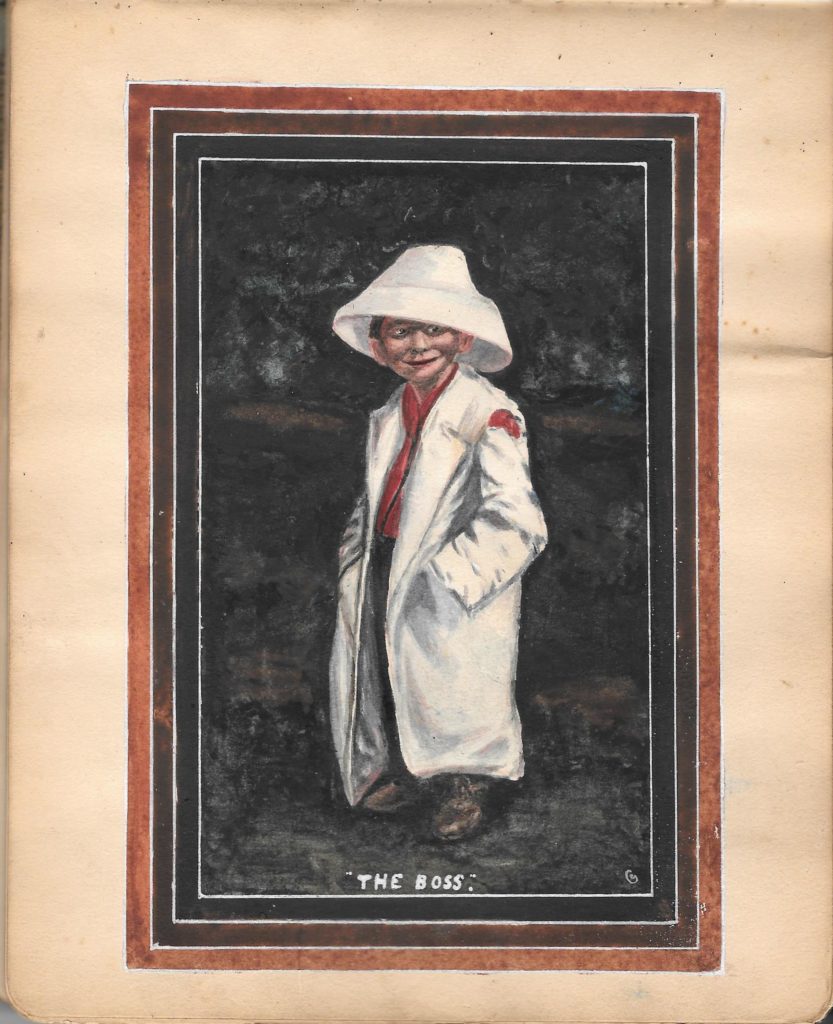

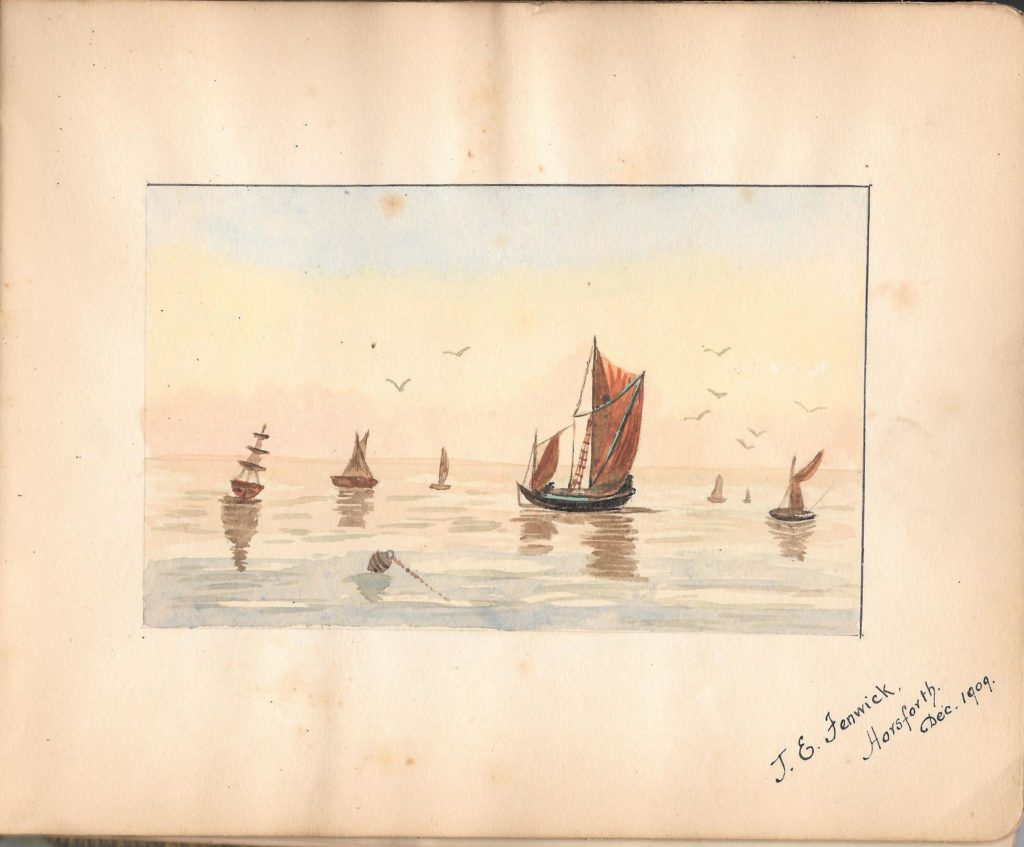

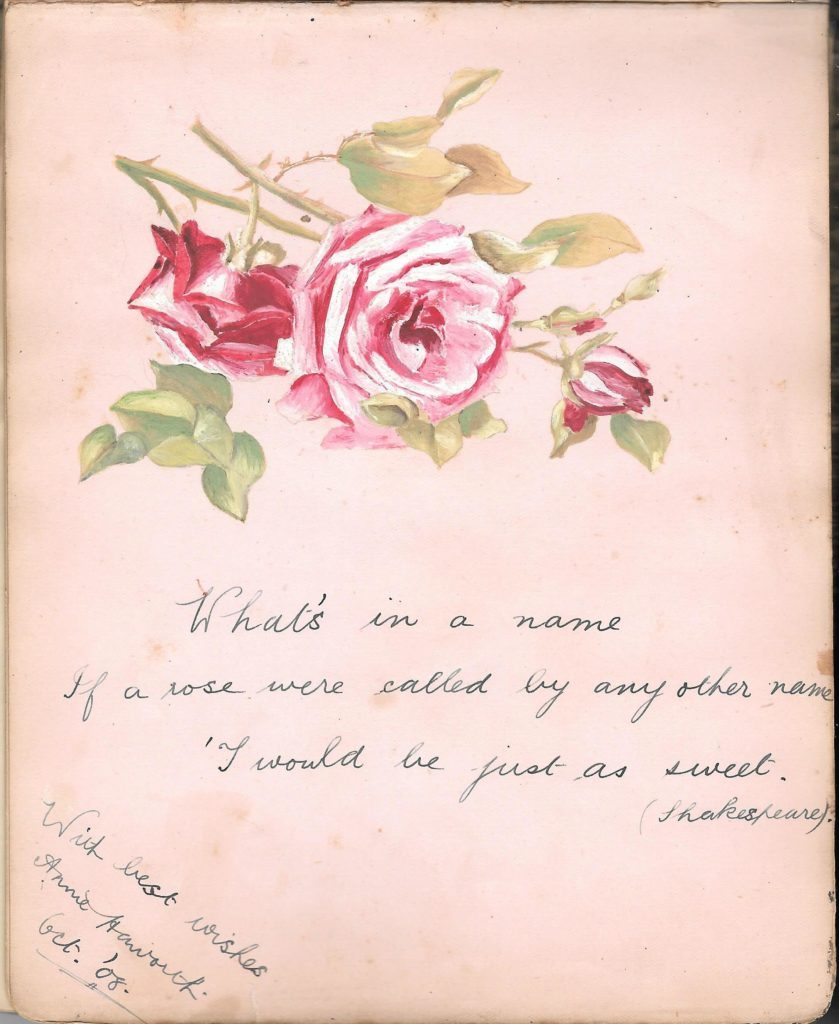

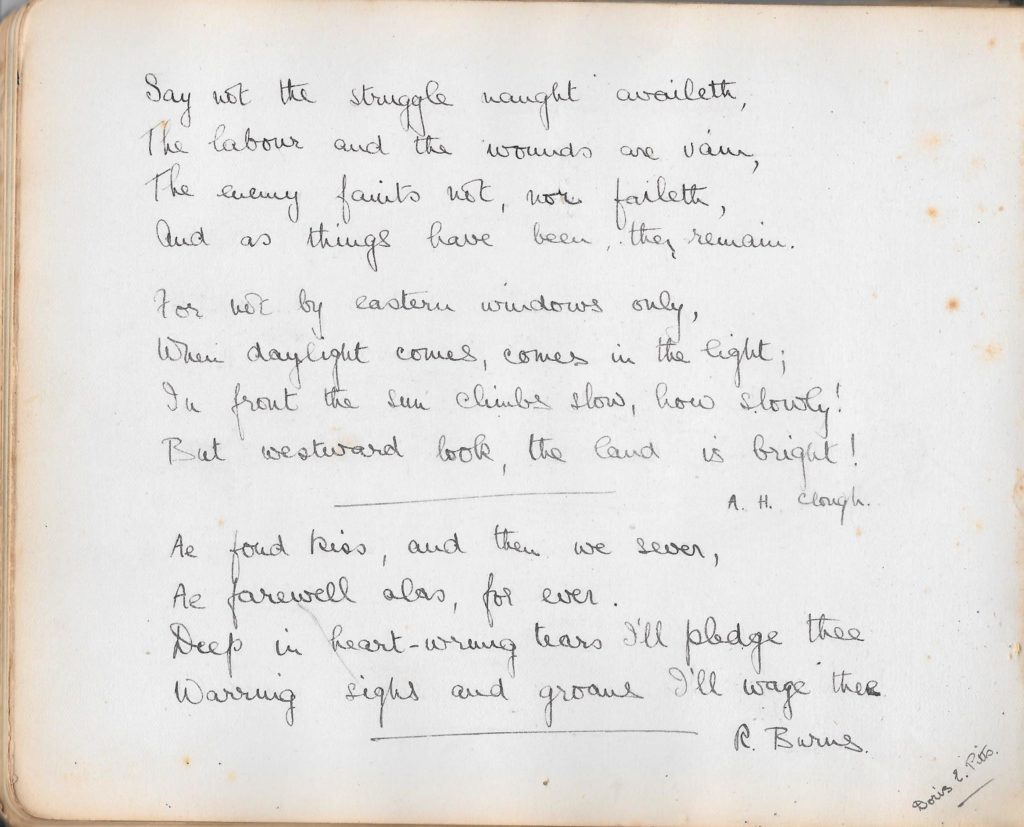

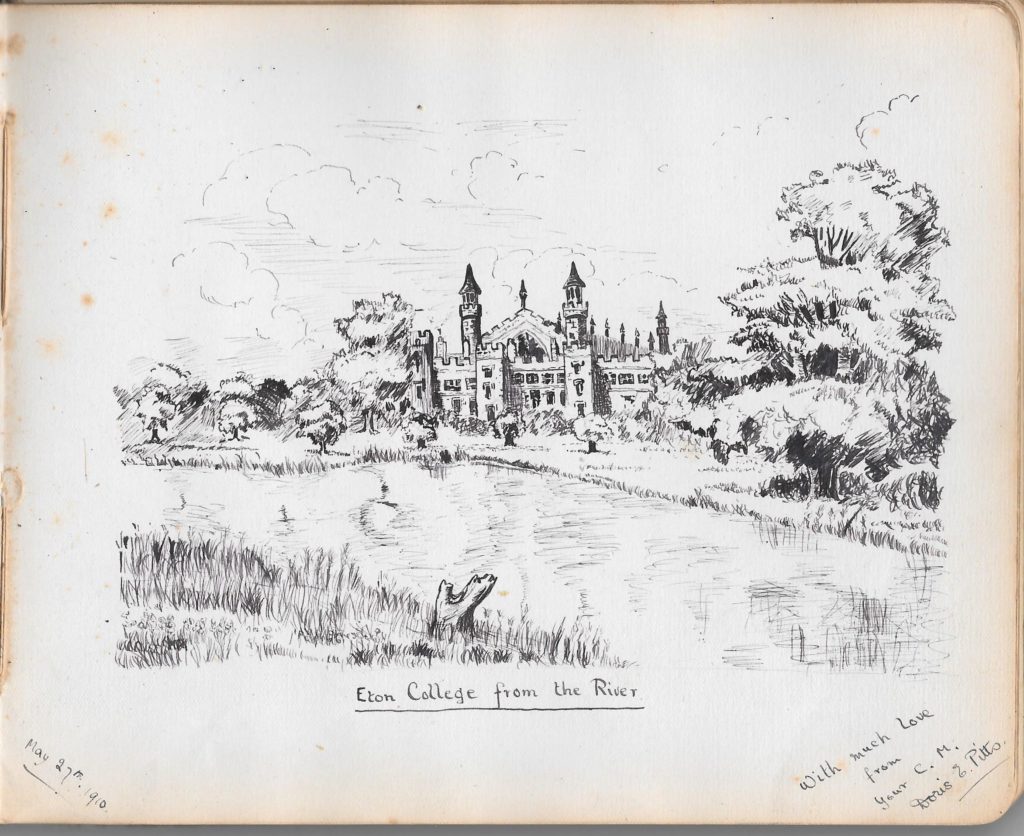

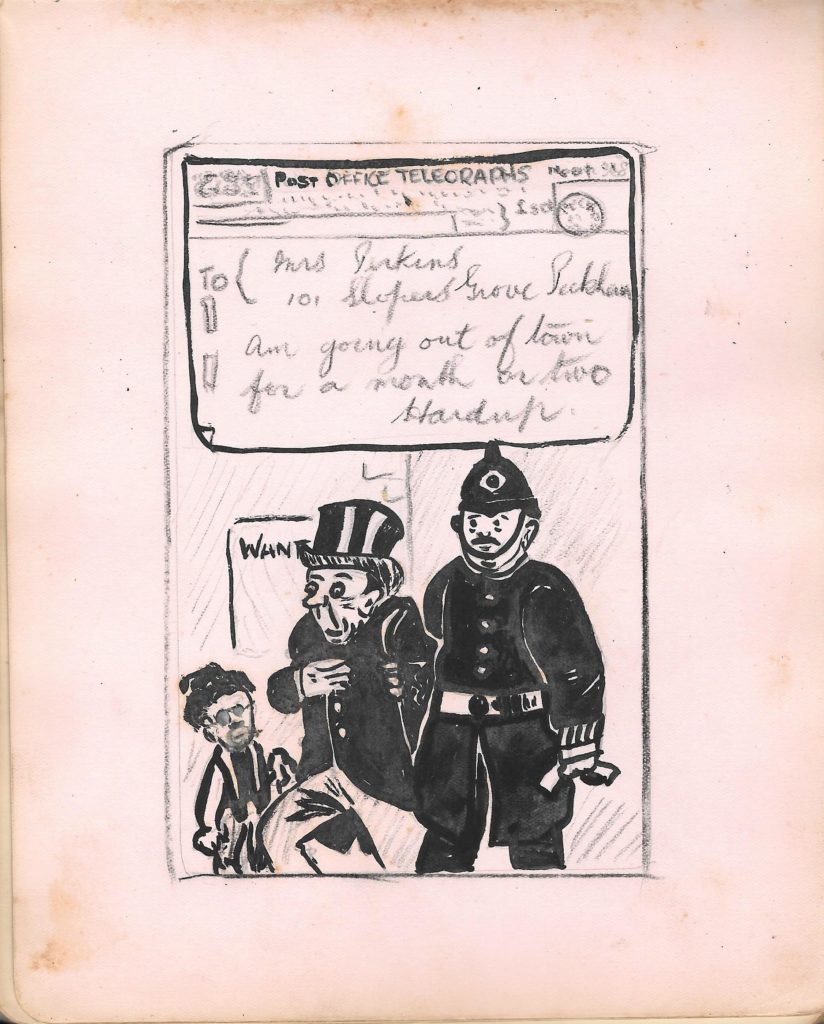

