Edwardian Malta in Panoramic View: The Cassar Photographs and Society in Transition (1890–1914)

Malta early 20th century views are beautifully preserved in this rare collection of Edwardian panoramic photographs, captured by the Maltese photographer Cassar. Acquired by me in October 2012, these wide-view images offer a vivid glimpse into Malta’s landscapes, harbours, and social life during the early 1900s, perfectly reflecting the atmosphere of the period.

Names and Key Details Extracted

Photographer:

-

Cassar (almost certainly a member of the well-known Cassar family, who were active in Malta as photographers from the late 19th century onwards)

Locations and Captions:

-

Marsamussetto Harbour (correct: Marsamxett Harbour)

-

King Edward VII Avenue, Floriana

-

Uncaptioned wide-view (requires visual study, likely urban Valletta or Sliema area)

-

Grand Harbour, showing Valletta

-

Upper Barracca (Upper Barracca Gardens, Valletta)

Period:

-

Late Victorian to Edwardian (ca. 1890s–1910s)

-

Early 20th century, pre-WWI Malta under British colonial rule.

Expanded Commentary and Historical Context

The Cassar Photographic Legacy

The name Cassar appears frequently in the annals of Maltese photography, particularly during the Edwardian and interwar periods. Families such as the Cassars and Zammit had photographic studios in Valletta, Floriana, and Sliema, recording both grand events and everyday street life. It’s plausible these wide-view images were created for sale as souvenirs or for official use, given their panoramic scale and technical excellence.

1. Marsamxett Harbour

A natural inlet north of Valletta, Marsamxett was less militarised than Grand Harbour and developed as a more civilian, mercantile port. In the early 20th century, it would have seen an eclectic mix of small Maltese luzzu boats, British naval launches, Mediterranean steamers, and leisure craft. The skyline is dominated by the domes and steeples of Valletta and Manoel Island.

Possible people in the scene:

-

Dockworkers, Maltese fishermen, British sailors in white tropical uniforms, vendors, and children playing near the shore.

-

Wealthier families promenading along the water’s edge, including colonial officials and visiting tourists, who were beginning to discover Malta’s mild winters.

Atmosphere:

-

A place of bustling, everyday commerce but also British imperial ceremony. If Cassar captured the morning or late afternoon, the lighting would throw the honey-coloured Maltese limestone into sharp relief, illuminating domed churches and tight, baroque streets.

2. King Edward VII Avenue, Floriana

Floriana was developed as a suburb of Valletta in the 17th–18th centuries, later laid out with broad boulevards in the British era. King Edward VII Avenue—named after the monarch who reigned 1901–1910—was the main ceremonial approach into the city.

Possible details:

-

Military parades: The wide avenue, lined with palms and stone balustrades, was frequently used for imperial processions—red-jacketed British regiments, Maltese Scouts, local dignitaries, and brass bands.

-

Early motorcars and horse-drawn carriages mingling with pedestrians and soldiers on foot.

-

Maltese ladies in traditional għonnella (the iconic black hooded cloak), mingling with Edwardian ladies in high collars and straw hats.

-

Newspaper boys, priests in long black cassocks, and porters wheeling luggage from the main railway terminus just nearby.

3. (Uncaptioned Image)

While uncaptioned, a panoramic photograph in this series likely captures the densely-packed stone buildings of Valletta, Sliema’s developing waterfront, or one of the urban gardens. The Edwardian period saw rapid expansion and urban improvement projects.

Possible focus:

-

Construction workers and builders, as the Sliema and Gżira districts underwent a property boom.

-

Merchants setting up shop, café terraces, young clerks cycling to work, and colonial officials on their way to the Auberge de Castille (government seat).

