About the John Marlow Family Letters Archive

John Marlow was born on 26 April 1937 in Leicester to Martin Edward Marlow (1905–1975) and Andrey Minnie Hylda Marlow, née Simpson (1905–1989). He grew up alongside his younger brother, Christopher (1943–1989), also born in Leicester. John’s life came to a close in Sheffield, Yorkshire, on 26 July 2003, aged 66.

The John Marlow family letters archive is a unique collection documenting two generations of the Marlow and Banks families of Leicester, Clay Cross, and Chesterfield.

During his youth, John experienced two significant hospital stays at Leicester Royal Infirmary, in 1954 and again in 1957. These periods, while challenging, became formative as John exchanged letters with numerous friends he made during his time in hospital—friendships that continued long after his discharge. The collection now includes a number of these letters, sent to both his family home in Leicester and directly to his hospital ward, reflecting a network of friends and relatives who cared deeply for him.

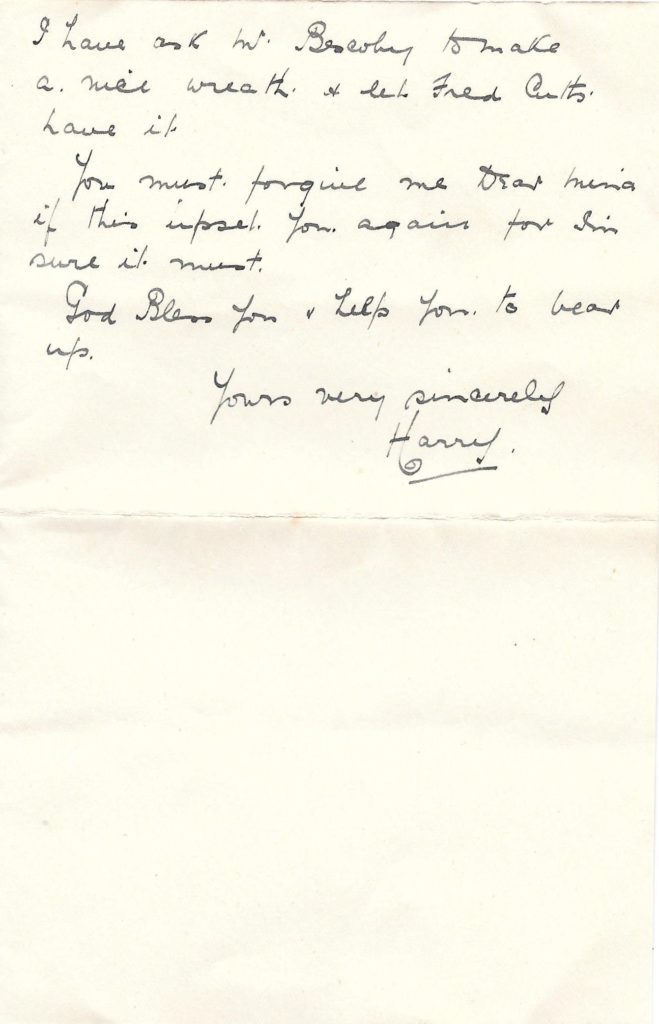

Reaching back to the previous generation, the John Marlow family letters archive also contains correspondence addressed to Mina (Wilhelmina) Banks of Market Street, Clay Cross (1898–1964), who appears to be a relative of John Marlow. Many of these letters relate to Edward Lewis Towndrow (b. 1894, Chesterfield), a young man with whom Mina shared a close, affectionate bond until his untimely death on 21 February 1927. Among these is a poignant letter Edward wrote to Mina from Torquay in August 1926, less than a year before his death. Afterward, Mina commissioned a memorial stone for Edward and received letters of condolence from friends and family, now preserved in the archive.

This interesting collection of personal letters, documenting the emotional connections and histories of the Marlow and Banks families, was acquired on 11 November 2019.

Explanation & Meaning

-

Genealogical Significance:

The document provides a concise family tree and places individuals within their social and geographical context (Leicester, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Sheffield). -

Personal and Social History:

The letters offer a window into postwar British society, hospital life, and the enduring value of correspondence for maintaining friendships and family ties, especially during times of illness and loss. -

Emotional Value:

Both John’s and Mina’s stories highlight the role of letters in expressing and sustaining relationships—whether between young friends recovering in hospital, or a woman mourning the loss of a loved one. -

Archival and Research Importance:

Acquiring such a collection provides historians, genealogists, or the family itself with an authentic, unfiltered record of real lives, affections, and bereavements across two generations. -

Legacy:

By preserving these letters, the family’s experiences—especially those of friendship, illness, love, and loss—are documented for future reflection or research, turning private correspondence into a public or historical resource.

In summary:

The John Marlow family letters archive is a treasure trove of personal history, documenting the everyday realities, trials, and affections of two linked families from the early 20th century through to the postwar years. It offers insight into the social customs of friendship and mourning, as well as the evolving nature of family connections across generations.

John Marlow (1937-2003) page two here

The Transcriptions

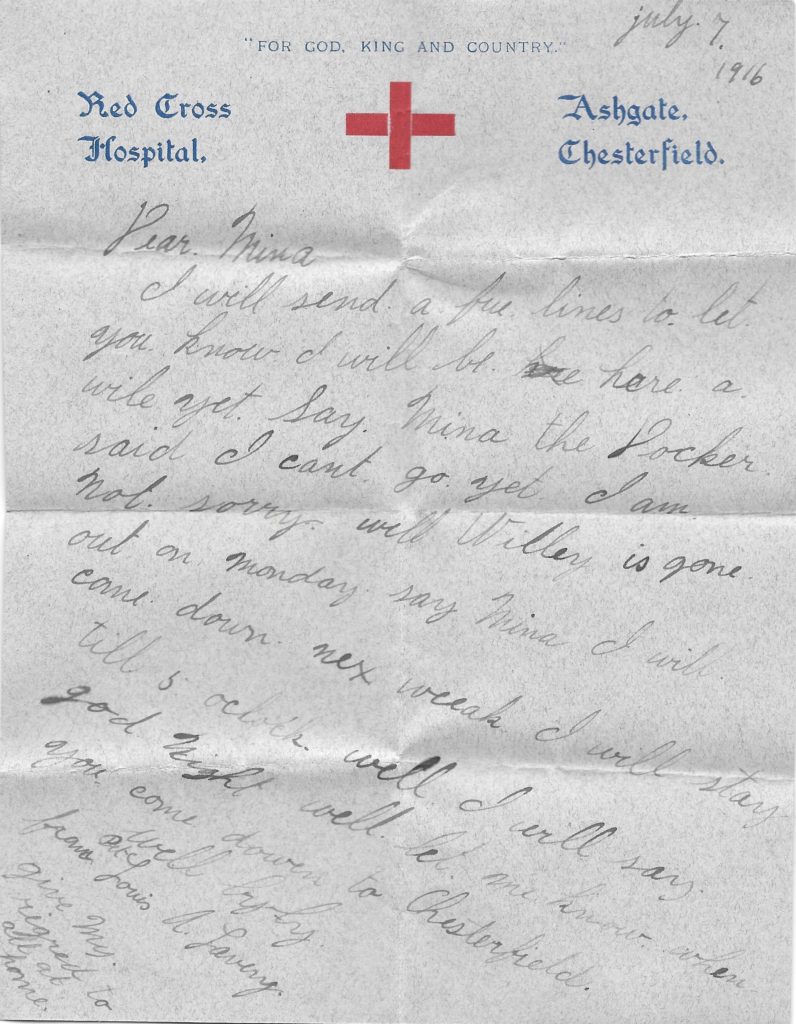

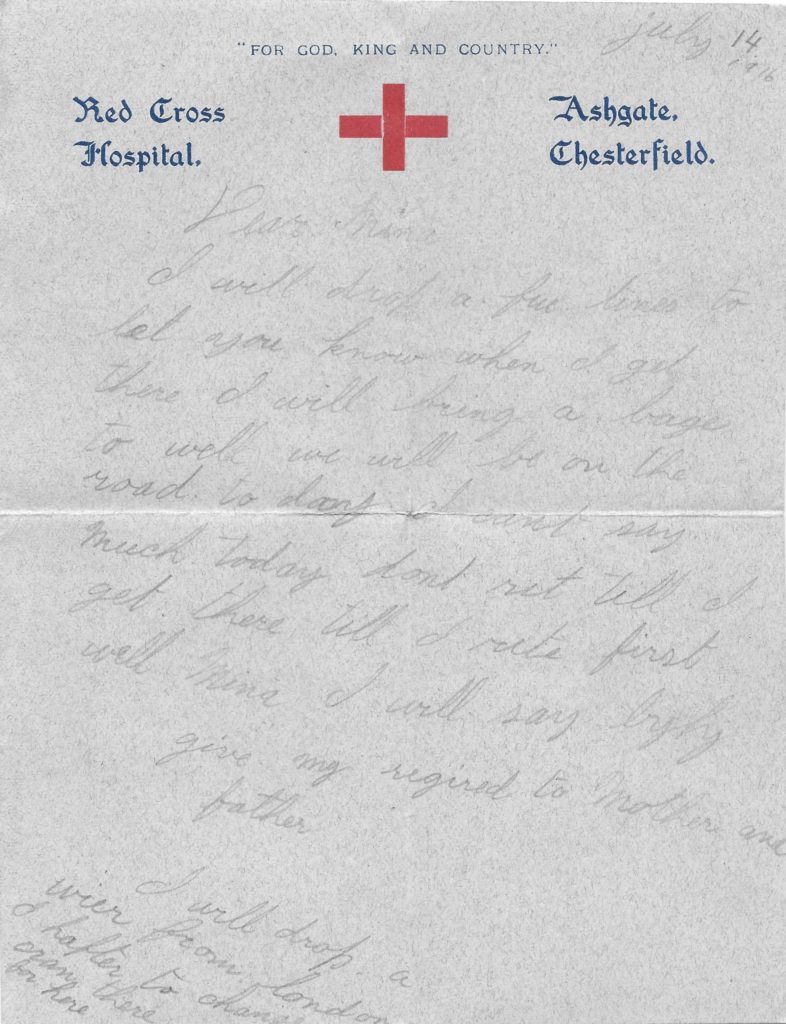

While the primary focus of this collection is the correspondence and personal papers of John Marlow (born 1937), it also includes several earlier items—most notably a letter dated 1916 from the Red Cross Hospital, Ashgate, Chesterfield. The presence of this First World War-era letter, despite predating John’s birth by more than two decades, is a testament to the family’s practice of preserving important documents and correspondence across generations. Such archival mingling is not uncommon; families often retain letters of sentimental, commemorative, or genealogical value, passing them down alongside more recent materials. The inclusion of this 1916 letter enriches the historical context of the Marlow family archive, offering a tangible link to earlier events and relationships that helped shape the family’s story throughout the 20th century:

Red Cross Hospital,

Ashgate, Chesterfield.

“For God, King and Country.”

July 7, 1916

Dear Mina,

I will send a few lines to let you know I will be here a while yet. Say, Mina, the doctor said I can’t go yet. I am not sorry. Well, Willer is gone out on Monday. Say, Mina, I will come down next week. I will till 5 o’clock. I will stay. God wish. Well, I will say good-bye, well let me know when you come down to Chesterfield.

From Louis H. Towndrow

Give my respects to all at home.

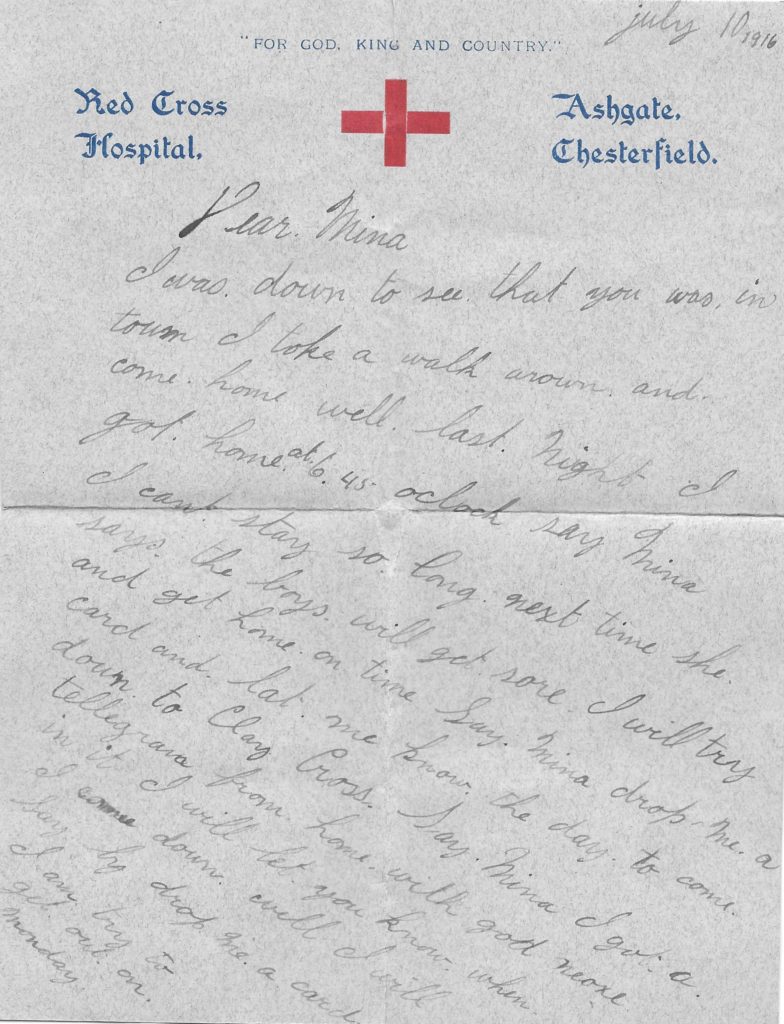

Red Cross Hospital,

Ashgate, Chesterfield.

