Stanley Parrish James (1897 – 14 April 1918): A Short Life Remembered

Stanley Parrish James of Wood Green served in the Middlesex Regiment during WW1. He was born in 1897 into a modest, loving family. He was baptised on 26 August 1900 at Camberwell, beginning life in the bustling suburbs of London at the dawn of the twentieth century. By the 1901 Census, Stanley was living in Islington alongside his parents—his mother, Emily (née Say, born 1 August 1866 in Bath), and his father, John James, a railway clerk (born 1 November 1866 in New Southgate). Stanley also had a younger brother, Reginald John James, who was born on 8 June 1902 and would live until 1974.

The James family was typical of the striving lower-middle class of Edwardian London, moving to Wood Green by 1911 as John’s work on the railways offered stability and hope for the future. Their home on Maryland Road became the family’s base during the turbulent years of the First World War.

From Boyhood to War: Enlistment and Service

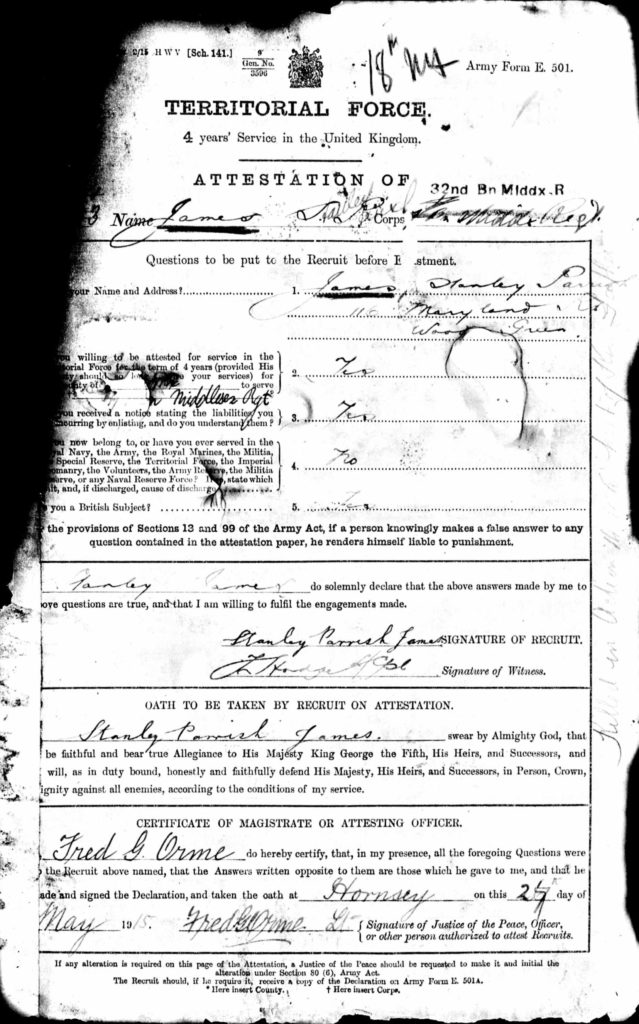

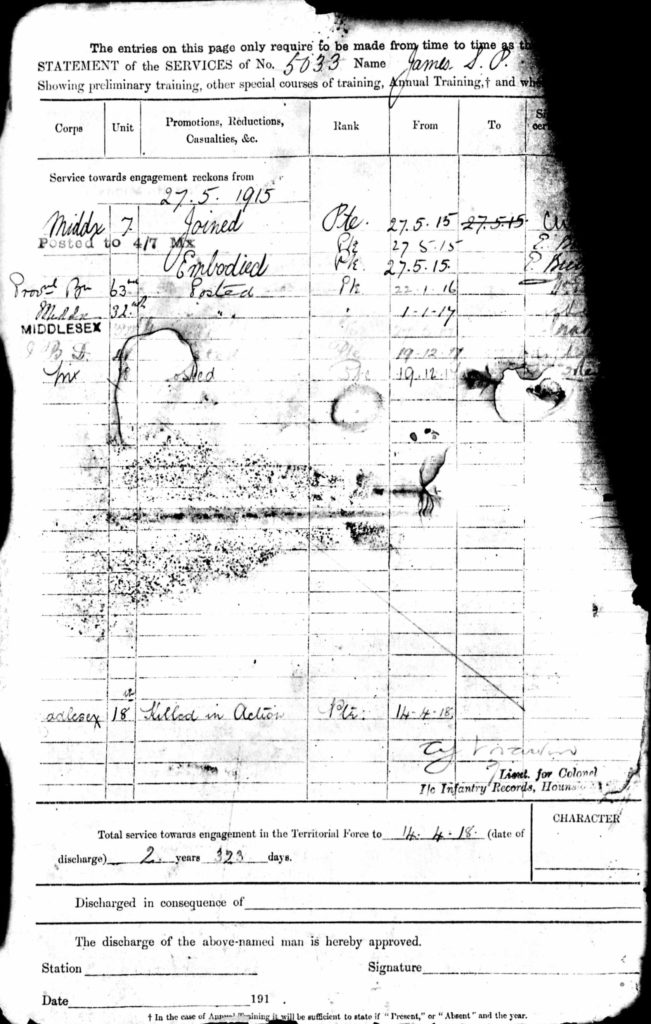