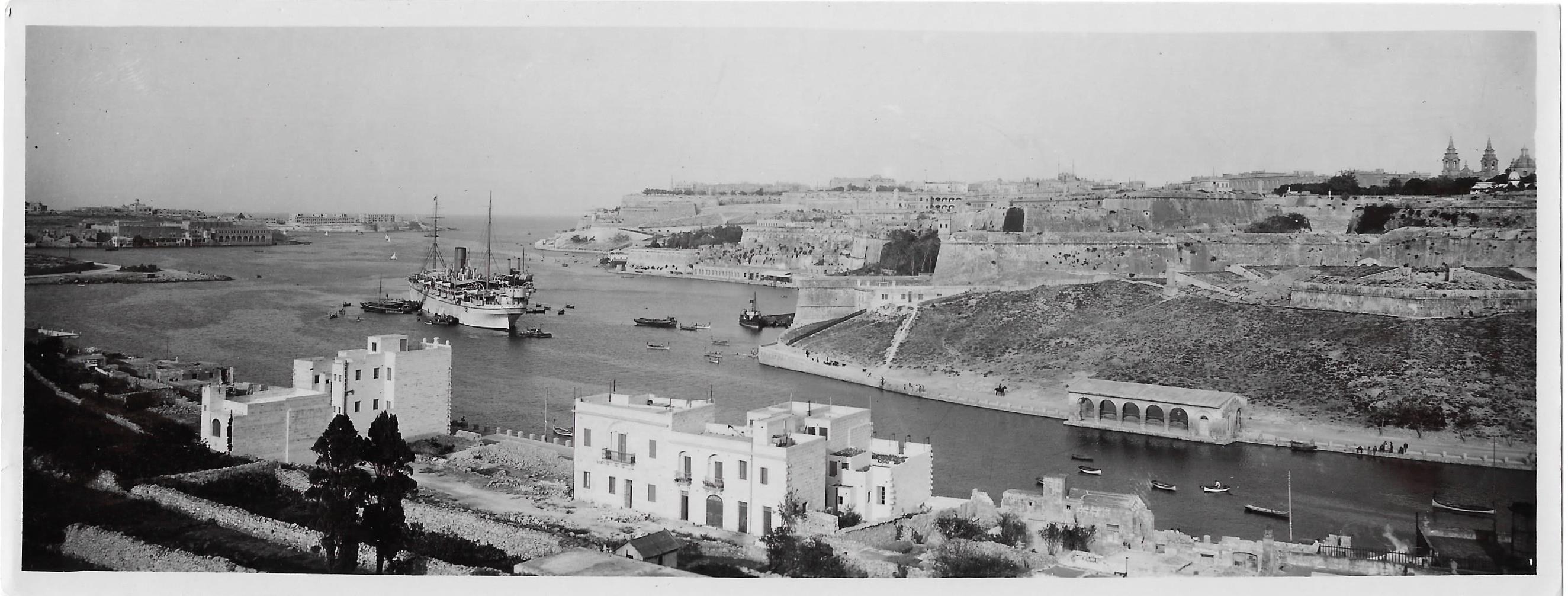

4. Grand Harbour Showing Valletta

Grand Harbour is Malta’s historical lifeline, a spectacular deep-water port encircled by the fortifications of Valletta, the Three Cities (Senglea, Vittoriosa, Cospicua), and the fortified headlands. In the Edwardian period, this was the greatest naval station in the Mediterranean.

Scene specifics:

-

Royal Navy dreadnoughts and coal-powered cruisers, docked alongside steam ferries and Maltese dgħajsa boats ferrying sailors to shore.

-

The bustle of dockyards: Maltese stevedores, British shipwrights, and a cosmopolitan mix of Greeks, Sicilians, and North Africans who worked in the port.

-

Overhead, the skyline is a jagged silhouette of spires, domes, and the massive ramparts built by the Knights of St. John.

-

The “giant steps” of the Baracca, where locals and colonial officials gathered to view the spectacle below.

5. Upper Barracca Gardens

The Upper Barracca (Barrakka ta’ Fuq) is a formal garden atop Valletta’s bastions, with commanding views of Grand Harbour.

Who might appear in the photograph?

-

Edwardian tourists and naval officers posing for photographs, young Maltese couples strolling, children running between the arcades.

-

British army bands playing on Sundays; expatriate families enjoying afternoon tea.

-

In the background, artillery salutes marking royal birthdays or imperial anniversaries.