“For God, King and Country.”

July 10, 1916

Dear Mina

I was down to see that you was in town I toke a walk around and come home well. last. night I got home at 6.45 oclock. say Mina I cant stay so long next time she says the boys will get sore and get home on time. Say Mina I will try and call and let me know the day to come down to Clay Cross. Say Mina drop me a telegram from home will be good I will come down. well let me know I wish I am by dad could I with I am trying to get any on Monday.

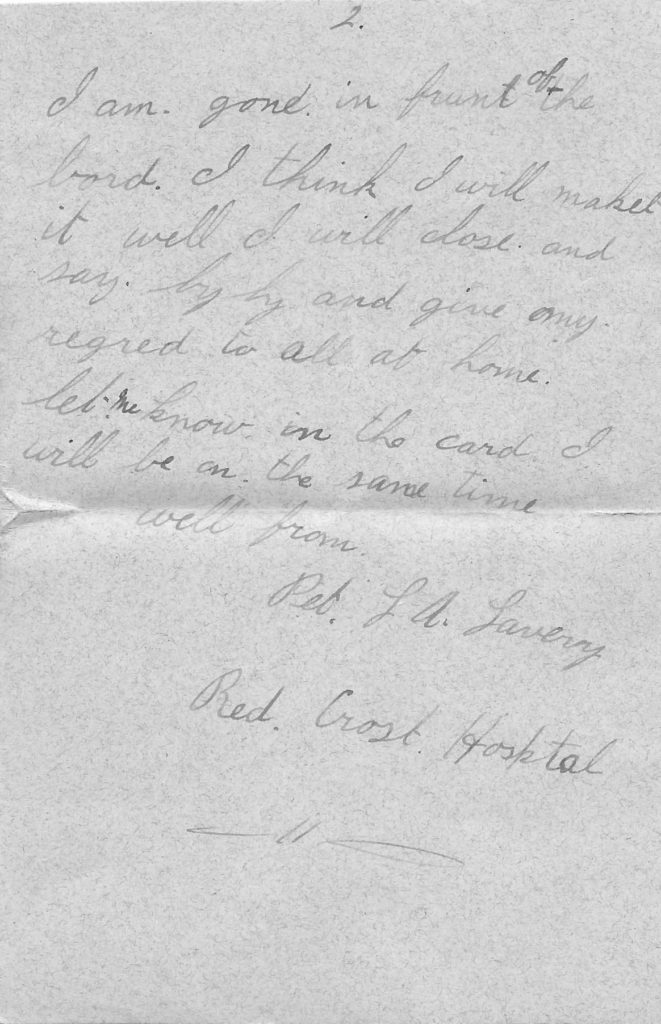

I am gone in fount of the lord. I think I will make it well it will close. and say by by and give my regred to all at home.

let me know in the card I will be on the same time

well from

Pte. L. H. Towndrow

Red. Crosst. Hostal

Red Cross Hospital,

Ashgate, Chesterfield.

“For God, King and Country.”

July 14, 1916

Dear Mina

I will drop a few lines to let you know when I get there I will bring a horse to well we will be on the road so long I cant say much today bad not till I get there till I rite first well Mina I will say by by give my regard to mother and father.

I will drop a river from London I rather to change my army here to London.

Red Cross Hospital,

Ashgate, Chesterfield.

“For God, King and Country.”

July 14 / 16

Dear Mina

I will drop a few lines to let you know when I get there I will bring a horse to well we will be on the road so long I cant say much today bad not till I get there till I rite first well Mina I will say by by give my regard to mother and father.

I will drop a river from London I rather to change my army here to London.

Notes:

-

The phrase “I will drop a river from London” appears to be a miswriting—likely “I will drop a [line/letter] from London.”

-

The word “bad” may be a miswriting or misspelling of “but” (“much today but not till I get there…”).

-

The handwriting is very faint, but all visible words are included here.

Explanation: Why Is a 1916 Letter in a 1930s-Born Boy’s Collection?

-

Family Preservation of Correspondence

-

Letters, especially from periods like the First World War, were often treasured and kept by families. They could be passed down from parents, aunts, uncles, or grandparents, especially if the writer or recipient was a close relative.

-

The 1930s-born boy (likely John Marlow, from your previous message) may have inherited or been given these letters by older family members, particularly if he was interested in family history or was seen as the “keeper” of family records.

-

-

Archival “Mingling”

-

When family papers are boxed together over generations, it’s very common to find earlier correspondence among much later items. This happens as collections are moved, merged, or reorganized with each new generation.

-

-

Commemorative or Emotional Significance

-

The 1916 letter could have special meaning (perhaps the author was a relative lost in the war, or a beloved uncle, or simply part of a family story), which led to its preservation alongside more recent letters.

-

-

Indirect Relationship

-

Even if the boy in the 1930s wasn’t directly connected, he could have acquired the letter as part of a broader family archive (including documents belonging to great-aunts, uncles, cousins, etc.).

-

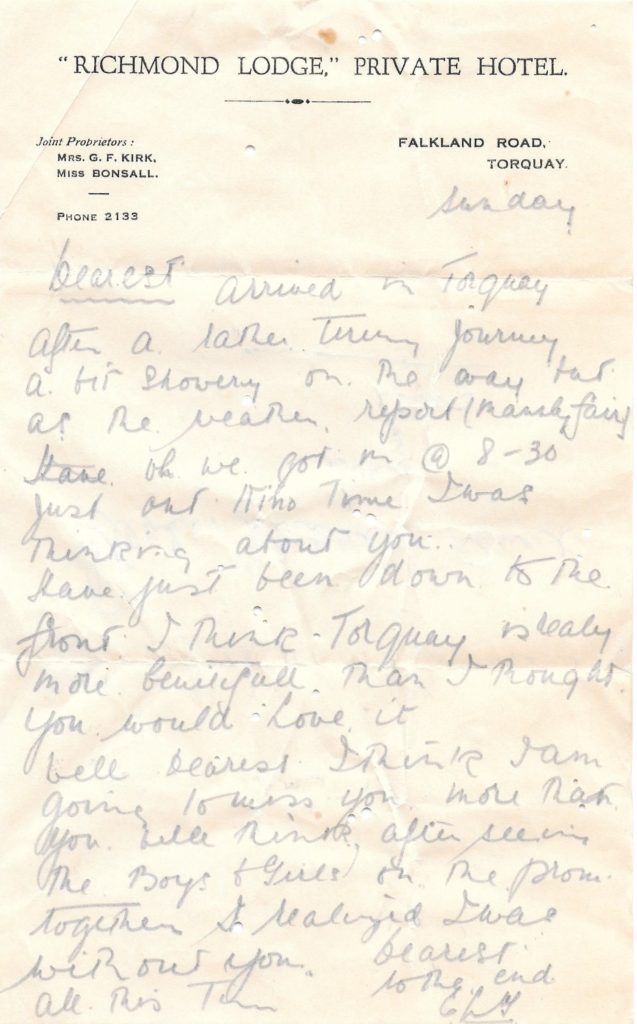

Letter from Ed to Mina, Richmond Lodge, Torquay – 15 August 1926

This affectionate letter was written by Edward Lewis Towndrow to Mina Banks while staying at Richmond Lodge, Torquay. Ed describes his journey, impressions of Torquay’s beauty, and the deep sense of longing he feels for Mina, particularly when observing couples strolling along the promenade. The letter captures both the tenderness and loneliness of separation during a 1920s English seaside holiday:

“RICHMOND LODGE,” PRIVATE HOTEL.

FALKLAND ROAD, TORQUAY.

Joint Proprietors:

MRS. G. F. KIRK,

MISS BONSALL.

Phone 2133

Sunday

Dearest

Arrived in Torquay after a later, tiresome journey. A bit showery on the way, but as re weather, report (Manch fairy) same. Oh we got in @ 8-30 just out Nino time. I was thinking about you…

Have just been down to the front. I think Torquay is really more beautiful than I thought. You would love it.

Well dearest, I think I am going to miss you more than you will think, after seeing the boys & girls on the prom together I realized I was without you.

All for this time

Dearest

Long end

Ed.