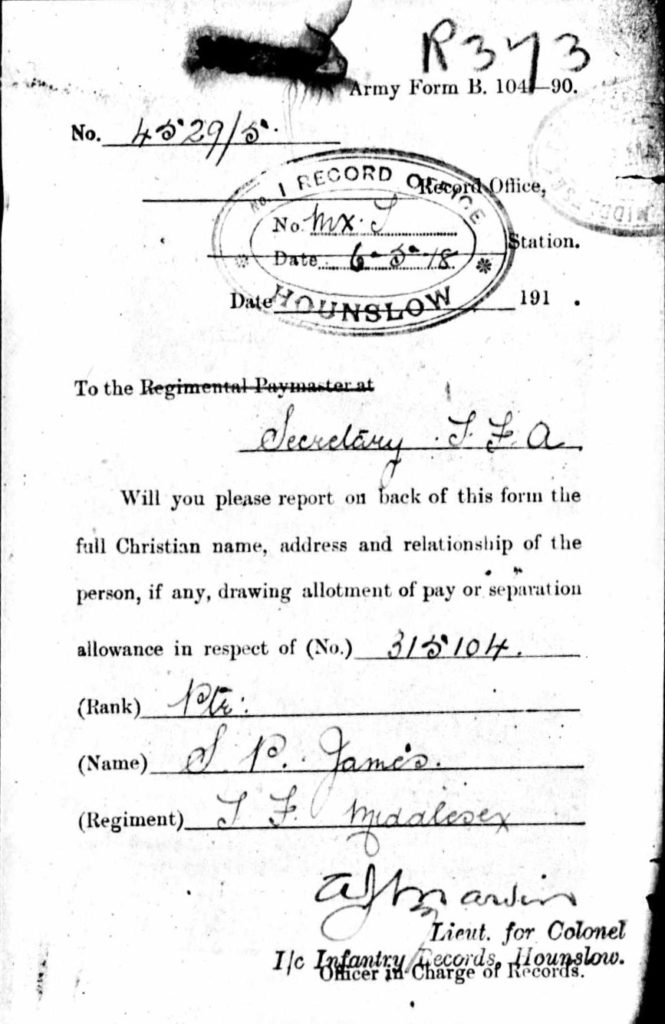

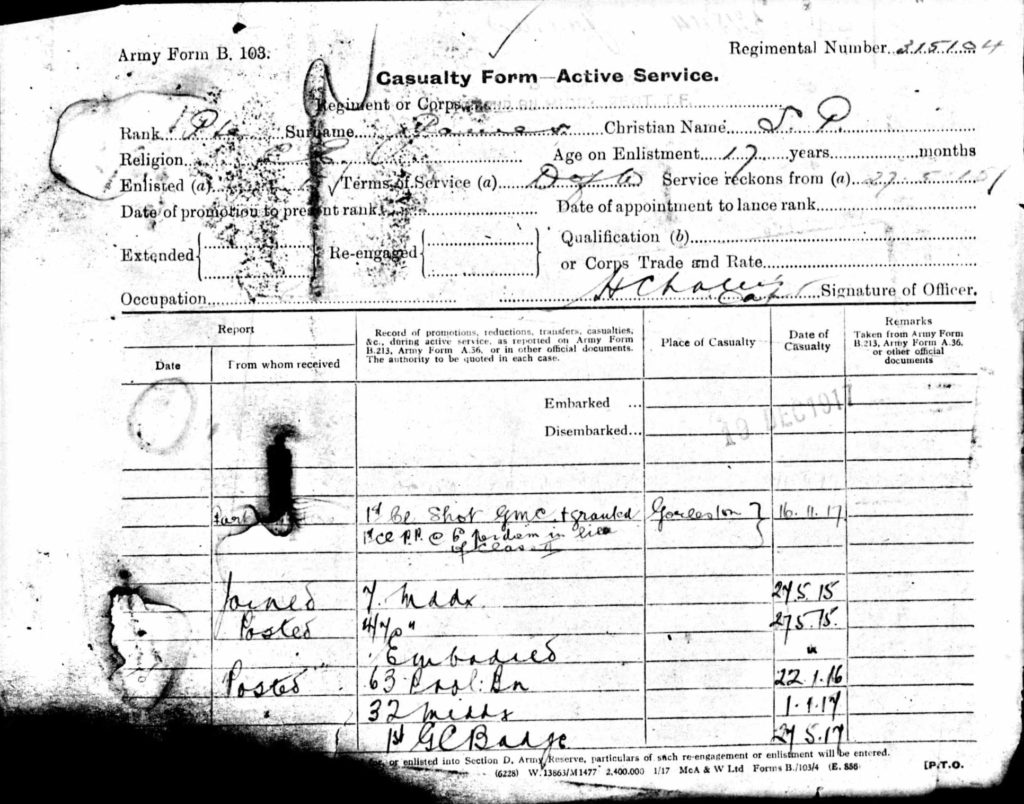

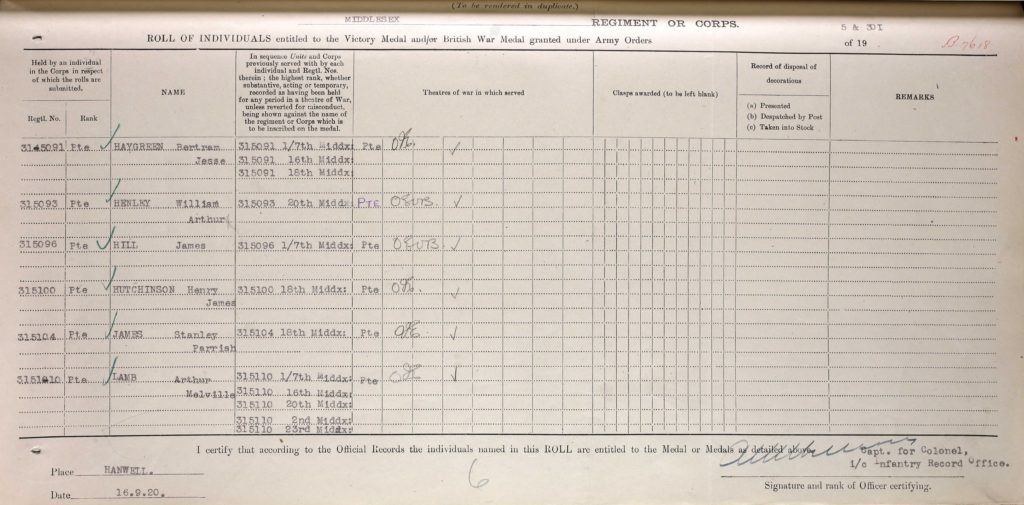

On 27 May 1915, Stanley made the fateful decision to enlist in the army at Hornsey, just seventeen years old and swept up in the fervour and sense of duty that gripped the nation. He joined the 18th Battalion of the Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex) Regiment. Assigned Regimental Number T.F.315104, Stanley joined countless other young men in the muddy training camps and, later, the front lines of the Western Front.