Edwardian Malta: People, Society, and the British Connection

Names & Types of Individuals (Composite, Based on Era)

-

Sir Leslie Rundle (Governor of Malta, 1909–1915)

-

Sir Paul Boffa (Maltese political leader, early 20th century)

-

Canon Luigi Vella (prominent Valletta priest)

-

Photographers: Joseph Cassar, Emmanuel Cassar (possible members of the Cassar family)

-

Everyday people:

-

Mary Azzopardi: shopkeeper’s daughter, assisting her mother in a Strada Reale bakery

-

George Fenech: British Navy rating on HMS Hibernia, writing a postcard home

-

Salvatore Galea: harbour pilot, guiding liners through Grand Harbour

-

Helen Attard: teacher at the Lyceum, Valletta

-

Social and Political Context

-

British Malta was a key imperial base, and the presence of British regiments, administrators, and their families had a visible effect on fashion, language (widespread use of English), and public ritual.

-

Maltese society was experiencing a shift: growing urban middle class, more access to education, tension between Maltese identity and British colonial culture.

-

Street life: Horse trams, public markets, band clubs, street hawkers, street altars, and religious processions—Maltese Catholicism remained a powerful force.

-

Social division: The elite lived in Valletta or new Sliema apartments; working-class families crowded the backstreets, yet public spaces like the Barracca provided rare intermixing.

Visual and Material Culture

-

Photographic postcards: Images like these were sold to British servicemen and tourists as souvenirs—one of the earliest forms of mass visual culture in Malta.

-

Architecture: British colonial influence is visible in the street names, grand avenues, and public buildings such as the Royal Opera House and the Auberge de Castille.

The Cassar Views: Their Significance

These wide-angle photographs are more than just landscapes; they are portals to a vanished era when Malta balanced its insular traditions with its central role in empire. The Cassar images document not only cityscapes but the energy, optimism, and complexity of Maltese life on the eve of modernity.

-

Marsamxett and Grand Harbour: Epicentres of global trade and imperial power, yet also everyday working harbours filled with ordinary people.

-

King Edward VII Avenue & Upper Barracca: Social theatres, where Maltese and British, rich and poor, met under the Mediterranean sun.

-

Edwardian Malta: A place of transition—between village and city, tradition and empire, old ways and the coming storms of the 20th century.

Conclusion

The ‘Cassar’ panoramic photographs of Malta are a vital historical record. They capture the layered realities of late Victorian and Edwardian Malta—where the Knights’ old stones, British flags, and the rhythms of Maltese daily life all intersect. Each image is inhabited (whether seen or implied) by a cast of characters: dockworkers, shopkeepers, priests, schoolchildren, sailors, colonial families, and, always, the ever-watchful eye of the camera itself.

These are not just city views, but snapshots of a society in transformation—a society shaped by empire, faith, sea, and the slow pulse of Mediterranean time.

Social Crossroads and Civilian Life in Edwardian Malta

Marsamxett in the Edwardian Era

By the turn of the 20th century, Marsamxett had become the favoured anchorage for smaller vessels, pleasure yachts, and the earliest steam ferries shuttling residents and visitors between Valletta and Sliema. While Grand Harbour thundered with the movement of Royal Navy dreadnoughts and coal-fired merchantmen, Marsamxett was animated by the quieter rhythms of civilian life:

-

Local fishermen launched out before dawn, their painted boats a moving thread in the daily tapestry.

-

British naval officers on shore leave sometimes preferred Marsamxett’s less formal atmosphere, using small tenders to reach Manoel Island’s yacht club or the new promenades of Sliema.

-

Women and children would stroll the waterfront, especially on Sundays, enjoying fresh sea breezes and the spectacle of sails and steamers alike.

-

The growing Sliema community—populated increasingly by Maltese middle-class families and expatriate Britons—built elegant terraced houses overlooking the bay, a sign of social aspiration and changing times.

Commerce and Change

Marsamxett was not just a scenic bay but also a space of economic activity and innovation. Small wharves were busy with merchants unloading imported goods—grain, building timber, and British manufactured goods—destined for the urban markets. Manoel Island, once a quarantine station, had by the Edwardian era become a hub for minor ship repairs and occasional naval exercises, further animating the harbour.

The first steam-powered ferries began regular crossings between Sliema and Valletta around this time, symbolising both Malta’s modernisation and its ongoing relationship with the British Empire. Public life along Marsamxett mirrored broader social changes: the expansion of education, a rising Maltese professional class, and increased public rituals such as regattas and holiday parades.

A Social Crossroads

What distinguishes Marsamxett in this era is its status as a social crossroads. Here, one might observe:

-

Maltese priests and nuns on quiet walks, reflecting the enduring influence of the Catholic Church.