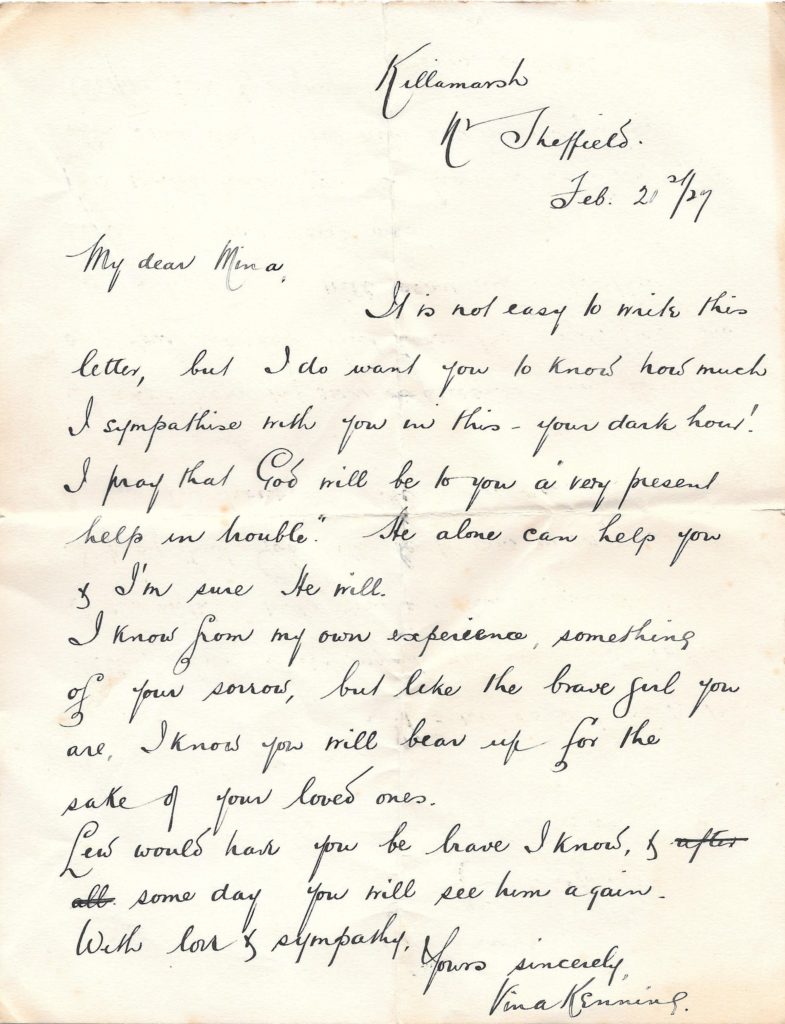

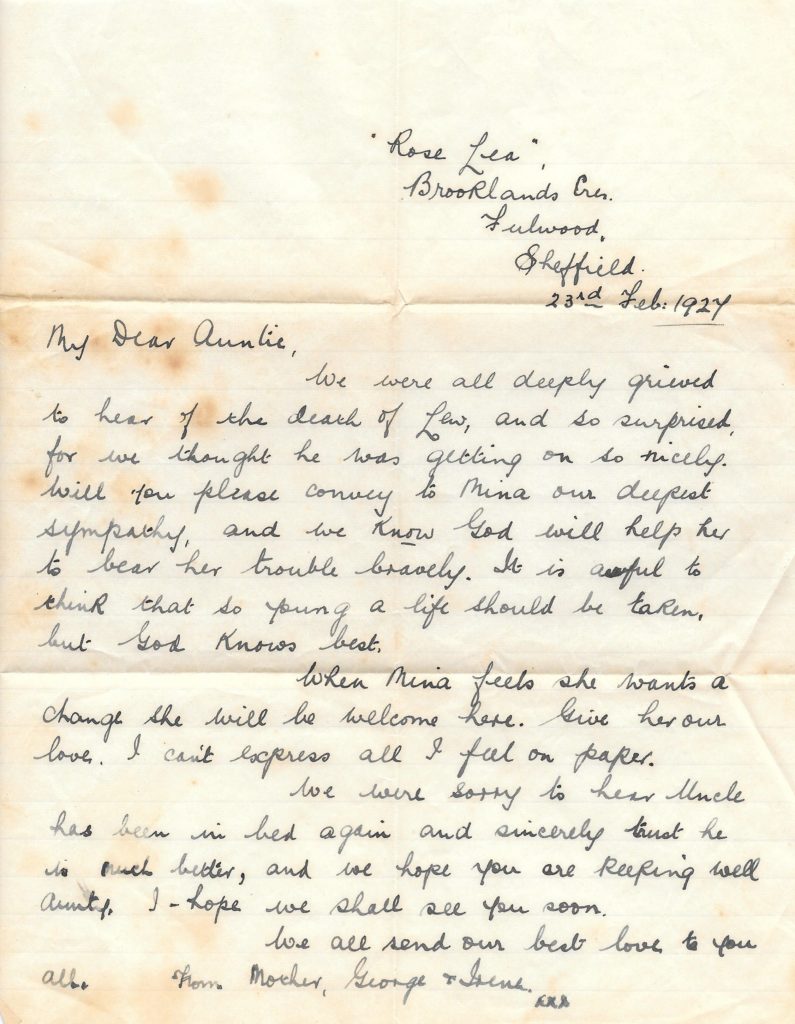

Letter of Condolence to Mina Banks, 21 February 1927

In this heartfelt letter, Vina Henning of Killamarsh, near Sheffield, writes to Mina Banks to express deep sympathy following the death of Edward (“Lew”) Towndrow. Vina offers words of comfort rooted in faith and personal experience, encouraging Mina to remain brave and hopeful for a future reunion. The letter reflects the era’s customs of mourning, emotional support, and the enduring strength of friendship and community.

Transcription

Killamarsh

Nr Sheffield

Feb. 21st / 27

My dear Mina,

It is not easy to write this letter, but I do want you to know how much I sympathise with you in this – your dark hour!

I pray that God will be to you “a very present help in trouble.” He alone can help you & I’m sure He will.

I know from my own experience, something of your sorrow, but like the brave girl you are, I know you will bear up for the sake of your loved ones.

Lew would have you be brave I know, & after all, some day you will see him again.

With love & sympathy,

Yours sincerely,

Vina Henning.

Explanation

This is a condolence letter sent to Mina on 21 February 1927, shortly after the death of Edward (“Lew”). The writer, Vina Henning of Killamarsh near Sheffield, expresses heartfelt sympathy and offers comfort through faith, quoting scripture (“a very present help in trouble”). Vina acknowledges the difficulty of Mina’s sorrow but encourages her to be brave for the sake of her family, assuring her that Edward would want her to have courage. She closes with a note of hope, suggesting that Mina and Lew will one day be reunited.

This letter is a touching example of postwar condolence, blending personal empathy, religious reassurance, and a call for emotional resilience. It reflects the customs of the time and the supportive bonds within the community.

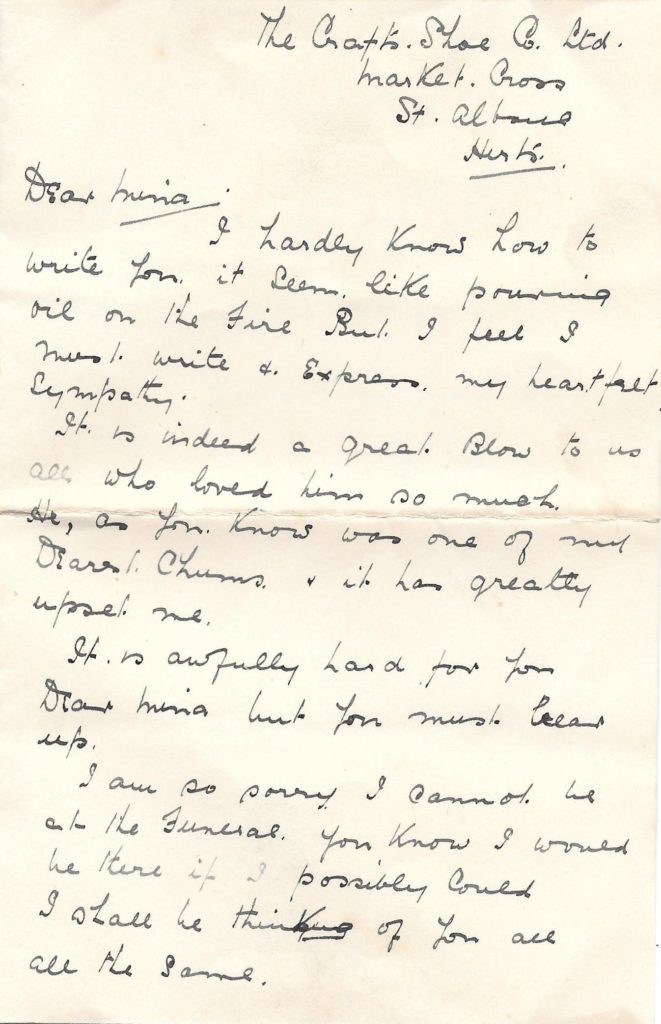

Condolence Letter from Harry to Mina Banks, St. Albans, 22 February 1927

The Crafts. Shoe Co. Ltd.

Market Cross

St. Albans

Herts.

Dear Mina,

I hardly know how to write for it seems like pouring oil on the fire. But I feel I must write & express my heartfelt sympathy.

It is indeed a great blow to us all who loved him so much. He, as you know, was one of my dearest chums & it has greatly upset me.

It is awfully hard for you dear Mina but you must bear up.

I am so sorry I cannot be at the funeral. You know I would be there if I possibly could. I shall be thinking of you all the same.

I have ask Mr. Beesley to make a nice wreath & let Fred Ants have it.

You must forgive me dear Mina if this upsets you again for I’m sure it must.

God Bless you & help you to bear up.

Yours very sincerely

Harry.

Explanation

This is a heartfelt condolence letter written to Mina Banks by her friend Harry, on company stationery from The Crafts Shoe Co. Ltd. in St. Albans, Hertfordshire, dated 22 February 1927. Harry expresses deep sorrow at the death of a mutual friend—presumably Edward (“Lew”) Towndrow—whom he describes as one of his “dearest chums.” The writer admits difficulty in finding the right words, fearing that any letter might only deepen Mina’s pain, but feels compelled to share his sympathy.

Harry acknowledges his own grief and recognizes that Mina’s loss is even harder to bear, urging her gently to “bear up” in the face of tragedy. He apologizes for being unable to attend the funeral but reassures Mina of his thoughts and support. To show his respect, Harry has arranged for a wreath to be made by Mr. Beesley and delivered by Fred Ants.

The letter closes with an apology in case his words cause Mina more pain, and a benediction—“God Bless you & help you to bear up”—reflecting the care and supportive bonds of the time.

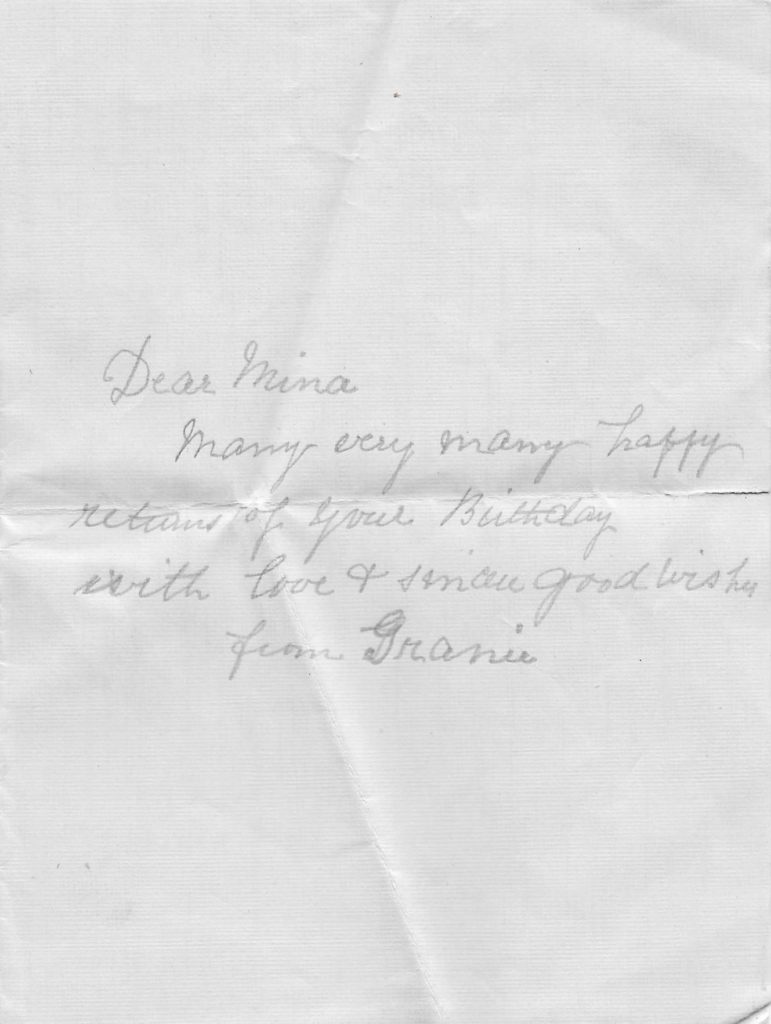

Family Condolence Letter to Auntie (re: Lew), Sheffield, 23 February 1927

Full Transcription

“Rose Lea”

Brooklands Cres.

Fulwood.

Sheffield.

23rd Feb. 1927

My Dear Auntie,

We were all deeply grieved to hear of the death of Lew, and so surprised, for we thought he was getting on so nicely. Will you please convey to Mina our deepest sympathy, and we know God will help her to bear her trouble bravely. It is awful to think that so young a life should be taken, but God knows best.

When Mina feels she wants a change she will be welcome here. Give her our love. I can’t express all I feel on paper.

We were sorry to hear Uncle has been in bed again and sincerely trust he is much better, and we hope you are keeping well Auntie. I hope we shall see you soon.

We all send our best love to you all.

From Mother, George & Irene.

Explanation

This letter, sent from “Rose Lea” in Sheffield on 23 February 1927, is addressed to “Auntie” from three family members: Mother, George, and Irene. The letter conveys the family’s deep sorrow and shock at the death of Lew (Edward Lewis Towndrow), mentioning they had hoped he was recovering. The writers ask Auntie to pass along their heartfelt sympathy to Mina (Lew’s partner or close relative), expressing hope that God will help her endure this loss with bravery. They also offer Mina a place to stay for a change of scene whenever she feels ready, sending love and support.

The letter goes on to express concern for Uncle, who has been unwell, and sends best wishes for his recovery, as well as warm regards to Auntie. The letter is sincere and intimate, typical of close-knit families supporting each other during times of bereavement, and highlights the importance of extended family bonds in the face of sudden loss.