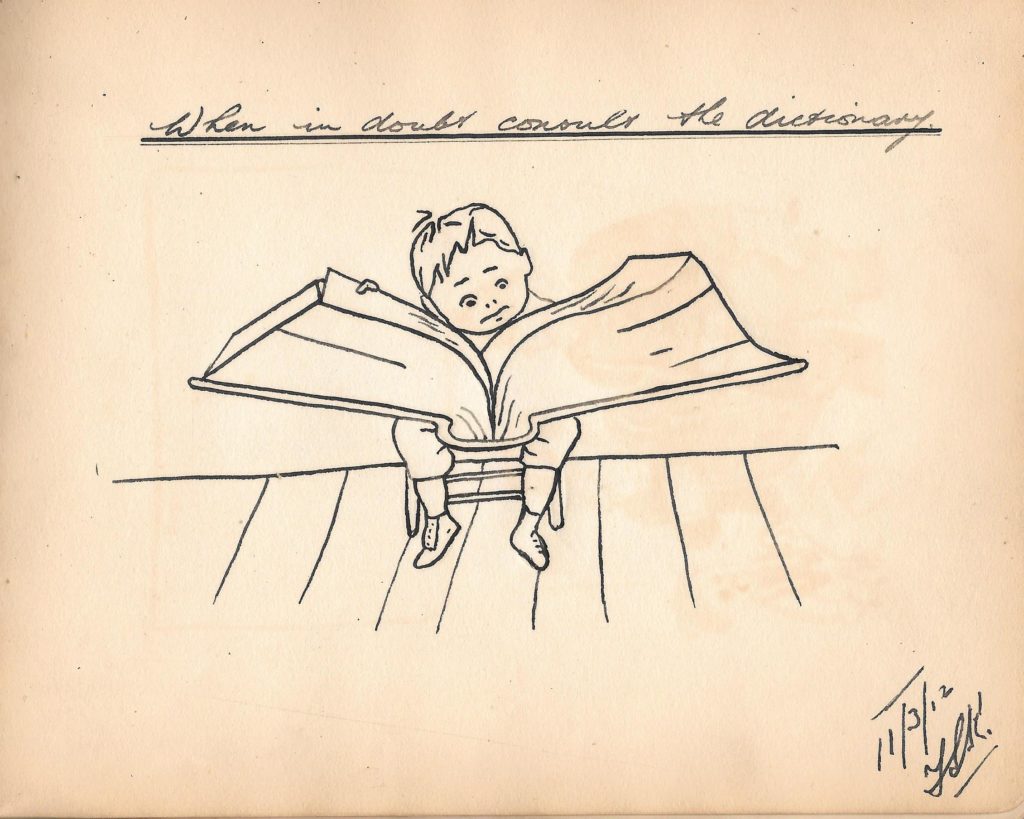

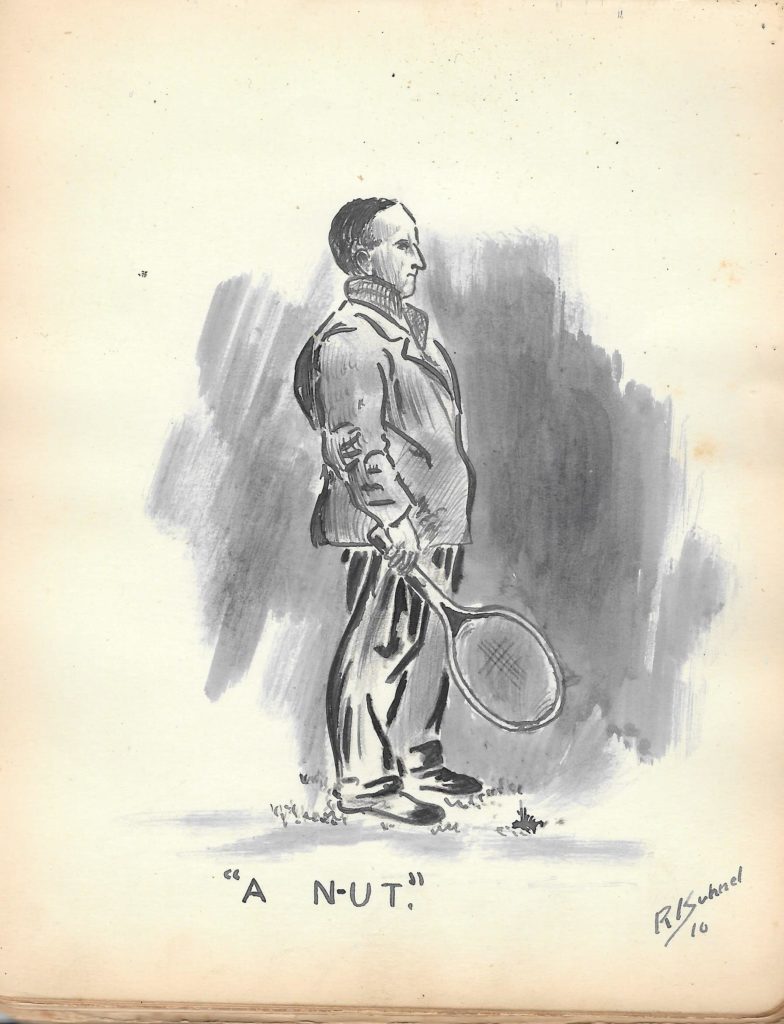

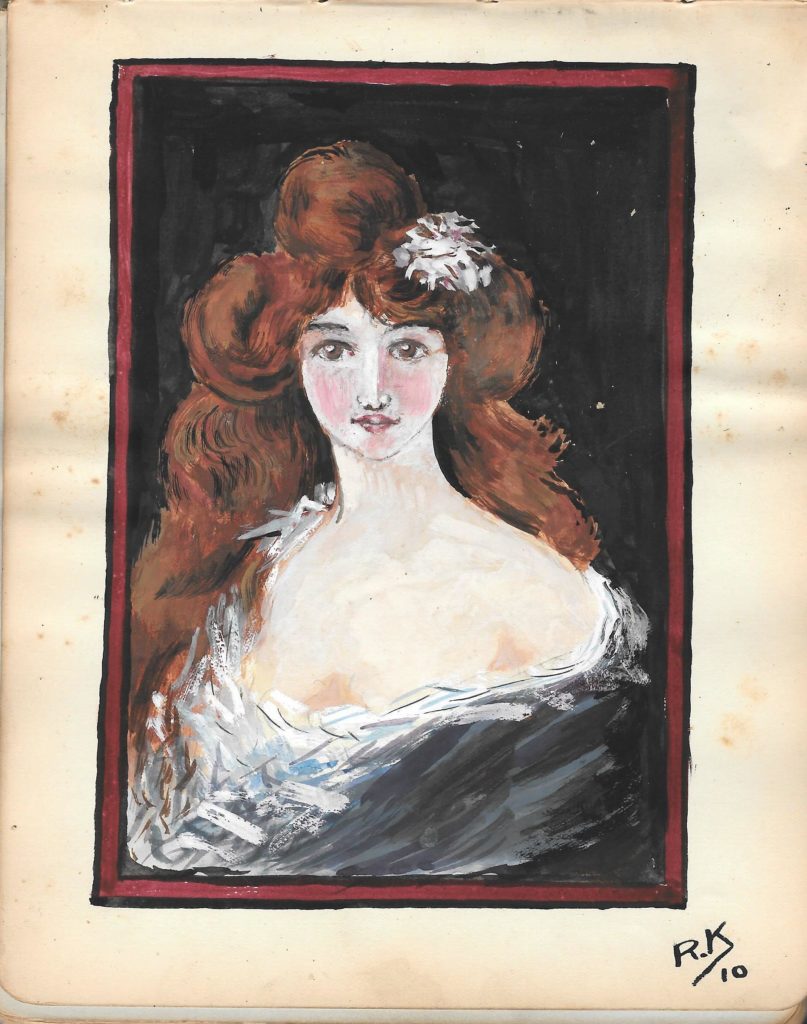

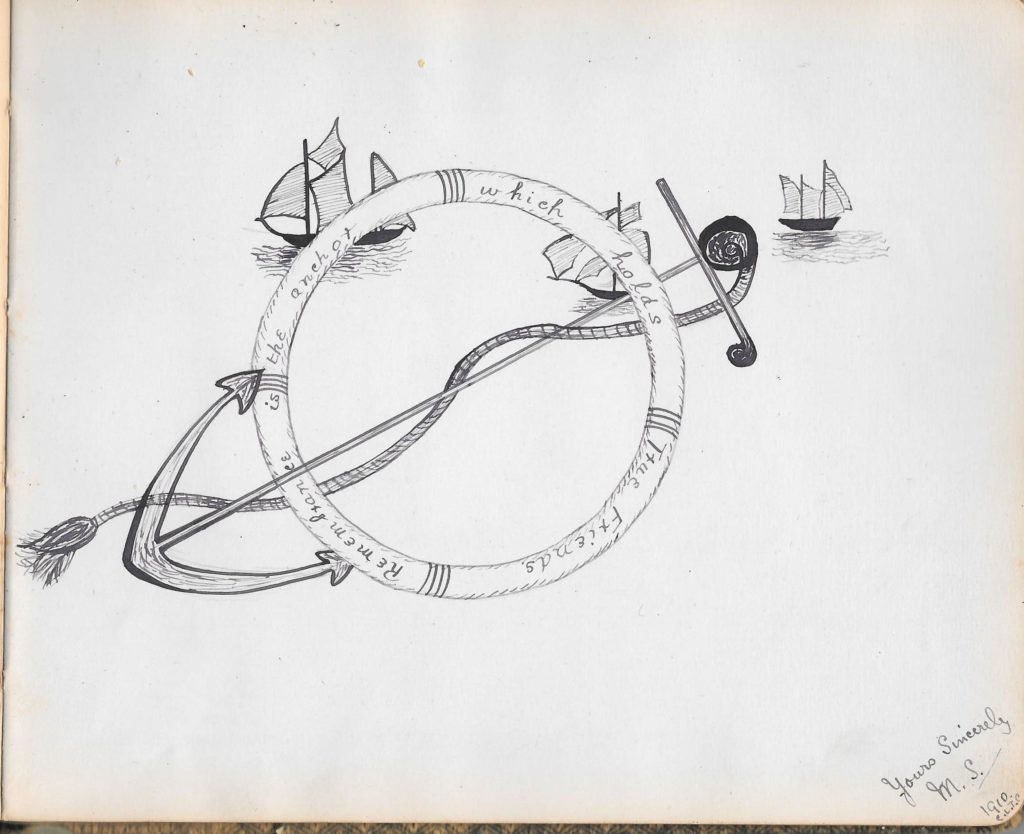

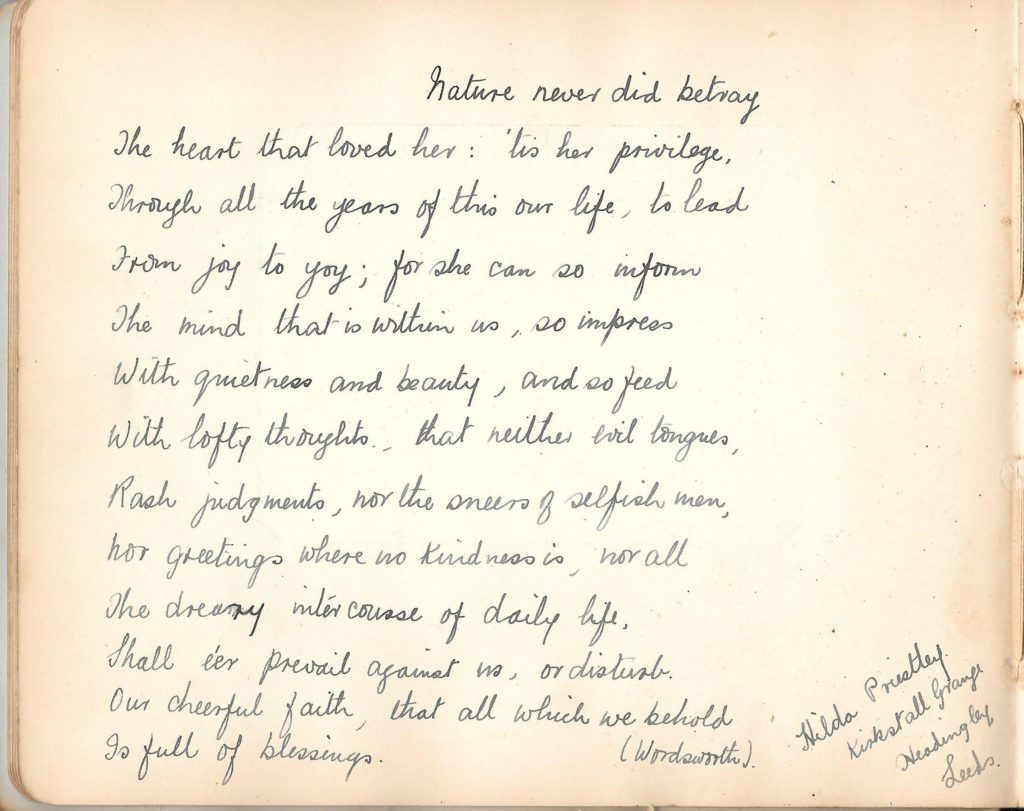

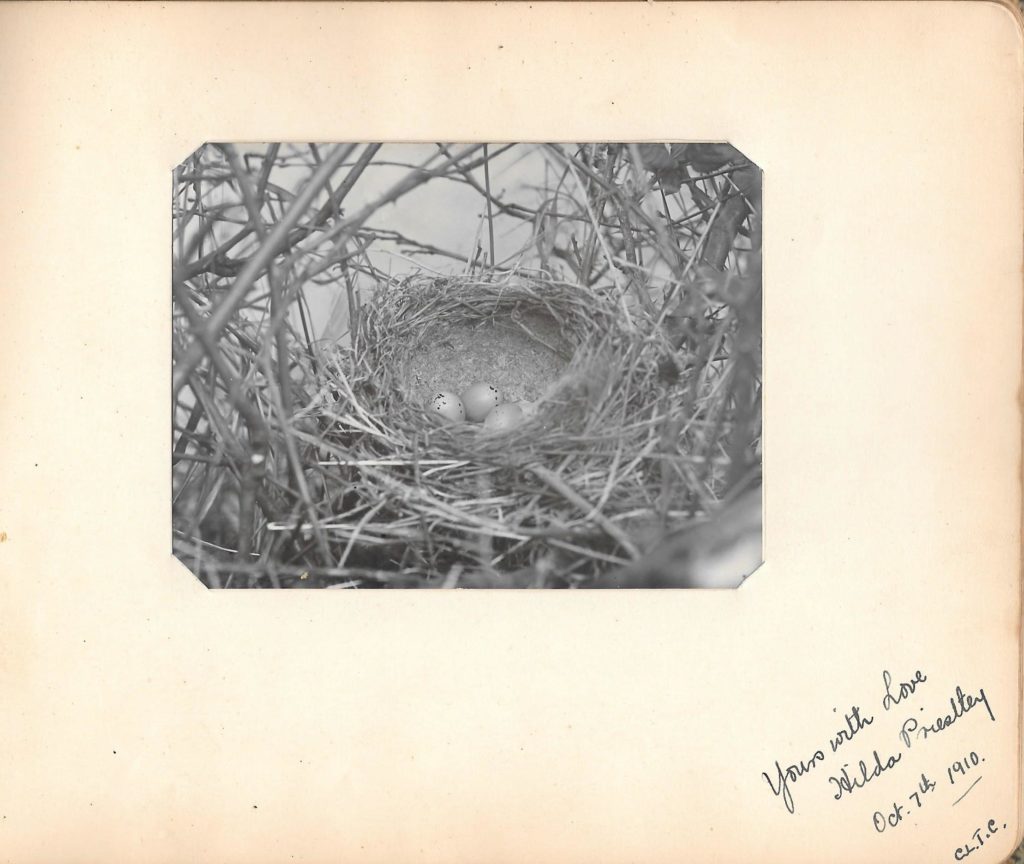