-

Young clerks and teachers commuting across the water, the skyline behind them bristling with hope and ambition.

-

Colonial officials and tourists, camera in hand, pausing to record the same views that now reach us through Cassar’s lens.

-

Children playing along the shore, the sounds of laughter mixing with the calls of gulls and the slap of water against stone.

This confluence of people and purposes gave Marsamxett a distinct identity—neither entirely native nor wholly colonial, but something uniquely Maltese in its adaptability and spirit.

Legacy and Significance

Today, the panorama of Marsamxett Harbour captured in “Malta Early 20th Century Views” stands as more than a picturesque scene. It is a portal into a Malta on the cusp of modernity, balancing old rhythms and new energies. The image is a witness to the everyday lives that shaped the island, the gradual transformation of its towns and waterfronts, and the subtle interplay between empire and island, tradition and change.

In the end, Marsamxett’s story is the story of Malta itself—resourceful, resilient, and always looking to the horizon.

King Edward VII Avenue, Floriana: Malta’s Grand Processional Way in the Edwardian Era

Introduction

Among the most striking scenes in the “Malta Early 20th Century Views” collection is the panoramic photograph of King Edward VII Avenue, Floriana. Captured during the height of the Edwardian era by Cassar, this grand boulevard stood as Malta’s ceremonial artery, a stage for public life, imperial ritual, and social aspiration. The image freezes a moment when Floriana’s avenue was not only a literal approach to Valletta—the walled city—but also a symbolic entry into Malta’s modern age.

Origins and Layout

Floriana, originally designed as a fortified suburb of Valletta in the 17th century, became increasingly important under British colonial rule. With the accession of King Edward VII in 1901, the principal boulevard was renamed in his honour, reflecting the British monarchy’s central role in Maltese public life.

King Edward VII Avenue, laid out with a sense of scale and order, was lined with palm trees, stone balustrades, and grand civic buildings. Its generous width allowed for processions, parades, and daily traffic, while its location at the base of Valletta’s ramparts made it the natural path for those entering or leaving the capital.

Life on the Avenue

In the early 20th century, King Edward VII Avenue was the heartbeat of official Malta. This was the route taken by:

-

British governors and colonial dignitaries, their carriages or early motorcars accompanied by police outriders and Maltese military bands.

-

Maltese notables—politicians, lawyers, and businessmen—making their way to government offices or elegant social gatherings.

-

Soldiers and sailors from the Royal Navy and Maltese regiments, marching in crisp formation beneath the fluttering Union Jack.

-

Ordinary Maltese families, dressed in their best for Sunday strolls, children skipping alongside, or pausing to watch the spectacle of a visiting royal or a military review.

During feast days and royal celebrations, the avenue would be festooned with banners and bunting. Brass bands played under the palm trees, while crowds gathered along the pavements to watch the procession of floats, clergy, or troops. Women in the distinctive Maltese għonnella mingled with Edwardian ladies in elaborate hats and gloves, while street vendors hawked roasted nuts and ices.

Architecture and Surroundings

On either side of King Edward VII Avenue rose an eclectic mix of British colonial and Maltese baroque architecture:

-

The Pietà Military Hospital and the Floriana police headquarters marked the importance of order and health under the British regime.

-

The Phoenicia Hotel (opened later in 1947, but its site was already notable for gatherings) hints at the growing role of Malta as a destination for visitors and officials.

-

Near the avenue’s crest, the imposing Portes des Bombes—a baroque gateway—stood as both a military relic and a picturesque monument for all who entered the city.

Nearby lay the railway station, linking Valletta with the rest of the island—a further sign of Malta’s embrace of modern infrastructure.

A Social Crossroads

King Edward VII Avenue in the Edwardian period was a place where Malta’s social worlds overlapped:

-

Maltese and British cultures mingled and sometimes clashed, visible in language, fashion, and even the foods sold by street hawkers.

-

Here, a shopkeeper’s son might rub shoulders with a naval officer, a schoolteacher, or a newly arrived tourist.

-

For young Maltese men, the avenue was a place to see and be seen, aspiring to the fashions of London and the manners of Valletta’s gentry.

-

On election days, political rallies and passionate debates echoed along its length, a sign of Malta’s growing civic awareness and agitation for greater autonomy.