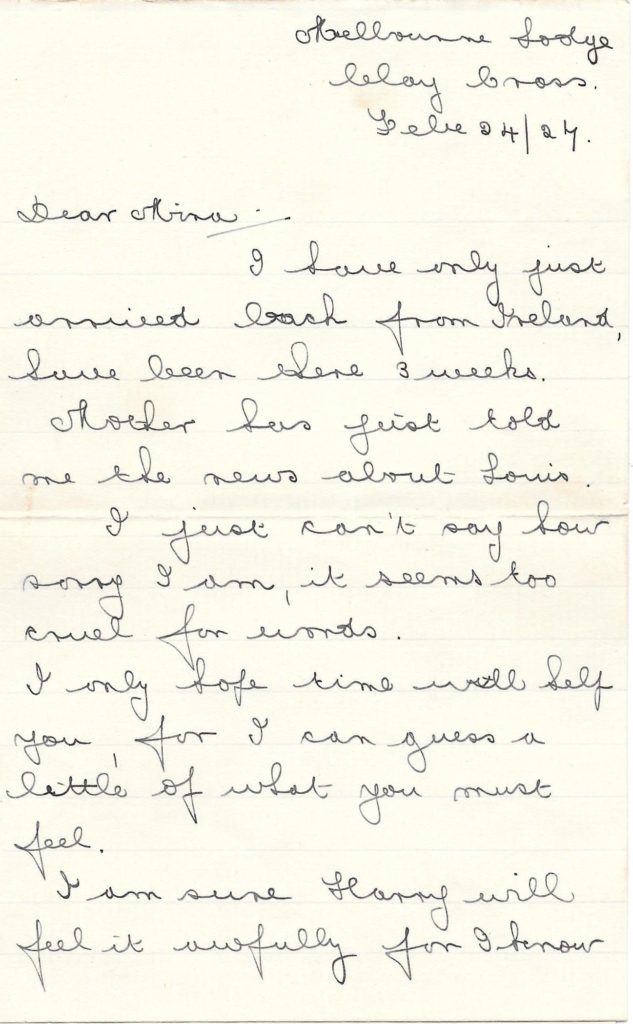

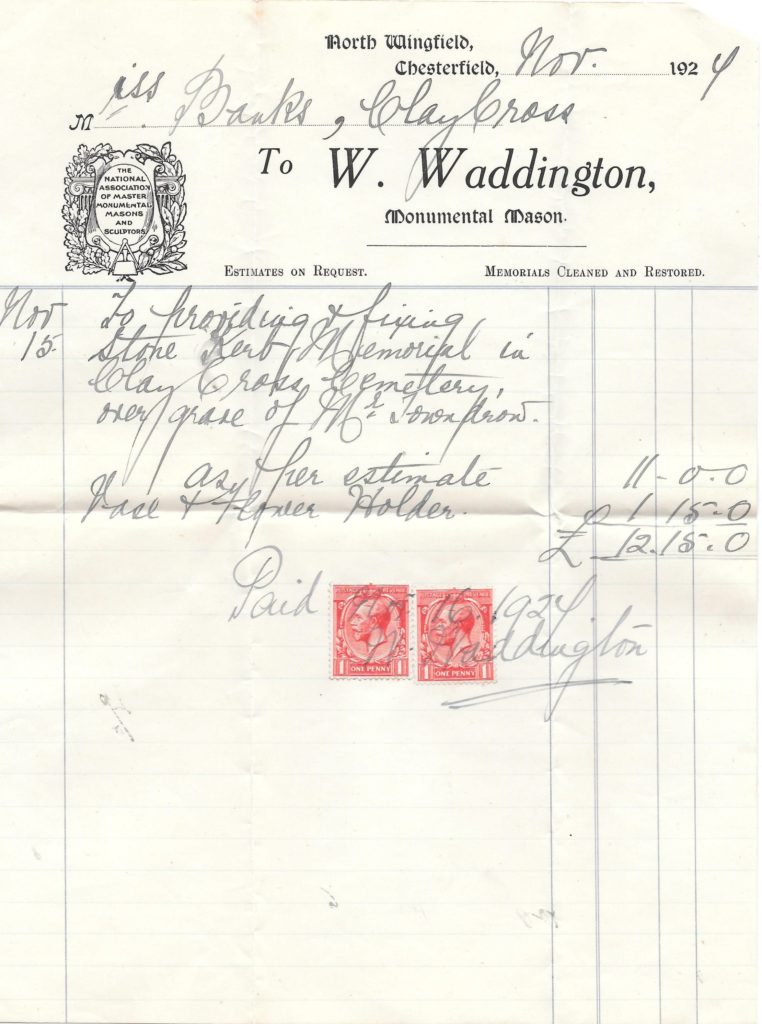

Condolence Letter to Mina from Ivy, Mellbourne Lodge, Clay Cross, 24 February 1927

Full Transcription

Mellbourne Lodge

Clay Cross

Feb 24/27.

Dear Mina,

I have only just arrived back from Ireland, have been there 3 weeks. Mother has just told me the news about Louis. I just can’t say how sorry I am, it seems too cruel for words. I only hope time will help you for I can guess a little of what you must feel.

I am sure Harry will feel it awfully for I know he thought a lot about Louis.

I shall understand quite Mina if you don’t answer this so please don’t worry.

Yours sincerely

Ivy

Explanation

This letter was written by Ivy from Mellbourne Lodge, Clay Cross, to Mina on 24 February 1927, shortly after Ivy’s return from a three-week trip to Ireland. Ivy has just learned from her mother of the death of Louis (presumably Edward Lewis Towndrow) and expresses her deep sorrow, stating the loss is “too cruel for words.” She offers the hope that time may bring some healing and acknowledges she can only imagine a fraction of Mina’s grief.

Ivy also notes that Harry (likely a mutual friend or relative) will feel the loss acutely, as he was very fond of Louis. Ivy closes with understanding, assuring Mina there is no need to reply if she is unable to, thus emphasizing empathy and the absence of any pressure during a difficult time.

This letter exemplifies the sincere, gentle condolence messages exchanged among friends and family in the aftermath of bereavement, offering emotional support and solidarity in a time of mourning.

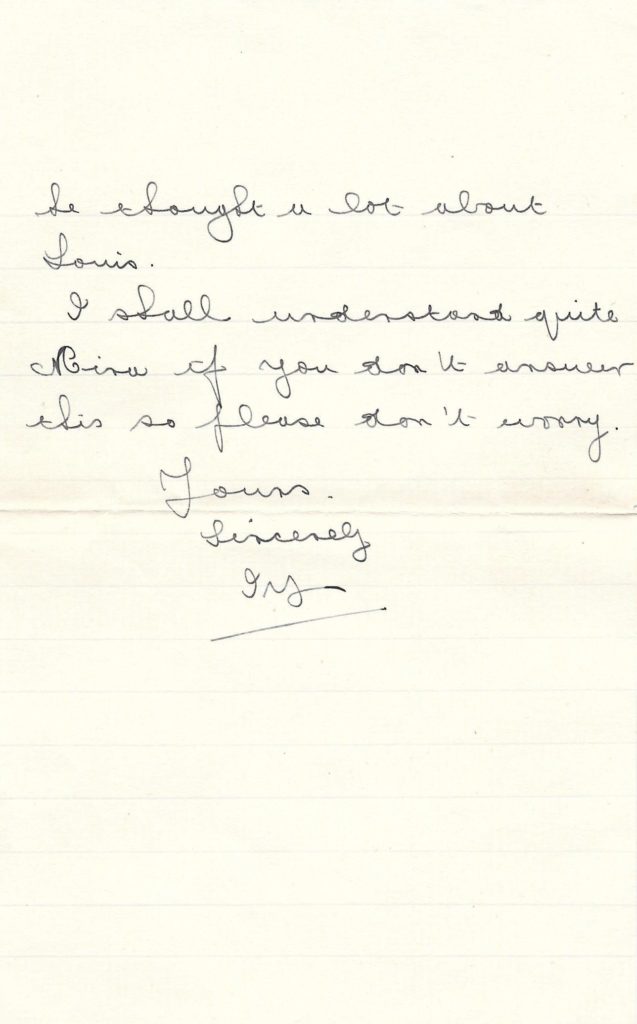

Receipt for Memorial Stone – Miss Banks, Clay Cross, 15 November 1927

Full Transcription

North Wingfield,

Chesterfield, Nov 15 1927

Miss Banks, Clay Cross

To W. Waddington,

Monumental Mason.

The National Association of Master Monumental Masons and Sculptors

Estimates on Request. Memorials Cleaned and Restored.

To providing & fixing

Stone Kerb & Memorial in

Clay Cross Cemetery,

over grave of E. L. Towndrow.

as per estimate

Face & Refiner Holder.

£11 – 0 – 0

£1 – 18 – 0

£12 – 18 – 0

Paid

[Two red “One Penny” postage stamps, cancelled]

1927

Waddington

Explanation

This document is a formal receipt and invoice from W. Waddington, Monumental Mason of North Wingfield, Chesterfield, addressed to Miss Banks of Clay Cross. It details the provision and installation of a stone kerb and memorial in Clay Cross Cemetery for the grave of E. L. Towndrow, who had died earlier that year. The total cost, as estimated and itemized, was £12 18s 0d (twelve pounds, eighteen shillings). Payment is acknowledged by the handwritten “Paid” and the signature “Waddington,” along with two cancelled penny postage stamps, a customary way to denote official payment at the time.

This receipt confirms Mina Banks’ commissioning of a permanent memorial for Edward Lewis Towndrow, and marks the final, practical stage in commemorating his life after the outpouring of condolence from friends and family. It serves as both an archival record and a poignant symbol of mourning and remembrance in the late 1920s.

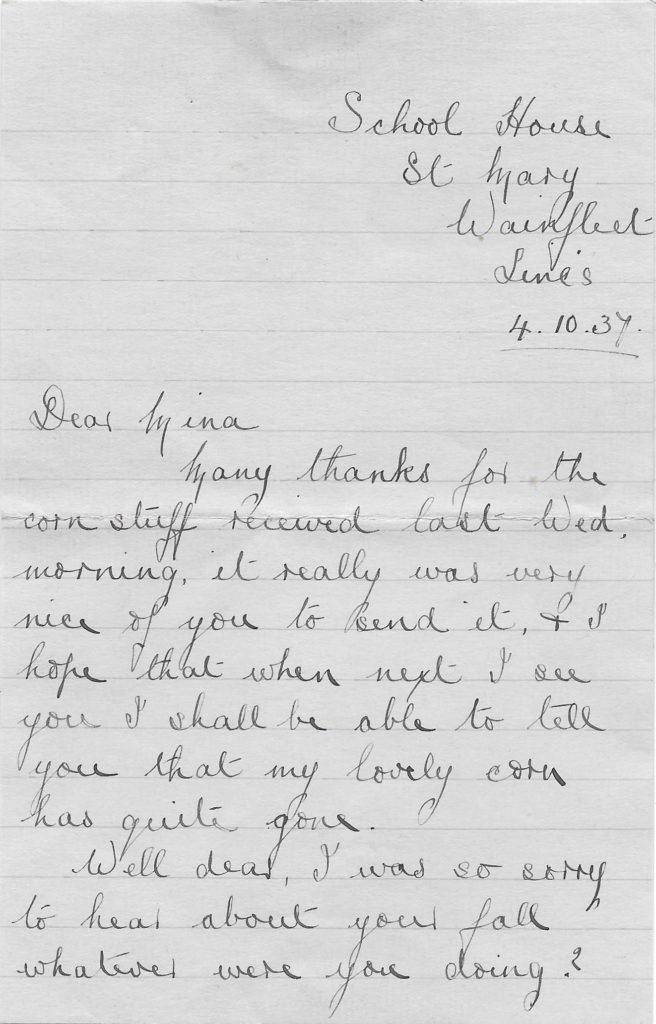

Letter from Gladys to Mina, School House, St Mary, Wainfleet, Lincs – 4 October 1937

Transcription

Page 1

School House

St Mary

Wainfleet

Lincs

4.10.37

Dear Mina

Many thanks for the corn stuff received last Wed. morning, it really was very nice of you to send it, & I hope that when next I see you I shall be able to tell you that my lovely corn has quite gone.

Well dear, I was so sorry to hear about your fall, whatever were you doing?

Page 2

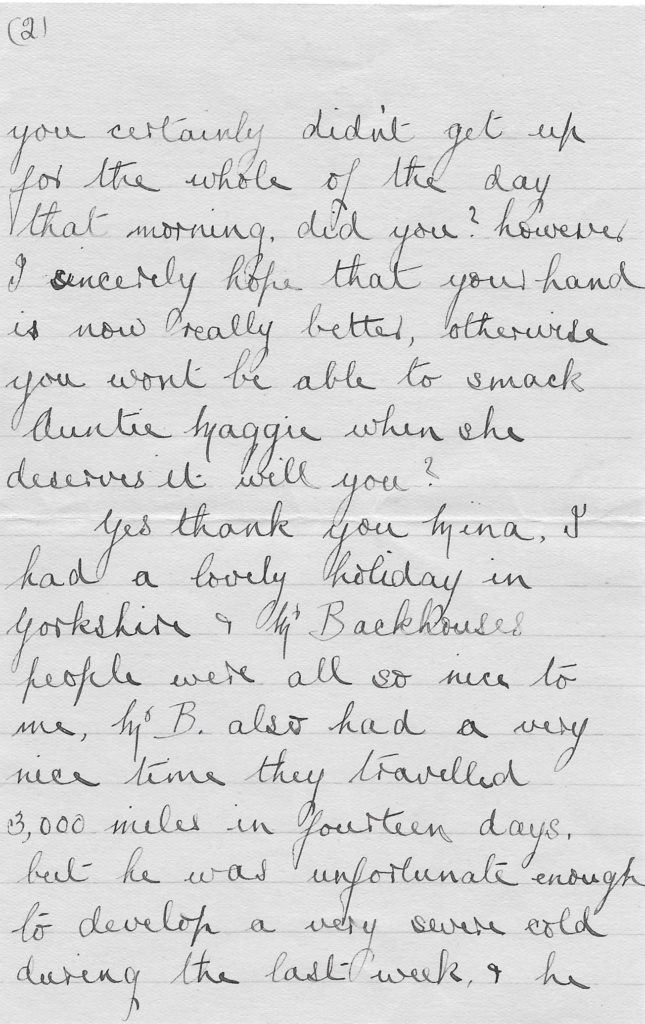

(2)

you certainly didn’t get up for the whole of the day that morning, did you? however, I sincerely hope that your hand is now really better, otherwise you won’t be able to smack Auntie Maggie when she deserves it: will you?