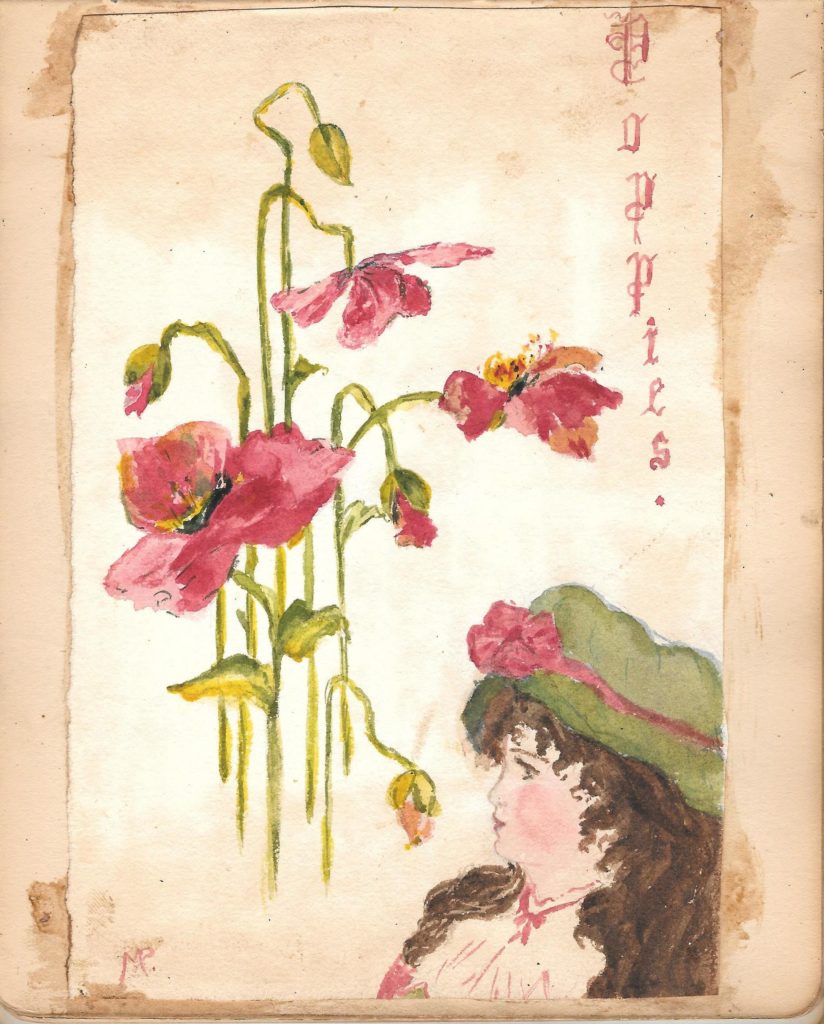

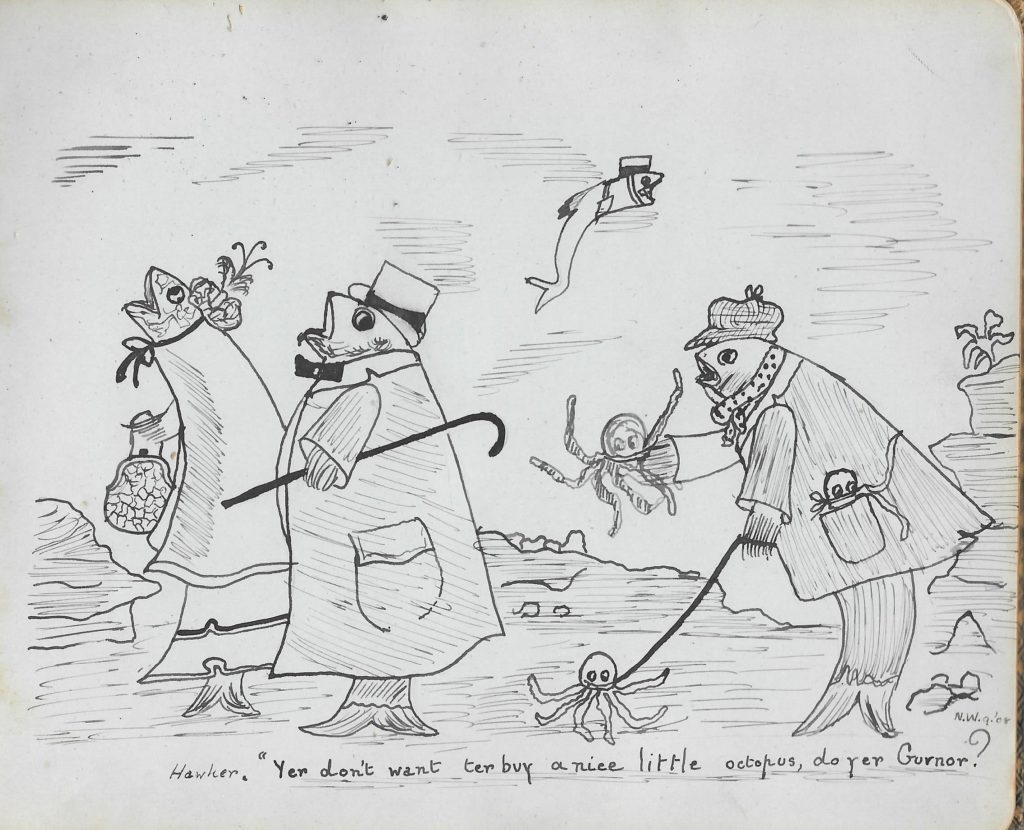

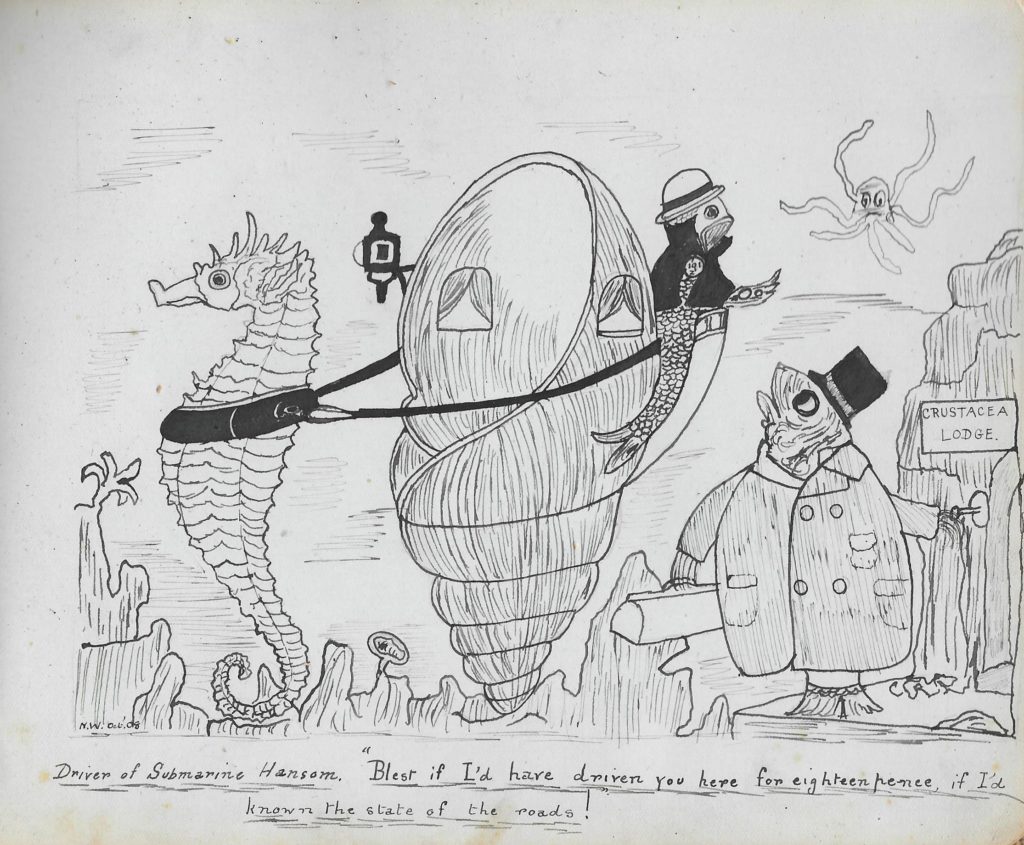

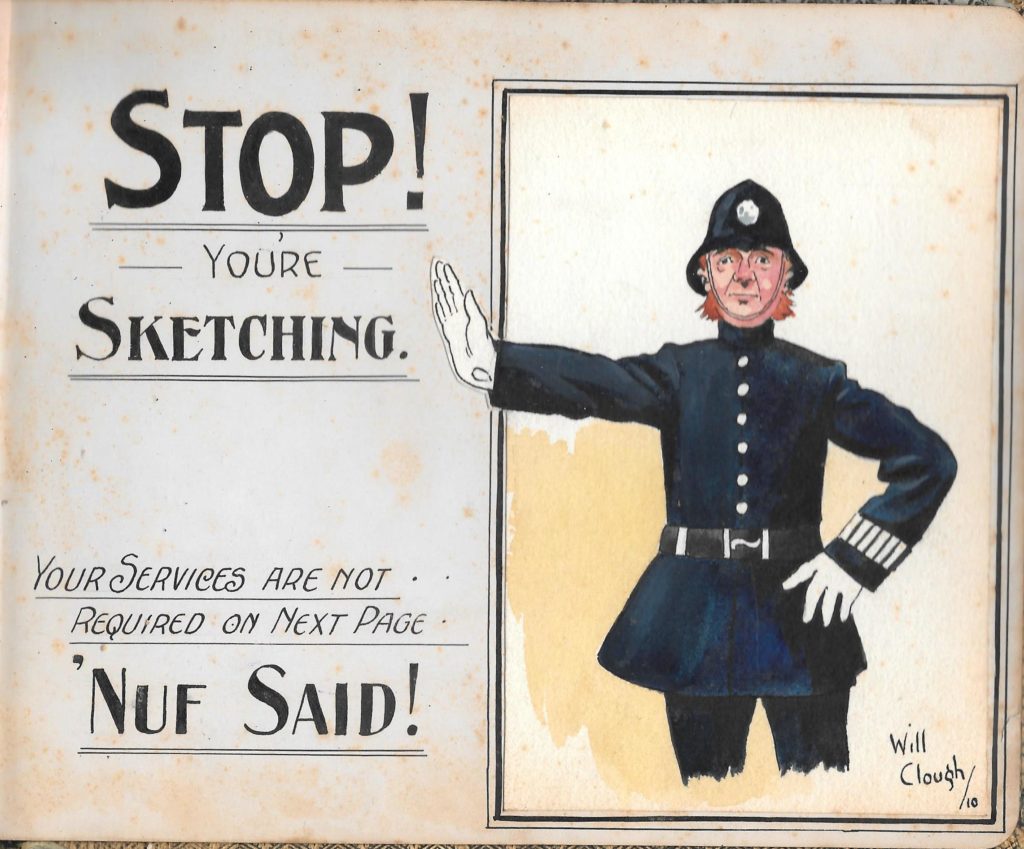

The album itself is more than a simple scrapbook; it is a vibrant social