The Avenue in Cassar’s Lens

The panoramic photograph by Cassar likely shows the avenue in its full Edwardian glory—sun-drenched, lively, and crowded with figures in period dress. The composition invites the viewer to imagine the sounds of brass bands, the clip-clop of horses, and the swirl of Mediterranean light on limestone.

Cassar’s image is not only an aesthetic triumph; it is an invaluable historical document, preserving a moment when Floriana’s avenue embodied Malta’s hopes, traditions, and its connection to empire.

Legacy

Today, King Edward VII Avenue—now called Triq Sant’ Anna (St Anne Street)—remains a vital artery through Floriana, but its Edwardian past lingers in the stones and palms, the faded echoes of parades and public ritual. The avenue stands as a testament to a time when Malta was both proudly Maltese and an outpost of empire—open to the world, yet rooted in its own unique identity.

Sliema: Seaside Suburb and Symbol of Modernity in Early 20th Century Malta

Introduction

Sliema, featured in the “Malta Early 20th Century Views” collection, stands as a striking emblem of Malta’s transformation during the Edwardian era. Once a quiet fishing village on the shores of Marsamxett Harbour, Sliema became, by the early 1900s, a vibrant seaside suburb—synonymous with new prosperity, cosmopolitan lifestyles, and a bridge between Maltese tradition and the British colonial world. Through the lens of Cassar’s panoramic photography, Sliema’s story is vividly brought to life.

From Fishing Village to Elegant Suburb

Throughout the 19th century, Sliema was little more than a cluster of fishermen’s cottages and chapels facing the waters north of Valletta. Its very name, derived from the word “peace,” reflected the tranquil existence of its earliest inhabitants. However, as British rule brought new economic opportunities and improved transport links, Sliema’s fortunes changed dramatically.

By the turn of the 20th century, the district was rapidly expanding. Stone townhouses, many with ornate balconies and colourful wooden shutters, rose along the seafront. British administrators, Maltese professionals, and entrepreneurs flocked to Sliema, drawn by its healthy sea air, elegant promenades, and views across the harbour to Valletta’s golden skyline.

Social Life and New Aspirations

Early 20th century Sliema was a place of aspiration and social mobility. The arrival of the British brought new fashions, manners, and opportunities for education. Sliema’s cafés, tea rooms, and social clubs—like the Union Club and the Sliema Band Club—became centres of polite society, where Maltese and British alike gathered for conversation, music, and entertainment.

-

Promenades and Bathing: Sliema’s long, paved seafront became the island’s favourite place for evening strolls, known locally as “il-passeggiata.” Elegant Edwardian ladies in lace and hats paraded arm-in-arm with friends and suitors, while British officers and Maltese professionals greeted acquaintances under the palm trees. On warm days, families and groups of children flocked to the rocky beaches and lidos, marking the beginnings of Malta’s enduring seaside culture.

-

Commerce and Enterprise: Shops, bakeries, and tailors thrived along the main roads, serving both local families and the growing expatriate community. The first department stores and cinemas appeared, and Sliema quickly gained a reputation as a place where one could find the latest British imports—from bicycles and gramophones to new styles of clothing and tea.

Architecture and the Urban Landscape

Cassar’s panoramic photographs reveal a Sliema in transition—old and new standing side by side. The sweeping views show rows of newly built stone houses and apartment blocks, interspersed with older fishermen’s dwellings and chapels dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Churches such as Stella Maris and the Sacred Heart were built to serve the expanding population, their spires soon defining the town’s silhouette.

Transport innovations also transformed the suburb. Steam-powered ferries carried commuters to Valletta, while the introduction of the Malta Tramways Company’s electric trams connected Sliema to Floriana, Valletta, and beyond, making daily travel swift and reliable.

Everyday Life and Diversity

Sliema in the Edwardian era was a crossroads of language, religion, and nationality. English was widely spoken alongside Maltese and Italian. Protestant chapels stood not far from Catholic churches; British naval families sent their children to local schools, while Maltese children recited lessons in both English and their native tongue.

Markets bustled with vendors selling fresh bread, fruit, and fish. The scent of pastizzi and roasted almonds filled the air. On Sundays, the bells of Stella Maris called the faithful to Mass, while the band club prepared for afternoon concerts that drew crowds from across the island.