Yes thank you Mina, I had a lovely holiday in Yorkshire & Mrs. Backhouse’s people were all so nice to me, Mrs. B. also had a very nice time, they travelled 3,000 miles in fourteen days, but he was unfortunate enough to develop a very severe cold during the last week, & he

Page 3

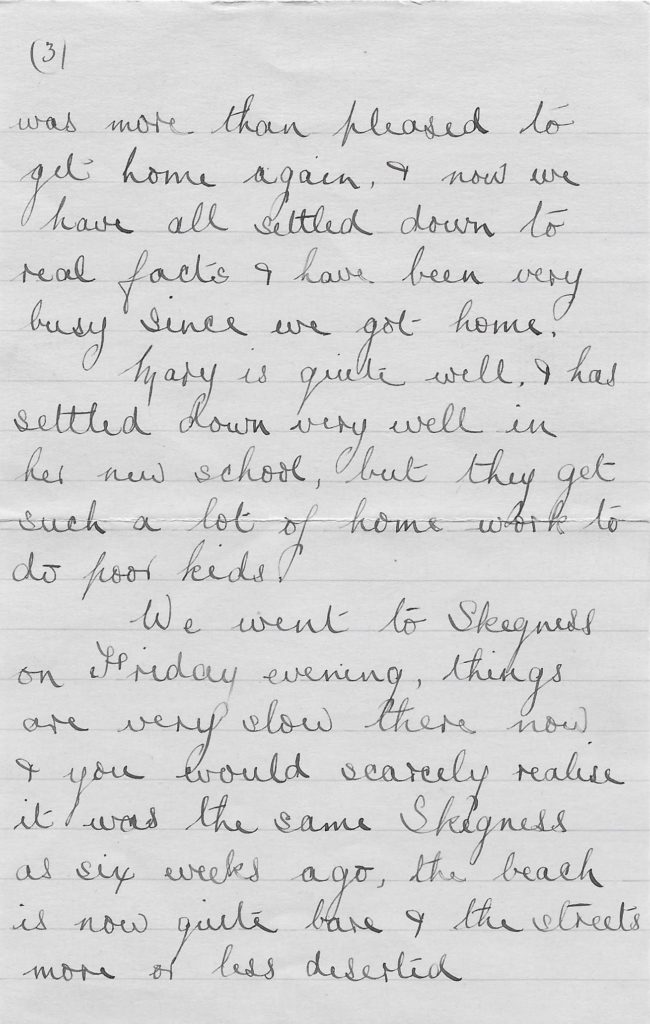

(3)

was more than pleased to get home again, & now we have all settled down to real facts & I have been very busy since we got home,

Mary is quite well, & has settled down very well in her new school, but they get such a lot of home work to do, poor kids!

We went to Skegness on Friday evening, things are very slow there now, & you would scarcely realise it was the same Skegness as six weeks ago, the beach is now quite bare & the streets more or less deserted.

Page 4

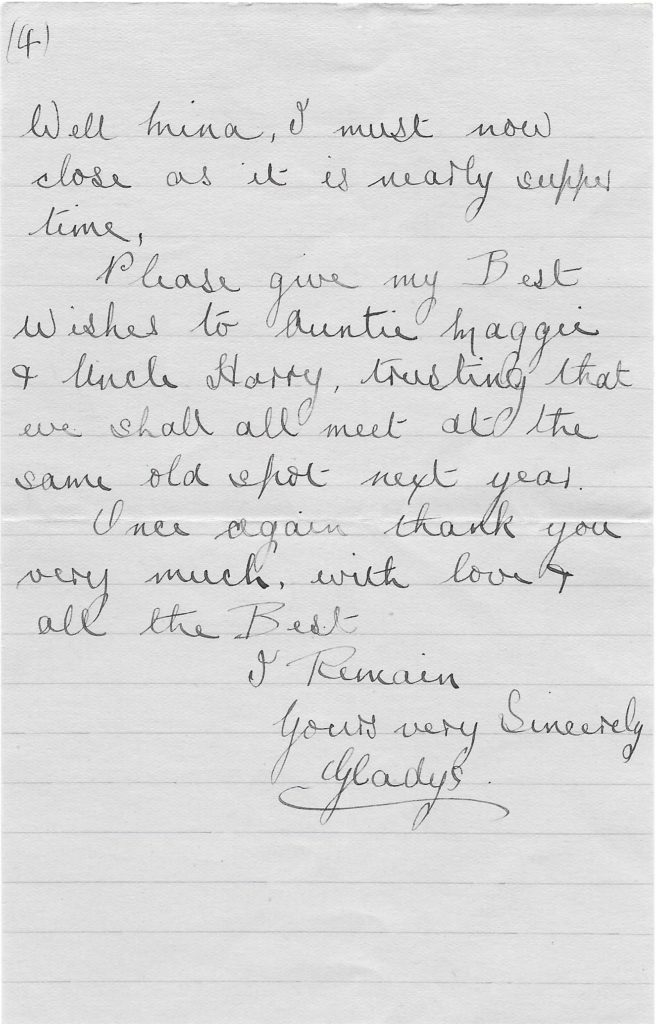

(4)

Well Mina, I must now close as it is nearly supper time,

Please give my Best Wishes to Auntie Maggie & Uncle Harry, trusting that we shall all meet at the same old spot next year,

Once again thank you very much, with love & all the Best

I Remain

Yours very Sincerely

Gladys

Explanation

This letter, sent by Gladys from School House, St Mary, Wainfleet, Lincolnshire, to Mina on 4 October 1937, is a lively and affectionate piece of personal correspondence between friends or close relatives.

Gladys begins by thanking Mina for sending “corn stuff” (likely a home remedy for foot corns), expressing her hope that the treatment will be effective. She shows concern for Mina’s recent fall and jokingly asks what she was up to, hoping her injured hand is healing—otherwise, she teases, Mina won’t be able to “smack Auntie Maggie when she deserves it.”

Gladys then describes her recent holiday in Yorkshire, highlighting the kindness of Mrs. Backhouse’s family. She adds a note about their remarkable travel distance—3,000 miles in fourteen days—and shares that Mrs. Backhouse’s husband suffered a severe cold during the trip, making him more than glad to be home.

Back in Wainfleet, life has resumed its routines: Gladys mentions being very busy, and that Mary is settling well into her new school, though the workload is heavy. Gladys also recounts a recent trip to Skegness, remarking on how the once-busy seaside resort is now nearly deserted as the season ends.

The letter closes with warmth and good humour, sending best wishes to Auntie Maggie and Uncle Harry, and expressing hope they’ll all meet at their favourite spot again next year. Gladys thanks Mina once again for her kindness, signing off with love and all best wishes.

This letter provides a charming window into everyday British life, relationships, and humour in the late 1930s, showing how family news, health concerns, and changing seasons were woven into the fabric of correspondence.

Front/Inside of Card:

This clever little doggie

Brought her puppies all the way,

To wish you lots of Birthday joy

Because you’re TWO to-day!

To my Greatgrandson Jon

From is greatgrandmar

Reverse/Back or Left Panel:

Just a card with best wishes and many happy returns of the day and a Happy Birthday with fondest love

To my Darling Greatgrandson Jon in memory of days of long ago when is father sent me is first card for my Birthday is mother. Had to guide is little hand to rite. Dear Grandmar. Give my love to Grandmar. I am just hanging on nothing. Great love from all to all. Looking forward to seeing you all.

This is our new

Address 41 Crispin St

off Ragsdale. Turne to the left.

Explanation

This is a birthday card sent on 19 January 1940 to a little boy named Jon by his great-grandmother. The printed poem on the card’s front is cheerful and age-appropriate, featuring a playful rhyme about a dog and her puppies, wishing Jon a joyful second birthday. The message is personalized in ink: “To my Greatgrandson Jon From is greatgrandmar.”

On the reverse or left panel, Jon’s great-grandmother writes a heartfelt note. She offers best wishes and loving greetings for his birthday, and reminisces about the past—remembering when Jon’s father (her own child or grandchild) sent her a first birthday card, with his mother’s help guiding his tiny hand. The writing is warm but tinged with age and frailty: she says she is “just hanging on nothing,” but expresses great love for the whole family and looks forward to seeing them all.

She closes by providing their new address—41 Crispin Street, off Ragsdale, with directions—ensuring the family knows where to find her.

This card is both a charming piece of children’s ephemera and a moving testament to intergenerational affection, family history, and continuity, especially poignant given its wartime date.

Letter from “Daddy” to His Child, 18 April 1947

Transcription

Page 1

My dear old Pal,

Have you begun to think that I have forgotten you completely?

I feel that I ought to write to you, but I have been occupied every single minute of spare time painting – or mixing paint ready for next day – right up to bed-time each night.

As I write now (it is 10.45 p.m. on Sunday) I feel just about “browned-off”.

I started about 9.0 am. and, with the exception of dinner and tea times, worked continuously until dark. Then I cleaned up my brushes and cans, put the ladders etc., away and mixed up a tin of paint for tomorrow. After all that, a good wash and my supper, and here I am.

I was very pleased with your letter. It was very nicely written, and good composition too!

I am glad you are having a pleasant time.

Page 2

I know Grandma would do all in her power to make your stay enjoyable.

The weather has been much kinder of late, so I guess you have been out of doors quite a bit. Fresh air and exercise and good food will all do you good.

Glad to hear you are becoming able to handle a ball. Keep on with it. It will exercise and develop your hands and arms – and may come in useful at cricket.

What about the City beating Coventry on Saturday? I wonder if they will get their revenge on Monday with Q.P. Rovers. I’m hoping they will.

No luck this week with the football pool! Still, I’ll keep on trying.

Took a photo of Mummy and Chris in the garden today (dinner-time) while sun was nice and bright.

See you again soon all being well. Lots of love to you and Grandma

from old Daddy.

Explanation

This is a warm, lively letter written by a father (“Daddy”) to his child, dated 18 April 1947. The tone is affectionate and conversational, blending family news, encouragement, and day-to-day details. Daddy apologizes for not writing sooner, explaining he has been busy painting from early morning until bedtime and describes his exhausting day in detail.

He compliments his child’s previous letter, praising the writing and composition, and expresses gladness that his child is enjoying their time away. He is confident that Grandma is making the stay enjoyable and remarks on the good weather, hoping his child is spending time outdoors getting fresh air, exercise, and nourishment.

Daddy encourages his child’s progress at handling a ball, noting its benefits for health and possible future use in cricket. He includes football news—expressing hope that “City” (likely their favourite team) will beat Coventry and do well against Q.P. Rovers, and mentions his own lack of success with the football pool.

A charming domestic note follows: Daddy took a photograph of Mummy and Chris in the garden during a sunny lunch break. The letter closes with affection, wishing love to both the child and Grandma and looking forward to seeing them again soon.

Overall, this letter offers a delightful glimpse of postwar British family life, affection, and routines, marked by humour, sports, and gentle encouragement.

Letter from Mummy to John, 87 Cardinals Walk, Leicester, c. April 1947

Transcription

Page 1

87, Cardinals Walk,

Leicester.

Sun. even.

My dear John,

I was so pleased to receive such a nice letter from you. Really it was the best you have written to anyone for a long time. I do hope it was your own composition & that Grandma didn’t help you too much.

So I thought you deserved another short note from me. We’ve been going along very quietly since I last wrote to you. Mrs. Oram came round to tea on Thursday with Malcolm & the baby who didn’t seem to think much of me! Then on Friday, we had to go over to Grandad’s. He’d had a very nice holiday at Auntie Phyl’s & was quite nicely. I asked him to come over here for the day, today, but he hasn’t turned up. “Not the first time”, did you say?

Page 2

We’ve not done anything this weekend (Chris & I, I mean; Daddy has been painting all the time. You can see your face in the coal-house & lavatory doors!) There doesn’t seem much point in going anywhere without you. I hope the weather will hold good when you come home so that we can go to Bradgate or somewhere like that.

I thought C. wasn’t going to Sunday school but I dressed him up in everything—white blouse, trousers, shoes, socks & promised to meet him out. I did, & we went for a little walk down Brook Road. Course he had to put one foot in the water as we crossed over the stepping stones! Do you remember the paddling spot where we used to picnic when Elizabeth was here?!

Page 3

I wondered if Mrs. Oram might go with us tomorrow or Tuesday.