document. Its pages contain a fascinating array of artwork, verse, and witty or thoughtful inscriptions. The contributors, most of whom were young women also training at the college, demonstrate a range of artistic talent and literary flair. Some entries are playful, others deeply heartfelt, and all provide a rare and poignant glimpse into everyday life, hopes, and humour in Britain during the final years before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

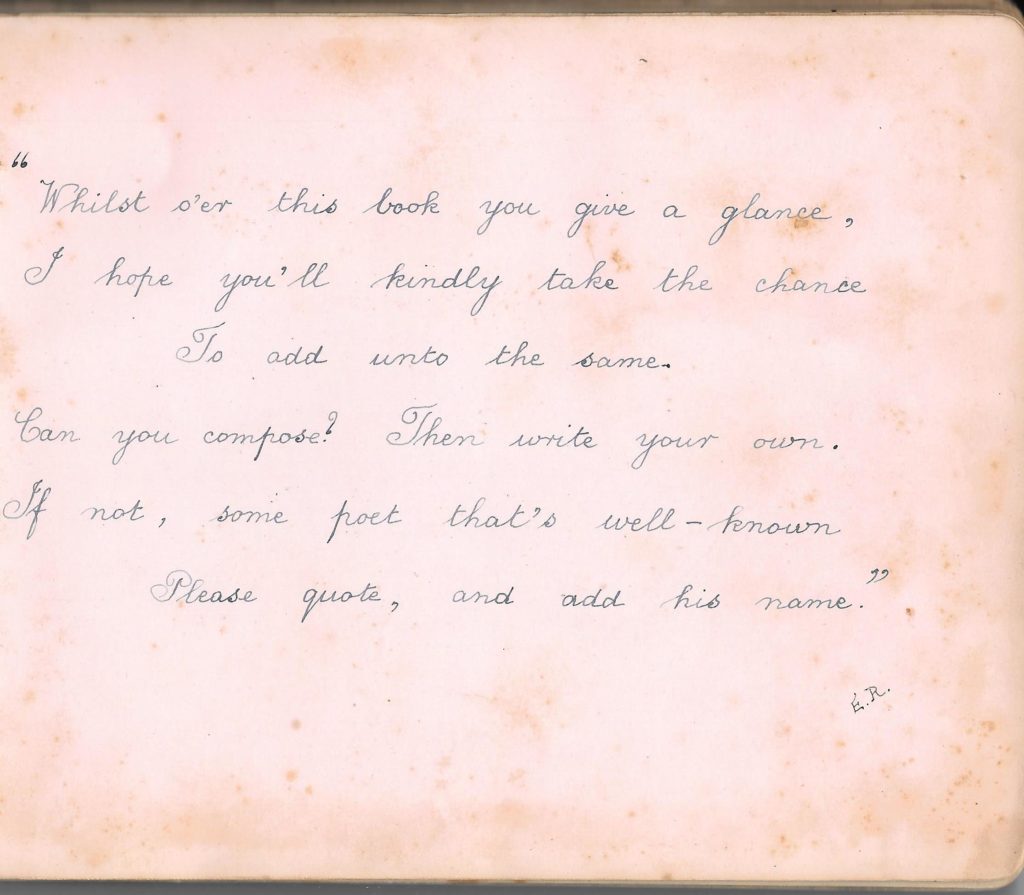

Emily set the tone for the album with a gentle, encouraging verse of her own, inscribed at the very beginning of the book:

“Whilst o’er this book you give a glance,

I hope you’ll kindly take the chance

To add unto the same.