Sliema’s Legacy in Cassar’s View

Cassar’s images immortalise a unique moment: Sliema as Malta’s seaside window to the world, both thoroughly local and unmistakably cosmopolitan. The views capture the optimism of the era—a place where families dreamed of progress, young people aspired to new careers, and the boundaries between Maltese tradition and British modernity became both blurred and fertile.

Conclusion

By the outbreak of the First World War, Sliema had become Malta’s model suburb—a living symbol of change, ambition, and the possibilities of a new century. Its story, preserved in “Malta Early 20th Century Views,” reminds us that the history of Malta is not only written in its ancient stones, but also in the everyday lives, dreams, and vistas of places like Sliema.

Grand Harbour and Valletta: Malta’s Living Stage in the Edwardian Era

Introduction

Among the most iconic images in the “Malta Early 20th Century Views” collection is the sweeping panorama of Grand Harbour showing Valletta. Captured by the renowned photographer Cassar during the late Victorian and Edwardian period, this view encompasses more than Malta’s geographical heart—it reveals the drama of its history, the vibrancy of its people, and the crossroads of empire and tradition.

The Setting: A Harbour Like No Other

The Grand Harbour, enfolding the southern flank of Valletta, is one of the world’s great natural ports. Its deep, sheltered waters have shaped Malta’s destiny for millennia. In the early 20th century, the harbour was a hive of activity, overlooked by the massive fortifications of Valletta and the ancient Three Cities—Senglea, Vittoriosa, and Cospicua—each echoing centuries of struggle, faith, and resilience.

Cassar’s panoramic photograph sweeps across this landscape: the honey-gold bastions of Valletta, the bustle of merchant wharves, Royal Navy ships at anchor, and fleets of brightly painted Maltese boats (dgħajsa and luzzu) threading the water like coloured beads.

Valletta: The City Above the Harbour

Perched atop the Sciberras Peninsula, Valletta is at once fortress and city, its baroque skyline a testament to both Maltese ambition and the legacy of the Knights of St John. By the Edwardian era, Valletta was the administrative and cultural heart of Malta—a place where history and modernity intersected daily.

The city’s steep streets, grand auberges, and elegant churches—such as St John’s Co-Cathedral—formed the dramatic backdrop for the scene below. British flags snapped in the harbour breeze, while bells and cannon salutes echoed from ramparts during feast days, royal visits, and naval ceremonies.

Life on the Water: Maritime Pulse of Empire

In the early 20th century, the Grand Harbour was among the busiest in the Mediterranean:

-

The Royal Navy used the harbour as a principal base, its grey warships and white-uniformed sailors a daily sight. Malta was sometimes called the “Nurse of the Mediterranean,” as injured servicemen arrived for treatment at the nearby Bighi Naval Hospital.

-

Merchant ships from Britain, Italy, Egypt, and the Levant traded everything from coal to cotton, grain to exotic spices.

-

Maltese dockworkers and lightermen bustled on the wharves, unloading cargo, repairing ships, and piloting local boats through the crowded harbour.

-

Everyday Maltese—shopkeepers, vendors, fishermen, and children—wove their lives around the tides, crossing by ferry or dgħajsa, sometimes for work, sometimes for worship, always for connection.

Social and Cultural Encounters

The Grand Harbour, with Valletta as its crown, was a true social crossroads:

-

British officials and Maltese nobility mingled at official receptions held at the Auberge de Castille or Upper Barracca Gardens, overlooking the water.

-

Band marches, regattas, and feast days drew crowds from every corner of Malta, uniting different classes and cultures in moments of spectacle and shared pride.

-

Immigrant workers from Sicily, Greece, and North Africa contributed to the harbour’s polyglot atmosphere, bringing their own languages, foods, and customs to Malta’s urban mosaic.

-

Photographers like Cassar found endless inspiration in the ever-changing light, water, and life of the harbour—each shot a small epic of its own.

The View from Above: Cassar’s Legacy

Cassar’s panoramic photograph is more than a scenic record; it is a document of modernity arriving on ancient shores. The contrast between stone fortresses and ironclad ships, between baroque domes and new cranes, tells a story of change and continuity. The photograph invites viewers—then and now—to imagine the sounds, scents, and energies of a living harbour: steam whistles, church bells, shouts in Maltese and English, the salty tang of sea air, and the ever-present hum of commerce and conversation.