We shall probably come up before dinner on Wednesday. I’ll bring something extra if Grandma does plenty of potatoes. Then you can do a bit of wireless with Chris. He could understand better what was on his note than I could!

So glad your bouncing is making good progress. I wish you could do it without catching each time—just keep on bouncing. And keep on roller-skating.

What a shame about the wireless accumulator. I suppose you haven’t had a sound all week. Two would certainly be a very good idea. I can’t imagine what we should do here without it. Course we managed without at Mablethorpe, didn’t we? But there’s one good thing about it, I don’t suppose you make getting ready for bed quite such a lengthy business!

Page 4

I haven’t heard from Auntie Davenport yet, but we shall in a day or two. Is your blazer badge still nice & clean? She’ll want to see you dressed up. I haven’t got far with your shirts. Oh dear!

Hope you can read this pencil scrawl. Am writing on my knee. Be good to Grandma. She’s so kind to you.

Much love to you both,

Mummy.

Explanation

This is a loving, conversational family letter written by “Mummy” to her son John, who is apparently staying with his grandmother (and possibly his sibling Chris). It’s written from 87 Cardinals Walk, Leicester, on a Sunday evening, probably April 1947 (matching the date from the father’s letter in your earlier upload).

Mummy opens with praise for John’s previous letter, saying it was the best he’s written “for a long time,” and playfully hoping Grandma didn’t help too much. She gives a brief account of a quiet week: a visit from Mrs. Oram and her children, a trip to Grandad’s (who enjoyed a holiday at Auntie Phyl’s), and attempts to get Grandad to visit—which haven’t worked out.

The letter is full of domestic details and affectionate teasing. She reports that Daddy has been busy painting, making the coal-house and lavatory doors so clean “you can see your face” in them. She laments that outings seem pointless without John, and hopes the weather will be good so they can visit Bradgate (a local beauty spot) when he returns.

She describes getting Chris dressed up for Sunday school, a walk that ended (as usual) with him stepping into water, and reminisces about their old paddling spot and picnics with Elizabeth. Plans are made for visits and future outings.

Mummy also mentions John’s progress with “bouncing” (possibly a toy or physical activity) and encourages him to persist, also mentioning roller-skating. She laments the loss of sound from the “wireless accumulator” (a battery for their radio), saying two would be ideal, and jokes that at least it makes bedtime less drawn-out.

The letter closes with practical matters (washing shirts, blazer badge), a gentle reminder to be good to Grandma, and a loving sign-off.

In summary:

This letter is a warm window into postwar British family life, showing the affectionate, sometimes humorous, often logistical correspondence between parent and child—full of the small events and concerns that bind families together.

Letter from Mummy to John, 87 Cardinals Walk, Leicester, Friday [circa April 1947]

Transcription

Page 1

87, Cardinals Walk

Leicester.

Friday.

My dear John,

I do hope you are having a nice time. ‘Fraid the weather hasn’t been quite so good but anyway, it’s fine.

Uncle Davenport wants to take us for a ride on Monday. He’s calling for us at 10.30 a.m. so how would it be if we call up for you soon after that? It will cut your holiday a bit shorter, but Auntie does want you to come with us. I’m going to pack up lunch & then we shall get none for tea.

Page 2

It would be an easy way of getting you home, wouldn’t it? I suggest you pack up your things after dressing on Monday morning (put on your best shirt) & then the case could go in the car. Hope grandma won’t mind you coming away a bit earlier than we’d thought.

Let’s hope it’s a lovely day, but weather wasn’t mentioned so expect us in any case.

Much love to you both

Mummy.

Explanation

This brief and affectionate letter, written by “Mummy” from 87 Cardinals Walk, Leicester, is addressed to her son John (and possibly another child, Chris). It is dated simply as “Friday,” but internal references and handwriting match other letters in the family archive from April 1947.

Mummy expresses hope that John is enjoying his holiday, even though the weather hasn’t always been ideal. She explains that Uncle Davenport is planning to take the family for a ride on Monday and will collect them at 10:30 a.m. She suggests they could pick John up soon after, even though this means his holiday will end a little earlier than planned, emphasizing that Auntie is keen for John to join them. Mummy adds a practical note: she will pack lunch for the outing, but warns there will be nothing left for tea!

She proposes John pack his things after getting dressed on Monday morning (reminding him to wear his best shirt), so his suitcase can go in the car. She gently hopes Grandma won’t mind him leaving a bit sooner than expected.

Mummy closes with well-wishes, reminding John (and presumably Chris) that, rain or shine, they should expect to see her. The letter is signed simply, “Much love to you both, Mummy.”

Summary:

This letter is a classic example of caring, logistical family correspondence—balancing plans, practicalities, and feelings. It reflects the close bonds and gentle negotiations typical in postwar British family life, where arrangements, visits, and even departures were coordinated with affection and a sense of consideration for everyone involved.

Letter from Valerie to John, 15 Oakfield Ave, Glenfield, Leics – 23 June 1954

Transcription

15, Oakfield Ave,

Glenfield,

Leics.

June 23rd.

Dear John,

We were very sorry to hear that you are back in hospital. At school next week we have exams. (worse luck!) I’m dreading them, especially (is that spelling correct) history and geography. They’re my worst subjects. I have been swatting quite a lot this week.

I am writing this after going to the swimming baths. I can’t quite swim yet. I like the sea much better than the baths, and seem to keep afloat more!!

Last Sunday we went to Christopher Simpson’s christening (John & Pat’s baby). Mummy & Daddy were godparents.

We had a lovely time. Tomorrow it’s the sports at the Frith where Mummy works. She says it’s ever so funny to see the children run.

By the way, have you still got your tortoise? Ours is still thriving. We still have 1 fish as well. We did have 3 but the other two have died.

Well, I must close now

Love

Valerie

xxxx

P.S. Please excuse writing. I hurried to catch the post and then missed it!

Explanation

This is a cheerful and newsy letter sent by Valerie, a young girl living at 15 Oakfield Ave, Glenfield, Leicester, to her friend or relative John, dated June 23rd, 1954. The letter was written after she heard John was back in hospital, and its warm, conversational tone is typical of a friendly letter between children or young teens in the mid-20th century.

Valerie opens with sympathy for John’s situation, then shares a bit of school anxiety: she has exams coming up, is dreading them (especially history and geography), and has been studying hard (“swatting”). She writes just after a trip to the swimming baths, noting that she can’t quite swim yet but prefers the sea to the baths and can keep afloat better there.

She recounts a recent family event: attending the christening of Christopher Simpson, where her parents were godparents. She mentions an upcoming school sports day at “the Frith” where her mother works, adding a child’s view on the fun of watching other children run.

Valerie then asks after John’s tortoise, reporting that hers is “still thriving,” and notes that, although they had three fish, two have died.

The letter ends affectionately, with “Love, Valerie” and four kisses, plus a postscript apologising for her handwriting—she hurried to catch the post, but missed it.

Summary:

This letter offers a snapshot of the daily life, worries, and joys of a British schoolgirl in 1954. It reflects a close, friendly relationship, full of small details about school, home, and pets, and provides a charming glimpse into mid-century childhood correspondence.

Letter from Father to Son in Hospital – 23 St. Winifred’s Avenue, Luton, Beds, 24 June 1954

Full Transcription:

23, St. Winifred’s Avenue,

Luton,

Beds

24/6/54

My dear John,

Although I cannot come to see you this week, owing to my being obliged to be working there, I would like you to know that I am constantly thinking of you and hoping you are progressing.

My dear Son, please bear in mind what I told you in our rather serious talk just before you came back to hospital – I am your pal to whom you can always turn. No matter what the trouble is, you may trust me to share it with you.

Please try to continue to bear your misfortune with patience and manliness. You have already shown that you are a man and I am proud to own you as my son.

Don’t think I am preaching at you. I don’t want to do that! Just talking very earnestly, that’s all.

I’ve had a rather hot and mushy day today – trying to get plenty done so as to be back in time for the “leg-man” on Friday evening.

By the way, my Luton photographic friend, who gave me the tripod, has made a smashing enlarger. Apart from the lens it cost him about 50/- to £3.

He uses moulded glass condensers and an opal bulb and the lighting is as even as you could wish! (So much for optical condensers!) The lamp house is a big cylindrical jam tin (with page) and the focusing is by a set of old camera bellows (2/6d)!

Shall we have a go as soon as you come out again? Incidentally, he leaves bargain price ex W.D. printing paper at 6/6d a gross – size about 6” square. Quite satisfactory if not glazed too highly! This is nearly as cheap as contact-paper 2¼ size!

What do you think of Chris’s first adventure into the art? Did Mummy tell you? When he went to Bradgate he blew off 7 exposures of HP3V at one smack. I don’t know what they’ll be like but hope he will have had beginner’s luck at least.

I really must get cracking on both yours and Chris’s at first chance to see what the results are like. It’s a pity about my having to be away this week, but blister shock next perhaps.

Well, although I’ve headed this letter with my lodging address, I’ve really written between stores jobs at the garage.

The next man requiring my attentions will be in any minute now I guess, so I must begin to draw it as graceful a conclusion as possible.

It’s a matter of fact here it is! and a mucky old job it is to do.

Ah well here goes.

Please excuse patchy writing (I haven’t my glasses with me for one thing and I’m holding the paper on my knee for another).

God bless you and keep you in His safe keeping, my dear old Topper – always

Your loving old Daddy.

P.S. Will be seeing you on Saturday all being well.

Keep cracking!

Explanation:

This is a heartfelt letter from a father to his son John, who is in hospital. The father expresses regret that he cannot visit John that week due to work commitments, but reassures his son that he is always thinking about him. The tone is warm and encouraging, reminding John to face his challenges with patience and manliness, and reiterating the closeness and trust between them.

The father updates John on everyday life, including a photographic project, the achievements of Chris (presumably John’s brother), and his own busy work schedule. He talks in detail about a friend’s homemade photographic enlarger and mentions the hope of working on some photography with John once he’s out of hospital.

The letter is conversational and personal, blending ordinary updates with affectionate advice and reassurance. The father closes with blessings, a note about the writing conditions, and a promise to see John soon, reinforcing his ongoing support and love.

In summary:

This letter is both a window into mid-20th century family life and a touching example of paternal support during a time of illness or convalescence. It highlights the importance of communication, encouragement, and shared interests in maintaining a strong parent-child bond, even during difficult periods apart.

Letter to John in Hospital from Gill, Glenfield, Leicester – Tuesday, July 6, 1954

Full Transcription

Page 1:

15, Oakfield Avenue,

Glenfield,

Leicester.

Tuesday

Dear John,

We were very sorry to hear that you have had to return to hospital, and we do hope that you will be home again soon. I suppose you must be feeling very fed up, but we can only hope that soon you’ll be alright again. It is most boring at school nowadays as everyone seems to have completely stopped work. Several trips have been planned however & this afternoon Bishop Maxwell came to speak to us. We are also having the film of Everest shown to us. A party went down a coal mine this morning, but to tell you the truth, although I should love to see what it is like down there, I really don’t like the idea of going all that way down in a cage—a lift is bad enough!! The sixth form are going on an outing to Greettham Gardens for the day next Tuesday, and afterwards we intend to go

Page 2:

to a play at a theatre in Derby. On Friday a trip to Oxford has been planned & also a visit to Chatsworth House one day in the week. A week on Friday the choirs of the school are giving a concert. The Bennett family will be well represented as all three of us are taking part. It should be a success because all the songs seem to be going on nicely. I took Maths in the G.C.E. but I really don’t think that I shall pass even though I could do quite a lot on the paper!! (Surprise!!!)

Mummy & Daddy have been very busy lately catching newts from the pond!!! Instead of fishing for them with a fishing net, a piece of string with a pin and worm on the end has been employed!! They have caught at least 20 & we hope that we shall clear them out for good if possible & then we can have some goldfish at last.

Valerie & Jack have both

Page 3:

finished their terminal exams (much to their relief). Both seem to have done fairly well, & I expect their reports will be very good as usual.

Well, I must close now, or I shall miss the post.

Get better as soon as possible,

Love from

Gill

Explanation

Context & Meaning:

-

This is a personal letter from a young woman named Gill to John, who is currently in hospital, written from her family home in Glenfield, Leicester, in early July 1954.

-

Gill expresses sympathy that John has had to return to hospital, and hopes for his quick recovery.

-

She updates him about life at school: work has mostly stopped for the term, but a number of events and outings are planned, such as visits from speakers, a film showing, a trip to a coal mine, a concert, and other excursions.

-

Gill admits to anxiety about her maths GCE exam, not expecting to pass despite being able to answer much of the paper.

-

There is a light-hearted section about her parents catching newts from the garden pond with an improvised method, hoping to eventually have goldfish.

-

She also reports that Valerie and Jack (presumably siblings or cousins) have finished their end-of-term exams and did well.