Can you compose? Then write your own.

If not, some poet that’s well-known

Please quote, and add his name.”

— E.R.

This simple invitation reflects the Edwardian spirit of sociability, creativity, and self-expression. It also illustrates the customs of friendship and intellectual exchange among young women of the period, many of whom were among the first generations to pursue higher education and professional careers. The resulting collection offers modern readers not only a taste of individual personalities but also a unique cultural snapshot of Edwardian youth on the eve of profound social and historical change.

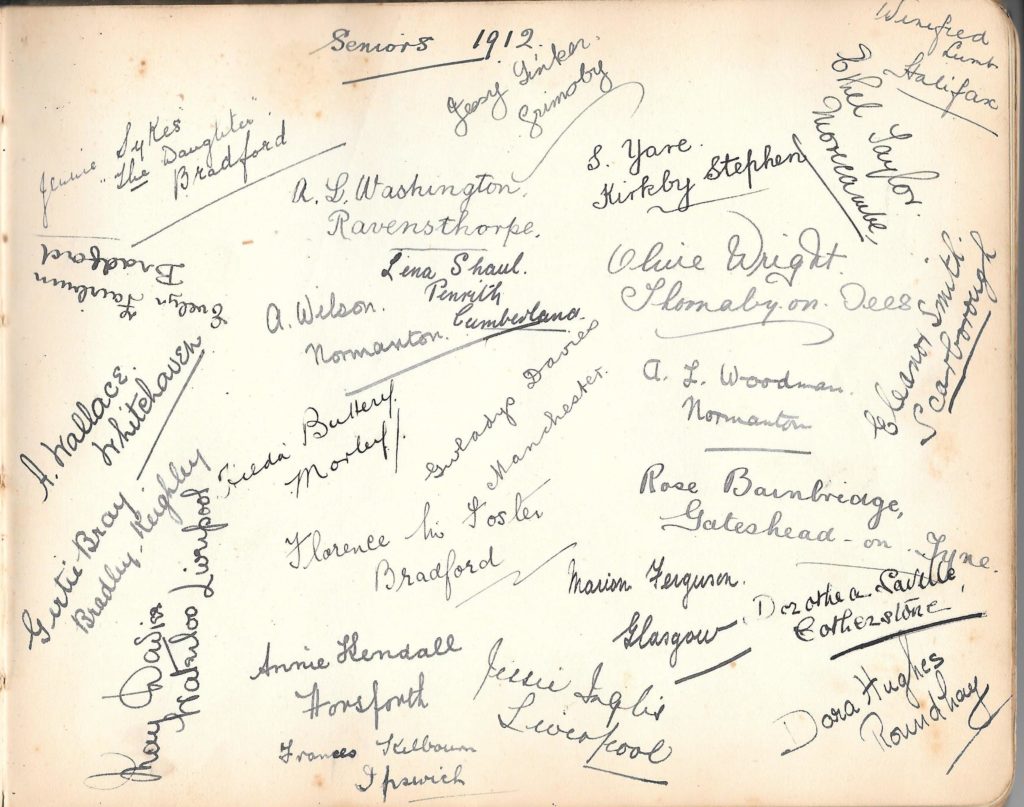

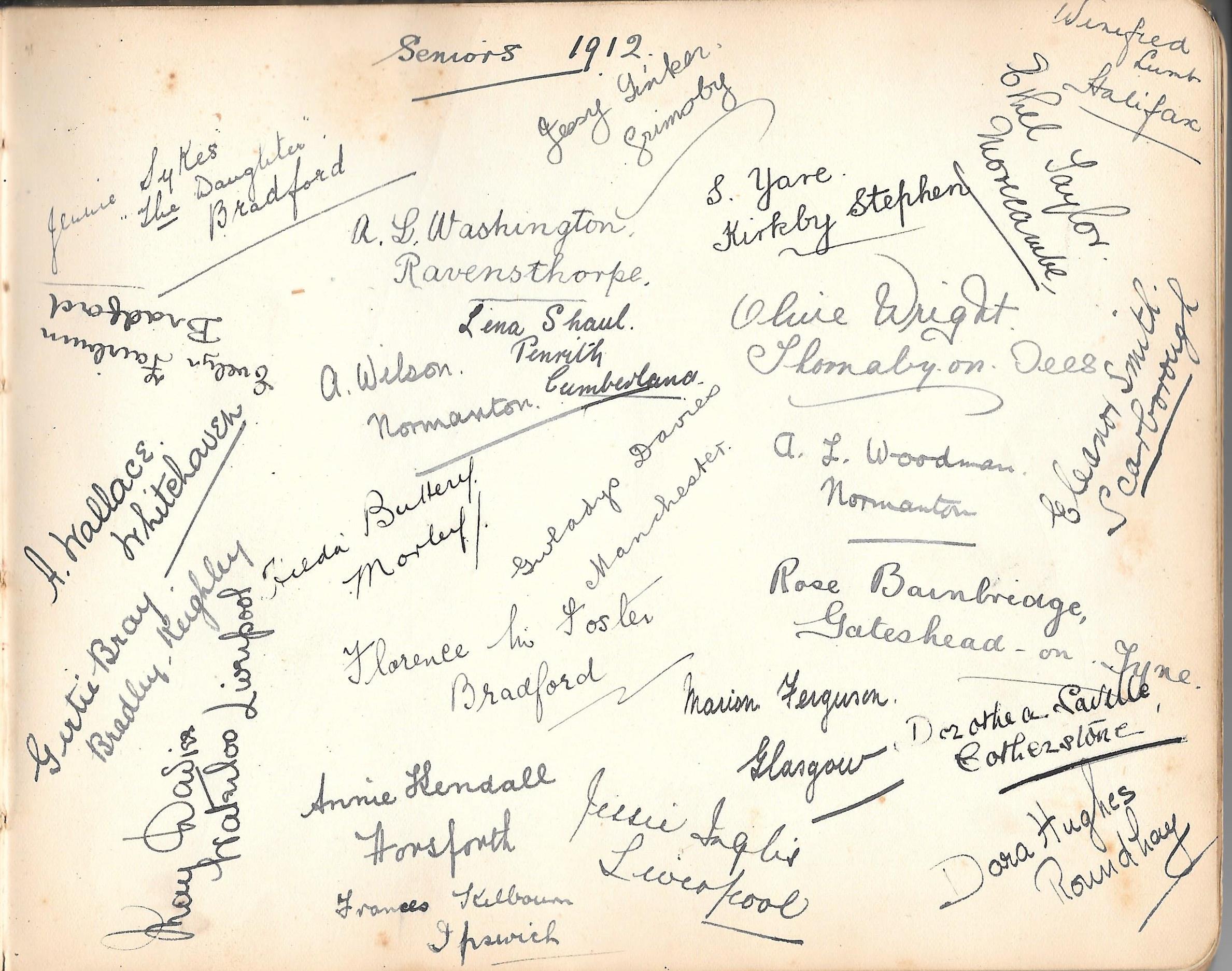

Emily’s 1912 Seniors Class: An Album of Names and Places

This page from Emily’s album, titled simply “Seniors 1912,” serves as a collective snapshot of her classmates at the end of their training. Each signature is not just a name, but a window into a life—each with its own story, accent, and hometown pride.