Conclusion: Grand Harbour as Malta’s Mirror

Grand Harbour, as seen from Valletta in the early 20th century, is more than a marvel of geography or a relic of war. It is Malta’s mirror—reflecting the ambitions of its people, the complexity of its colonial era, and the pulse of an island always open to the world. In Cassar’s lens, this view becomes not just a picture but a living stage, where history and daily life converge, shaping the Malta we know today.

Upper Barracca Gardens: Malta’s Grand Balcony in the Edwardian Imagination

Introduction

Among the jewels of the “Malta Early 20th Century Views” collection, the panoramic image of the Upper Barracca Gardens offers a captivating vantage over both city and sea. Captured by the photographer Cassar, this Edwardian-era scene embodies Malta’s unique blend of Mediterranean beauty, military heritage, and colonial society. From these high arcades atop Valletta’s ramparts, generations have gazed out over the Grand Harbour, watching history unfold beneath the Maltese sun.

Setting the Scene: Valletta’s Sky-High Sanctuary

Perched on the highest point of Valletta’s massive fortifications, the Upper Barracca Gardens (Il-Barrakka ta’ Fuq) were originally created in the 17th century as a private retreat for the Knights of St John. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the gardens had been transformed into a public space—an oasis of palms, fountains, and stone colonnades accessible to all.

Cassar’s panoramic view from this period reveals much: elegant arcades framing the sky, lush greenery contrasting with limestone bastions, and—stretching to the horizon—the drama of Grand Harbour and the Three Cities.

Social Life and Public Ritual

In Edwardian Malta, the Upper Barracca Gardens were more than a viewpoint; they were a social theatre. On Sundays and feast days, families in their best attire strolled along the shaded paths. British officials and Maltese professionals exchanged greetings, children played hide-and-seek among the statues, and couples found quiet corners for whispered conversation.

-

Band concerts and public celebrations regularly animated the gardens, the sound of brass music drifting across the terraces.

-

Artillery salutes from the Saluting Battery below marked royal birthdays, military anniversaries, and important state visits, echoing over the harbour and into the city.

-

Photography and postcards: The spectacular vistas made the Upper Barracca a favourite subject for Cassar and other early photographers, as well as a must-visit for tourists and naval officers eager to send a “wish you were here” home.

A Meeting Place for Cultures

The Upper Barracca was a rare democratic space in a stratified society. Here, Maltese and British, noble and humble, visitor and resident, mingled as equals beneath the arcades. The mixing of languages—Maltese, English, Italian—was as common as the mingling of scents from citrus blossoms and the sea.

-

Naval officers and colonial administrators could be seen pausing at the parapet, binoculars in hand, studying the comings and goings of warships below.

-

Maltese priests and teachers used the gardens for quiet reflection, while schoolchildren sketched the panorama as part of their lessons in art or geography.

-

Vendors and musicians often gathered at the entrance, adding colour and sound to the steady flow of visitors.

Gardens as Living History

The Edwardian period saw the Upper Barracca Gardens become a symbol of Malta’s evolving identity:

-

From exclusivity to openness: Once reserved for the elite Knights, the gardens became a place for all, reflecting the slow democratisation of Maltese society under British rule.

-

A stage for history: The arcades have witnessed everything from royal processions to spontaneous political rallies, and from solemn wartime farewells to jubilant homecomings.

-

Memory and change: For Maltese families, the gardens were the setting for generations of Sunday outings, courtships, and family photographs, many preserved in private albums and archives.

The View Beyond: Cassar’s Legacy

Cassar’s Edwardian photographs capture more than stone and foliage; they hold the atmosphere of an age. Through his lens, the Upper Barracca becomes both a literal and figurative balcony on the world—a place to survey Malta’s beauty and complexity, to watch ships from every nation arrive and depart, and to sense the island’s place at the crossroads of empire, faith, and everyday life.

Conclusion: Malta’s Balcony of Dreams

In the early 20th century, the Upper Barracca Gardens were not only Valletta’s grand balcony but Malta’s stage for public life, memory, and imagination. Cassar’s images preserve that world—a society in transition, at once proud of its past and expectant for the future, gathered above the ancient harbour to watch the unfolding story of Malta.