-

The tone is friendly, warm, and supportive, intended to cheer John up during his hospital stay and keep him informed of family and school news.

Historical/Social Insight:

-

The letter gives a charming snapshot of British family and school life in the 1950s, with references to common events of the time: end-of-term exams, grammar school outings, and the General Certificate of Education.

-

The casual, conversational style and inclusion of little family details (like the newt-catching!) show the affectionate nature of family correspondence.

-

The fact that schoolwork has “completely stopped” at the end of term but activities and trips continue is a familiar experience for many students, then as now.

Summary Caption:

“Letter from Gill to John, July 1954: School summer term winds down with concerts and outings, family life includes quirky newt-catching, and warm wishes for a speedy recovery are sent to a young relative in hospital.”

M

194

I had got a splinter of bone stuck in my throat, and had to have an operation to get it out on Thursday morning. I am about alright again, but I shall be very careful in future, to search my meat, for any splinters of bone.

Hope you well soon be home again

Yours Sincerely

Geo Thompson

Explanation:

This is a business letter, written on headed paper from Geo. Thompson, a stamp dealer based at 76-78 Belgrave Gate, Leicester, to a young customer, Master John Marlow, on July 20, 1954.

-

Content Summary:

The letter acknowledges surprise and pleasure at receiving John’s letter. Geo. Thompson wishes John well during his stay in the “R. I.” (Royal Infirmary—suggesting John was in hospital), and promises to set aside a “complete set of the Royal Town” stamps for him at the price of 8 shillings. Thompson then shares a personal anecdote: he too was recently in the Royal Infirmary, staying in Oliver Ward after an operation to remove a bone splinter from his throat. He advises caution when eating meat in the future. -

Context:

-

The letter blends business (stamp collecting) with personal well-wishing, typical of friendly small business relationships of the era.

-

The mention of hospital stays on both sides reflects a sense of mutual empathy and care.

-

The set aside “Royal Town” stamps would have been a desirable collector’s item.

-

The personal note about the operation adds warmth and humanity to what otherwise could be a strictly commercial exchange.

-

-

Historical interest:

This letter gives a window into mid-20th-century stamp collecting, customer relations, and the personal touch that often characterized small businesses at the time. It also illustrates the norms of written communication and the intertwining of personal and professional lives in correspondence.

Letter from 75 Princess Road, Leicester – Holiday in France, Accidents and Anecdotes (Term 17th, 1954)

Transcription in Full:

Page 1:

TELEPHONE

LEICESTER GRANBY 2961.

75 PRINCESS ROAD,

LEICESTER.

Term. 17th.

Dear John

Back at last – arrived on Sunday night 11–30pm.

Had a grand time – now speak french like asphalt arab.

Hope you received my card from somewhere in France & one from Paris. The Paris one I expect amused you – did you like the view of the Eifel Tower & the curvacious blonde in the foreground?

Page 2:

If you would like me to come in any evening and give you a description of the holiday – I will.

We had no serious accidents apart from hitting 4 cars 1 motor bike & 1 pedestrian – and I am not pulling your leg for we actually did. I myself hit 2 cars – a citroën & a renalt.

The weather was gorgeous. The wine & food very good.

Hope you are getting better & can return next term. Give my love to the nurses.

All the best Johnny.

Everything Explained:

This playful letter comes from Johnny, writing to his friend John from 75 Princess Road, Leicester, soon after returning from a holiday in France, dated “Term. 17th.” Judging by content, the year is 1954, and John is likely in hospital or recovering, as Johnny closes with good wishes for his health and greetings to the nurses.

Key details:

-

Travel Recap: Johnny reports arriving back late Sunday after a French trip, boasting that he now “speaks French like asphalt Arab” (a humorous, self-deprecating claim).

-

Postcards: Johnny mentions sending John a card from France and one from Paris, referencing a humorous postcard of the Eiffel Tower with a “curvacious blonde in the foreground.”

-

Holiday Incidents: With typical British understatement, Johnny says there were “no serious accidents apart from hitting 4 cars, 1 motor bike & 1 pedestrian,” then clarifies “I am not pulling your leg for we actually did. I myself hit 2 cars – a citroën & a renalt.” This comic exaggeration highlights the chaotic adventures of the trip.

-

General Impressions: The weather and food were excellent, wine enjoyed, and Johnny offers to describe the holiday in person.

-

Kind Wishes: He closes by wishing John a good recovery and return next term, sending regards to the nurses.

Summary:

This letter is a warm, humorous travel note, vividly illustrating the carefree, slightly chaotic, and sociable spirit of postwar British youth, mixing travel tales, gentle teasing, and genuine concern for a friend’s recovery. The mention of accidents is comedic and not meant to shock, serving as light-hearted banter. The closing shows a kind regard and a promise to share more stories in person.

Letter from Sid Wilby, Ward 5, General Hospital, Leicester, to John — 22 March 1955

Page 1:

Ward 5

General Hospital

Leicester

Mon.

Dear John,

It was delightful to hear from you. Naturally, I have not forgotten our association together and I think of you often. That St. Margaret’s have not heard from me direct is quite true for a very good reason. I have had no proper definite news to give them.

Page 2:

I came here for a spinal graft, which I had last Nov[ember] & I am still undergoing the period of rest required after this operation. That I have been up for a little during the last fortnight is quite a change but the progress is very slow and it will be some time before real confidence can be assured. This is a nice hospital in many ways & we have varied entertainment and

Page 3:

television. Cinema shows are on Monday nights when some of the well-known & quite good films are shown – also wireless & sometimes quite a spate of gramophone recording machines. It gets a trifle too much on occasion. The routine is generally the same, bar [illegible, possibly “skipping”] as watching bedmaking, strict routine, but one gets used to most things & does. Hospitals become tolerable.

Page 4:

The weather is improving by the look of things & about time too – so perhaps we shall all be able to appreciate brighter & more cheerful times in the near future.

I am extremely pleased to hear that you are making headway & are you doing any studying now? One has you let that rest for a little while – whatever you are doing I hope it will be good for you.

Page 5:

My mother comes to visit me quite regularly & many friends drop in at nights from time to time and so the passing of the months goes quickly – in fact it seems incredible when I look back to think I have been nearly 16 months in bed or practically so for most of the time! It is now 12 ½ st from the rattle of pots. I really trust the usual midday meals move on this rotory [sic] low record.

Page 6:

Best wishes to your mother & father, not forgetting kindest regards for yourself.

Sincerely,

Sid Wilby

Explanation:

This is a personal letter written by Sid Wilby from Ward 5 of the General Hospital in Leicester, dated around March 1955 (the day isn’t written, but internal file names say “22 March 1955”). The recipient is “John.” Sid shares news about his long hospital stay following a spinal graft operation the previous November and describes the slow recovery and monotonous but bearable life in hospital. He mentions entertainment provided to patients (television, films, wireless radio, gramophone records), visits from his mother and friends, and routine hospital experiences.

The tone is warm, resilient, and maintains a sense of humour despite the lengthy confinement (“it seems incredible… nearly 16 months in bed or practically so for most of the time!”). Sid expresses pleasure at John’s progress and sends his best wishes to John’s parents.

The letter is a vivid glimpse into postwar NHS hospital life and the importance of friendship, routine, and small comforts in long-term recovery. It also subtly highlights the persistence of optimism and connection despite personal adversity.

Letter from [Signature unclear, possibly “W. Carter”], 34 Lewis Road, Kettering, Northants, to John — 10th January, 1956

Page 1

34 LEWIS ROAD,

KETTERING,

NORTHANTS.

10th January, 1956.

Dear John,

It was extremely nice seeing you in St. Margaret Ward, but not as a fellow patient this time. It was a treat to find you looking so well and from your very fit appearance you haven’t got a possible chance of getting in as a patient again. Your company for a few weeks would have been most welcome but I am pleased to say that I am back home again now, having come out last Tuesday. I have to go over to see Dr. Englander on Wednesday and expect there will be the usual periodic visits so that it is just possible I may see you from time to time. Only a few days before you looked in Dr. Englander spoke to me about you and said how well you were keeping.

I really have two of your letters to answer and I would have written some time ago had I not been laid low. Most of the points I think we chatted about when you were in the Ward.

Having no dark room facilities at my present address I feel I shall not be doing a great deal of photography unless going in for a bit of colour film, which I would not have to process myself and which would merely require mounting as slides. This however would call for a projector and at the moment I am not really sufficiently interested to go in for one. However, with the Spring and Summer before us I may change my mind and if sufficient energy is forthcoming quite likely I shall fetch the camera out again.

Page 2

The really interesting part that I always find is the enlarging but here I am beaten for facilities unless I go to quite a lot of trouble to black out my small kitchen or, alternatively, the bathroom. With the latter however there is neither the room nor the electric points.

Your effort at enlarging was particularly good and I am sure Nurse Yates would have been very pleased with the result. Strange to say, although I took several snaps of her I never got a really good result.

I did not go in for the Wrayflex. As you know, I seriously considered it but after all decided against going back to 35.mm size. What I would like would be the Hasselblad with two or three lens and the interchangeable backs so that I could use one for colour and one for black and white. This camera though I am afraid must remain a dream as the price is far and away beyond my pocket.

I had a letter this morning from Mr. Wilby. He is getting about a little now but is not 100% active, although I gather he is doing part time at work.

With the Ward news you are doubtless au fait except possibly on one item – just as I was leaving last Tuesday morning Sister Smith said she was leaving at the end of the month. Just what happened I do not know but I gather it was a very sudden decision. I wonder who will take her place.

No other news that I can think of at the moment so with very kind regards to Mr. & Mrs. Marlow and yourself, and with every good wish for 1956,

Yours sincerely

W. Carter

Explanation:

This letter was sent from W. Carter (address: 34 Lewis Road, Kettering, Northants) to John on January 10, 1956. The letter is warm and familiar, referencing a recent meeting in St. Margaret Ward (presumably a hospital ward), where John is apparently recovering well. Carter reports his own return home and provides updates on his health, follow-up medical visits, and his ongoing interest in photography—though noting the lack of facilities for developing and enlarging prints at his current address. There is technical discussion about film types (mentioning colour slides, the Wrayflex camera, and a wish for a Hasselblad with interchangeable lenses/backs).

Carter also refers to mutual acquaintances, notably Mr. Wilby, who is recovering and partially back to work, and mentions Sister Smith’s sudden decision to leave her post at the ward.

The tone is friendly, slightly humorous (joking about John’s unlikelihood of returning as a patient), and rich with details of daily post-hospital life and the social connections between former patients and staff. The letter ends with seasonal good wishes and regards to John and the Marlow family.

Letter from Roger Burkett, 56 Edward Avenue, Narborough Road South, Leicester, to John — [Date not specified, 1950s]

Full Transcript (Norwegian original and English translation):

Header (top left):

School/College crest with Latin motto: “Scientia et Virtus”

Address (top right):

56 Edward Avenue

Narborough Road S.

Leicester

Text:

Kjære John,

Mange takk for deres brevkort!

Det var synd, jeg sådte ikke fotograf’n av A.L.T domkirke-n ved Wells!

Nei fangen!

Med de beste ønsker for Nottingham, også London for meg!!

Deres forbundne,

Roger Burkett.

English Translation:

Dear John,

Many thanks for your postcard!

What a pity, I did not see the photograph of A.L.T cathedral at Wells!

No luck!

With best wishes for Nottingham, and also London for me!!

Yours sincerely,

Roger Burkett.

Explanation:

This is a brief, friendly note in Norwegian from Roger Burkett to John, written from Leicester. Roger thanks John for a postcard and regrets not having seen a particular photograph of (apparently) the A.L.T cathedral near Wells. He expresses disappointment (“No luck!”) and sends best wishes for Nottingham—and for London on his own behalf. The closing (“Deres forbundne”) is a slightly formal, almost old-fashioned way of saying “Yours sincerely” or “Yours faithfully.”

The letter is informal, with a touch of good-natured banter, and it highlights a shared interest in travel or photography—likely linked to their mutual experiences in England. The presence of Norwegian suggests one or both had connections to Norway, or perhaps were practicing the language together. There’s no date, but the style and context place it mid-20th century, in the 1950s.

Letter from Rev. P. J. Baxter, 21 South Street, Stanground, Peterborough, to John — 25 October [1956]

REV. P. J. BAXTER.

21, SOUTH STREET,

STANGROUND,

PETERBOROUGH.

OCTOBER 25th.

Page 1:

Dear John,

It was good of you to write to me and say how sorry you were Dad had died. I only hope that my delay in answering has not made you think it was not appreciated, because it was — very much so.

I expect you know better than I how much Dad went through. Although he meant a great deal to many besides me, I think the common feeling is that the Lord had was very merciful

Page 2:

in sparing him further pain. I could not wish him longer in this world if the price demanded was so much suffering.