At the top left corner, we find Jennie Sykes, affectionately dubbed “The Daughter,” hailing from Bradford. Her distinctive title hints at a role or reputation cherished among her peers.

Centrally positioned at the top is George Sinker of Grimsby, whose name stands out among the mostly female company, suggesting the inclusive and supportive atmosphere of Emily’s training cohort.

Over to the upper right, Wansford Limb from Halifax adds his name, while directly beneath, the vertical script of Ethel Taylor of Morecambe and S. Yare from Kirkby Stephen in Westmorland appear—names that trace the class’s reach from Yorkshire to the edges of Cumbria.

On the right edge, in a slanting hand, Eleanor Smith from Scarborough claims her place, representing the North Sea coast.

At the centre right, we see Olive Wright, who gives her location as “Shomlay on Tees”—possibly a variant or mishearing of a more familiar Teeside place, now lost to time.

Just below the centre right, A. L. Woodman of Normanton and Rose Bainbridge from Gateshead-on-Tyne (Tyneside) leave their marks, while at the bottom right, Dora Hughes of Roundhay signs in a neat, flowing style.

Below the centre, Dorothea Suttle of Cotterstock and Marian Ferguson of Glasgow add their names, showing the breadth of backgrounds in the class—from Northamptonshire all the way to Scotland.

At the heart of the page, Gladys Davis of Manchester is inscribed, representing the industrial North West.

Just left of centre, Lena Shall from Penrith, Cumberland and A. Wilson of Normanton appear, while a little further down, Treda Butterly of Morley and Florence L. Foster from Bradford are present, the latter’s name appearing twice—testament to close friendships or fond memories.

On the left margin, A. Wallace of Whitelaws is inscribed vertically, alongside Gertie Bray from Bingley, Keighley, whose name traces a line from the Dales to the classroom.

In the bottom left corner, slanting upwards, Lucy Quales of Waterloo, Liverpool is found, and nearby, Annie Hendall of Horsforth and Frances Kelburn from Ipswich appear at the bottom edge, adding East Anglia to this tapestry of locations.

Jennie Inglis, representing Liverpool, signs at the bottom centre, while Marion Ferguson of Glasgow appears again, her name echoing across the page.

Finally, just above Annie Hendall, Florence L. Foster of Bradford makes her second appearance—her presence doubly noted among this vibrant network of friends and future teachers.

Each signature on this page is a fragment of a larger story: young lives from across England and Scotland, briefly united at a Leeds college in 1912, soon to be scattered again by geography, career, and—tragically—history itself. The album preserves their names and hometowns, offering a rare and personal record of Edwardian youth on the eve of a world about to change forever.

Emily Rourke’s Autograph Album: An Intimate Archive of Edwardian Life

The discovery and preservation of Emily Rourke’s autograph album, begun in Leeds in 1908, offers an extraordinary lens onto the lives, friendships, and aspirations of Edwardian youth on the threshold of modernity and, unknowingly, on the brink of a world transformed by war. More than a simple scrapbook, Emily’s album is a social artefact—a communal artwork and written record—capturing the fleeting but deeply felt bonds among a generation of teacher trainees whose lives would be shaped by the seismic changes of the twentieth century.

The Work and the Archive

Emily’s album was started on Saturday, 19th September 1908, when she was just seventeen. At the time, she was training to become a teacher at a college in Leeds, part of a close-knit cohort of mostly young women drawn from across England and Scotland. The tradition of keeping a “friendship album” or autograph book was already well established in Victorian and Edwardian society, but Emily’s version is unusually rich both in scope and content. The pages contain not only signatures, but carefully rendered sketches, poetry, witty observations, and sometimes poignant personal reflections.

This archive is doubly significant: it preserves individual voices—each one identified by name, date, and home town—but it also documents a social world. The contributors include classmates, friends, and a handful of young men (notably George Sinker of Grimsby), reflecting both the professional aspirations and the social boundaries of the era. The album’s structure and contents reveal patterns of intimacy, collegiality, and creativity. The “Seniors 1912” page, for example, functions almost as a roll call or commemorative register for Emily’s final year at college, with signatures clustering from as far afield as Glasgow, Ipswich, and the industrial cities of the north.

Edwardian Life and the World of Women’s Education

The album is situated firmly in the Edwardian era (1901–1914), a time often mythologised for its social elegance and optimism but marked, in reality, by profound currents of change. For young women like Emily, the pursuit of professional training was itself relatively new. The expansion of teacher training colleges in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain enabled increasing numbers of women to seek both education and careers outside the home. This was a generation for whom the “New Woman” was a living ideal, not just a magazine trope.

Life at college, as glimpsed through the album, was communal, supportive, and intellectually stimulating, but also laced with the anxieties of coming adulthood. Many of the album’s contributors are quick to share a joke, a scrap of verse, or a meaningful sketch—tiny testaments to both their individuality and their shared experience. There is a strong sense of optimism and solidarity, as well as the quiet pride of young people making their way in a rapidly changing society.

Yet, this was still a world constrained by class and gender expectations. The act of signing an album and noting one’s home town was, in a sense, an act of self-definition and declaration: a reminder of where each student came from, and perhaps where they hoped to return or what they aspired to become. The page is populated by a remarkable geographical diversity—Bradford, Scarborough, Kirkby Stephen, Glasgow, Liverpool, and more—signifying the national reach of women’s education in the period, as well as the strong regional identities of Edwardian Britain.

What We Know About Emily Rourke

Although details about Emily Rourke’s later life remain relatively scarce, we can reconstruct aspects of her biography from surviving records. The 1911 census records Emily, then in her early twenties, as a student teacher residing in Leeds, along with several of her friends and fellow trainees whose names also appear in the album. This snapshot situates Emily at the heart of the educational reforms and ambitions of the period.

Emily’s choice to start the album—and her poetic opening invitation—reveals a young woman of creativity, sociability, and considerable emotional intelligence. She asks her friends to “add unto the same,” encouraging original composition but accepting the quoting of “some poet that’s well-known.” The tone is democratic and inclusive, reflecting the educational ethos of the time. The album is thus a collaborative creation, shaped by Emily but enriched by the voices and talents of dozens of peers.

It is not yet known where Emily’s later career and life led her—whether she remained in teaching, started a family, or faced the profound disruptions of the First World War. The album itself, however, survives as a testament to her role as a social catalyst and record-keeper. Each signature and drawing speaks not only of personal connection, but also of Emily’s gift for creating community.

The Value of the Archive

For historians and family researchers, Emily Rourke’s autograph album is a rare prize. It provides first-hand evidence of the networks, friendships, and aspirations of Edwardian women and men on the cusp of professional life. The names and places documented within can be traced through public records, allowing for genealogical connections and social histories to be reconstructed. The artistic and literary contributions offer a unique window onto the imaginative lives of young people whose voices were often omitted from official archives.

Above all, the album reminds us of the power of ordinary lives and ordinary artefacts. Through Emily’s eyes—and the hands of her friends—we glimpse a lost world: one of hope, humour, and human connection, rendered all the more poignant by our knowledge of what the next decade would bring.

Conclusion

Emily Rourke’s autograph album is more than an object of nostalgia; it is a living document of Edwardian society at a moment of transition. It speaks to the emergence of new roles for women, the spread of education, and the enduring bonds of friendship and place. Its preservation as an archive is a gift to the present—a reminder of the worlds that once were, and the people, like Emily, who shaped them with grace, humour, and the courage to sign their names.