Cassar’s Malta – A Tapestry of Early 20th Century Life

The “Malta Early 20th Century Views” collection, captured by the photographer Cassar, is far more than a set of panoramic images. Through these rare and evocative photographs, we glimpse the beating heart of Malta at the turn of the 20th century—a society poised between old and new, tradition and progress, insularity and cosmopolitanism.

Each scene—whether the bustling wharves of Marsamxett Harbour, the ceremonial sweep of King Edward VII Avenue in Floriana, the elegant rise of Sliema as a modern suburb, the iconic sweep of Grand Harbour with Valletta, or the sociable oasis of the Upper Barracca Gardens—offers its own story. Cassar’s lens documents not just landscapes, but the lifeways, aspirations, and transitions of an island in flux.

These views capture the essential Edwardian Malta:

-

A crossroads of empire, where British colonial ritual met deep-rooted Maltese custom;

-

A place where new suburbs rose beside ancient bastions, and horse-drawn carts shared space with electric trams and steam ferries;

-

A society where language, faith, fashion, and class were negotiated daily in the city streets, harbours, gardens, and homes.

The images are peopled with life—dockworkers and sailors, children and shopkeepers, priests, musicians, officials, and everyday families. We see not only Malta’s iconic stone, sun, and sea, but also the human energy that animated its Edwardian era.

The Enduring Value of Cassar’s Photographs

Today, Cassar’s early 20th-century Malta views stand as a unique historical record:

-

For historians and genealogists, they offer invaluable primary evidence of how Malta looked, moved, and lived in a vanished age.

-

For the public and diaspora, they evoke nostalgia, pride, and connection with Malta’s rich heritage.

-

For all viewers, they are a reminder that history is made not just by kings, knights, or governors, but by the daily rituals and shared spaces of ordinary people.

Closing Reflection

As we move further from the Edwardian world, the significance of such images only grows. They remind us that Malta’s story is not only written in archives or official histories, but is also preserved in the visual memory of places, faces, and moments—fragments that together create a tapestry of identity and belonging.

Through Cassar’s eyes, we are offered a balcony onto early 20th-century Malta—a living, changing island at the crossroads of history.

These photographs invite us not only to look, but to see: to recognise the complexity, resilience, and beauty of Malta and its people as they stepped into the modern age.

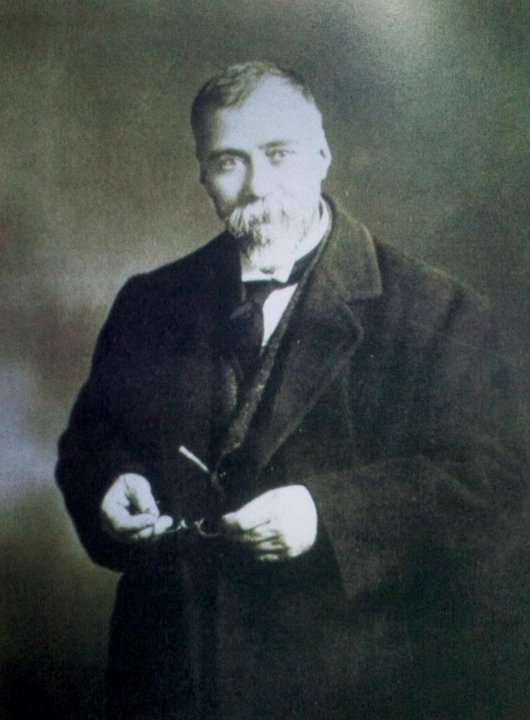

Salvatore Lorenzo Cassar (1855–1928): Malta’s Pioneering Early Photographer

Salvatore Lorenzo Cassar was one of Malta’s most prominent early photographers, active during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1855, Cassar established himself as a skilled portrait and landscape photographer, running a respected studio in Valletta. He became well known for his panoramic images and postcards, documenting the transformation of Malta under British colonial rule.

Cassar’s work captured both urban and rural scenes, including iconic views of Valletta, Grand Harbour, Sliema, and major public events. His photographs are recognised for their technical quality and documentary value, providing a visual record of Maltese society, architecture, and daily life during a period of rapid change.

He was part of a wider Cassar photographic family, with relatives who continued the business into the 20th century. Salvatore Lorenzo Cassar died in 1928, leaving behind a substantial archive of images that remain crucial to Malta’s visual heritage and historical memory.