I hope you are enjoying life, & that the course goes well. I often wonder what you are doing — back at school, I expect. Whatever it is, you have my best wishes, & hopes of success & happiness.

Yours sincerely,

Paul Baxter

Explanation:

This is a heartfelt condolence acknowledgment from Rev. Paul J. Baxter to John, written on 25 October (year not given, but context suggests 1956). The letter thanks John for writing after the death of Rev. Baxter’s father, apologizing for the delayed response due to mourning. Baxter expresses deep gratitude for the sympathy and shares a sense of relief that his father’s suffering was not prolonged, seeing this as an act of mercy.

He goes on to express hope that John is doing well, possibly back at school, and wishes him success and happiness in whatever he does. The letter is personal, warm, and reflective, with a strong sense of faith and gratitude for friendship and support during a difficult time.

Letter from David, 20 Sweetbriar Rd., Leicester, to John — [mid-April, likely 1957]

Page 1

20, Sweetbriar Rd.

Leicester

Dear John,

Thank you for your greetings on my birthday.

I’m pleased to hear you have accepted a place at Leeds.

Everything is ‘all right’ in architecture!

I’m sorry but I’m going to Manchester on Friday, Lincoln on the following Tuesday, returning the day before we go back to college.

Page 2

Until Friday I am going to Coventry one day and completing notes and drawing for next term.

An architect’s job is never done!

You will be twenty soon won’t you?

What an age! 2-0-

Many happy returns on the great day

Yours

David

Explanation:

This is a friendly, informal letter from David in Leicester to John. David thanks John for his birthday greetings and expresses happiness that John has accepted a university place at Leeds. David gives a brief update about his own busy schedule studying architecture—mentioning trips to Manchester, Lincoln, and Coventry, and the endless workload of notes and drawings.

He then notes that John’s twentieth birthday is approaching, expresses surprise at “what an age!” (twenty), and wishes him “many happy returns” on the great day. The tone is cheerful, supportive, and shows the warmth of young adult friendship, sharing both the realities of their busy student lives and genuine good wishes.

Letter from G.F. & H.H. Dicey, 58 Cardinals Walk, to John — [Date unknown]

58 Cardinals Walk

Dear John,

There is a little surprise for you, we do hope you will enjoy the contents.

How are you?! We are thinking of you, & hope to see you again soon.

Goodnight, God bless, & sleep well.

G.F. & H.H. Dicey

Explanation:

This short, affectionate note comes from G.F. and H.H. Dicey at 58 Cardinals Walk, addressed to John. The writers mention that they have sent John “a little surprise” and hope he will enjoy whatever is included (possibly a small gift or treat). They express care and concern, asking after John’s well-being, letting him know he is in their thoughts, and expressing hope to see him soon. The letter closes with warm wishes for the night, invoking both blessings and comfort.

The tone is gentle and nurturing, likely from older relatives or family friends. The lack of a date, and the informal, bedtime tone, suggest it may have accompanied a parcel or bedtime gift.

Letter from “Daddy” to his son — [Date unknown, likely 1950s]

Full Transcript:

Dear old Son,

I thought I would like to write you a note as I shan’t be seeing you tonight. Of course I haven’t anything to write about really, but I want you to know that I am thinking about you all the time, and looking forward to the day when you will be home with as much eagerness as you must also doing.

I haven’t made an enlarger yet – but am studying form. The lens is the “Spoldensf.” I can’t afford to buy a posh lens and it seems foolish to use a poor one and thus negative all the good work of a decent lens in the camera.

However I shall perhaps pick up a Tessar or something for a mere song if I wait long enough! Or what do you think?

I am sending this week’s “A.P.” although I haven’t shamefully gone through it myself – but I know you must be eager to see it.

God bless you my dear son, you are constantly in my thoughts (and prayers). Night-night!

Your loving Daddy.

Explanation:

This letter is a gentle, affectionate note from a father (“Daddy”) to his son, written on a night when he won’t see him in person. The father writes simply to let his son know he is always thinking about him and eagerly awaiting his return home. There’s discussion of camera equipment—specifically, about not having made a photographic enlarger yet, the merits of different lenses, and the financial wisdom of waiting for a good lens (perhaps a Tessar) rather than settling for a poor one.

He includes a mention of sending the week’s issue of “A.P.” (likely Amateur Photographer magazine), even though he hasn’t read it yet himself, knowing his son would be eager for it. The letter closes with heartfelt well wishes and the reassurance that the son is always in his father’s thoughts and prayers. The tone is warm, personal, and quietly loving—typical of close family correspondence in the mid-20th century.

Letter to Ennia [date unknown, sender not named]

Full Transcript:

Dear Ennia,

I am sending you this blouse. I think I have made it big enough but this pattern always makes goods look bigger than what they really are, but I ride must-abide. It may possibly run up in the wash.

Enclosed you will find two S.2 P.O.

S.2. for your little self; S1 for Eric & I owe your

Mother one, pay it—for me. There’s a good girl.

I hope you will have a Happy Xmas & a Bright New Year.

Your loving

Auntie

Explanation:

Here, “Auntie” asks Ennia to pay her mother one of the enclosed amounts, kindly instructing “There’s a good girl.” She then offers warm holiday wishes—hoping Ennia will have a happy Christmas and a bright New Year—before signing off as “Your loving Auntie.”

The letter as a whole is personal, affectionate, and practical, containing both material support and heartfelt family warmth, probably written in the early to mid-20th century. The reference to postal orders and the familiar sign-off reflect a time when handwritten notes and small gifts were common tokens of care across generations.

Letter from Loving Dad to “Old Son” — [Date unknown, likely mid-20th century]

Dear Old Son,

I have managed to obtain (from Kittler’s) a pair of odd “clips.” Please take reasonable care of them, as they were a ridiculous price for what they are — in my opinion. However, you are welcome to them.

I thought the light one would do for holding the film at top and the heavier one would keep it down at bottom.

Enclosed also are a few oddments which may be handy to rig up something to hang the film upon.

Now serious for the present. I shall be thinking of you my dear boy. Don’t forget 10.30 p.m.! I take this very seriously and believe that much can come from it.

God bless you always.

Loving Dad.

Explanation:

This letter is a caring, practical note from a father to his son. The father sends his son a pair of “odd clips” (purchased from a shop called Kittler’s), mentioning their cost but gladly gifting them. He gives thoughtful advice on how to use the clips for holding film (likely photographic film) and includes a few extra items for hanging the film.

The letter closes with affectionate encouragement and a reminder to remember something significant at 10:30 p.m., which the father takes very seriously (possibly referring to a daily prayer, routine, or moment of connection). The letter concludes with a blessing and signature, “Loving Dad,” reflecting deep parental care and attention to both practical and emotional needs.

The Family Letters Archive: A Window into 20th Century British Life, Love, and Endurance

Introduction

The archive of letters examined in these conversations constitutes far more than a collection of old correspondence. These are living documents, written primarily from the late 1940s through the 1950s, that offer a unique, authentic insight into British domestic life, family bonds, illness and recovery, and everyday concerns during a period of profound social transition. Through these letters, we see not only the ways people communicated and cared for each other, but also the texture of daily life, the importance of ritual and faith, and the subtle negotiation of hope and hardship.

Core Themes in the Letters

1. Enduring Family Bonds and Everyday Affection

Across the letters, a remarkable warmth and constancy of affection are evident. Whether from “Loving Dad,” “Auntie,” or family friends, the tone is often gently instructional, protective, and loving. Parents and elders encourage, advise, and sometimes send small gifts—blouses, postal orders, or useful odds and ends like “clips” for photographic work. Even in their brevity, these gestures communicate a deep, enduring concern for the recipient’s well-being.

The signature lines—Your loving Daddy, Your loving Auntie, God bless you always—are not perfunctory, but pulse with genuine feeling. They reflect a culture in which open expression of care, often couched in practical advice or tangible support, was a key part of maintaining family unity, particularly during times of separation or adversity.

2. Sickness, Recovery, and the Postwar NHS Experience

Many letters reference illness or convalescence, providing vivid glimpses into the experience of hospitalisation in the early years of the NHS. The correspondence from Sid Wilby (General Hospital, Leicester), W. Carter (Kettering), and others capture both the monotony and small pleasures of ward life—cinema nights, wireless broadcasts, and the routines of patient care.

There is a stoic resilience evident in these narratives, but also a strong sense of community among patients, nurses, and families. Updates on health, progress, or the departure of a favourite nurse (e.g., Sister Smith) are treated as news of communal interest. The letters are full of mutual encouragement and concern, with friends and family tracking each other’s recoveries as a shared endeavour.

3. Ritual, Faith, and Emotional Support

Religious faith is an undercurrent in many of the letters, sometimes overtly—God bless you always; constantly in my thoughts and prayers; or Rev. P.J. Baxter’s reflections on death and mercy. Prayer and ritual (such as the mysterious reference to “Don’t forget 10.30 p.m.!”) serve as sources of comfort and a means of maintaining connection across distance and adversity.

This spiritual dimension is never overbearing, but quietly present. It echoes the wider mid-century British sensibility, in which faith provided structure and meaning, particularly during illness or bereavement.

4. Material Realities and Everyday Economy

The letters provide numerous references to the domestic economy of postwar Britain. Whether it’s the cost of a photographic lens (“a ridiculous price for what they are”), the careful making and remaking of clothes, or the sending of shilling postal orders for “your little self,” there is a pervasive thriftiness and resourcefulness.

Homemade gifts, repurposed items, and small cash presents are tokens of care, but also reminders of the constraints of the time—rationing had only recently ended, and most families still managed with limited means. This context adds poignancy to the gifts and the gratitude with which they are received.

5. Youthful Aspiration and Social Mobility

Several letters, particularly those addressed to John, David, or Ennia, reference educational progress, university placements (e.g., at Leeds), or career milestones in architecture or other fields. The tone is one of pride and encouragement—pleased to hear you have accepted a place at Leeds—mixed with the realities of hard work and long hours—an architect’s job is never done!

These glimpses underscore the rising aspirations of the postwar generation, for whom education and professional achievement were both possible and highly valued. The pride in these milestones is palpable, reflecting changing social attitudes and opportunities in mid-century Britain.

6. Photography and the Pursuit of Hobbies

Another motif running through the correspondence is the discussion of photography—enlargers, lenses, camera models, and the technical and economic barriers to pursuing such hobbies. Whether bemoaning the cost of a Hasselblad or making do with “odd clips” to hang film, these passages speak to the importance of hobbies and the sharing of interests within families.

Photography in particular was a modern, creative pursuit, offering both personal satisfaction and a way to connect with distant loved ones through images. The sharing of Amateur Photographer magazines and advice on darkroom techniques is as much about maintaining connection as it is about the hobby itself.

7. Friendship, Community, and Kindness

Not all the letters are strictly familial. Notes from friends, fellow patients, or ministers (e.g., Rev. Baxter) offer another dimension—the importance of social ties, empathy, and mutual support beyond the nuclear family. These friendships are reinforced by visits, letters, and small acts of kindness, often in response to illness, bereavement, or major life events.

The Value of the Archive

Taken together, these letters are a rich primary source for social historians and family researchers. They capture language, etiquette, and attitudes in ways that official documents cannot. Every line is dense with meaning: the rhythms of school and work, the uncertainty of illness, the hopefulness of young adulthood, the persistence of faith, and the practicalities of getting by in a modest household.

Importantly, the letters are also emotionally honest. Grief, pride, love, and humour coexist naturally, without sentimentality but with real feeling. There are few grand declarations, but the everyday intimacy—the hopes for a “Happy Xmas & a Bright New Year,” or the bedtime benediction of “sleep well”—testify to bonds that endure.

Historical Context

Most of these letters date from the decade after World War II—a time of austerity, renewal, and gradual change in British society. The formation of the NHS, expansion of university access, end of rationing, and subtle shifts in social attitudes all form the backdrop. The use of postal orders, the reference to rationing and thrift, and the strong communal spirit are characteristic of this era.

The letters are also artefacts of communication before the age of instant messaging. Writing was not only practical, but a key social ritual, helping maintain bonds across distance and hardship. The effort put into writing, the style, and even the paper and ink are part of the story.

Conclusion

The family and friendship letters you have preserved and transcribed are a testament to the ways ordinary people maintained connection, shared burdens, and expressed love in everyday life. They reflect not only their time and place, but also enduring values: resilience, thrift, aspiration, and affection.

In reading and analysing them, we recover not only forgotten voices, but a way of living—measured, caring, and deeply human. Their value lies in their specificity and their universality: each line is personal, yet the themes resonate with families and communities everywhere.

As an archive, these letters are precious—an honest, sometimes unguarded record of life as it was lived. They remind us that history is not only in grand events, but in daily acts of care, written in ink and memory.