Despite his youth, Stanley would have experienced the full realities of war: the camaraderie and terror of trench life, the constant uncertainty, and the sudden violence of battle. Like many in his generation, he shouldered responsibilities and faced dangers that had no parallel in civilian life.

Final Days and Tragic News

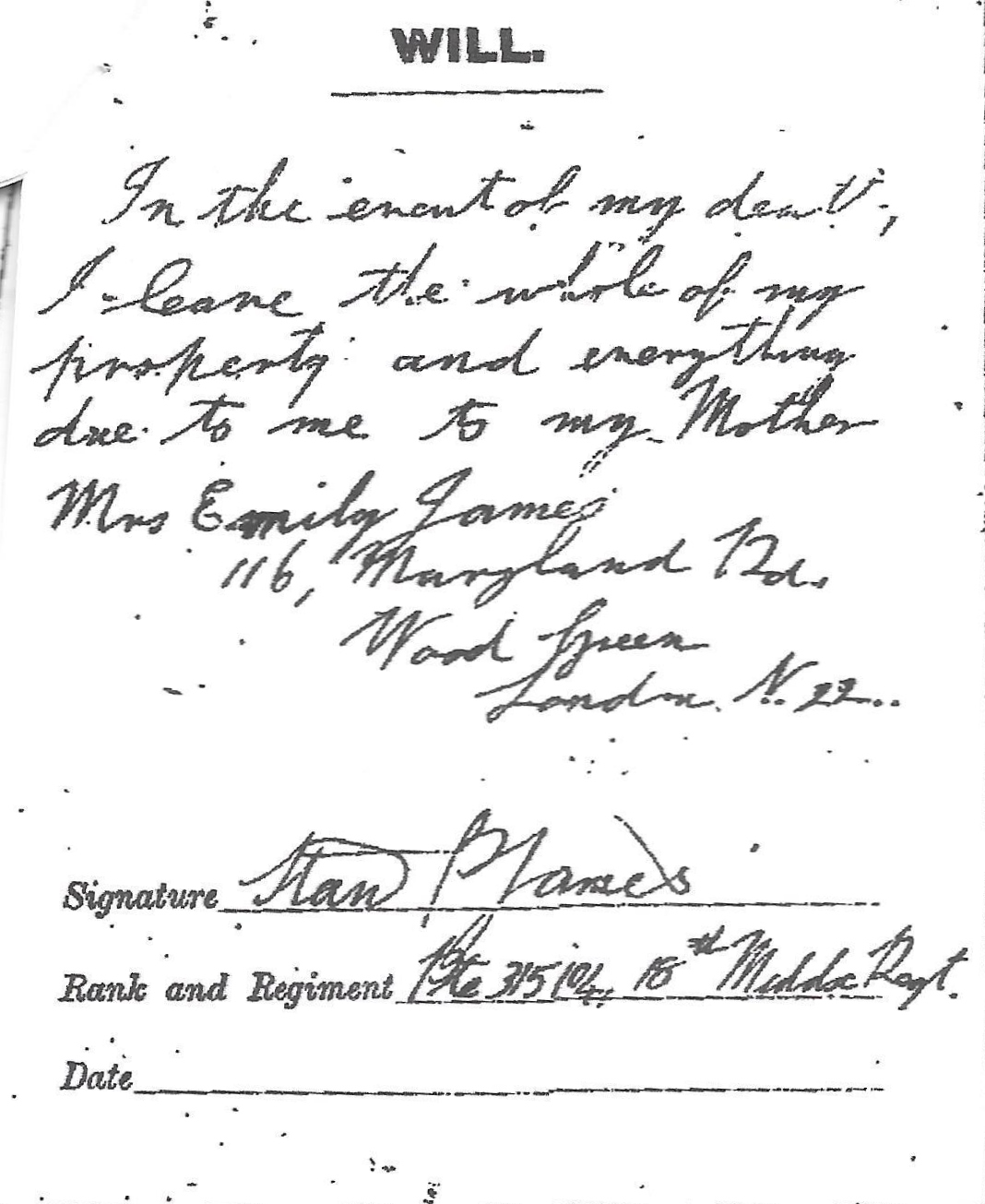

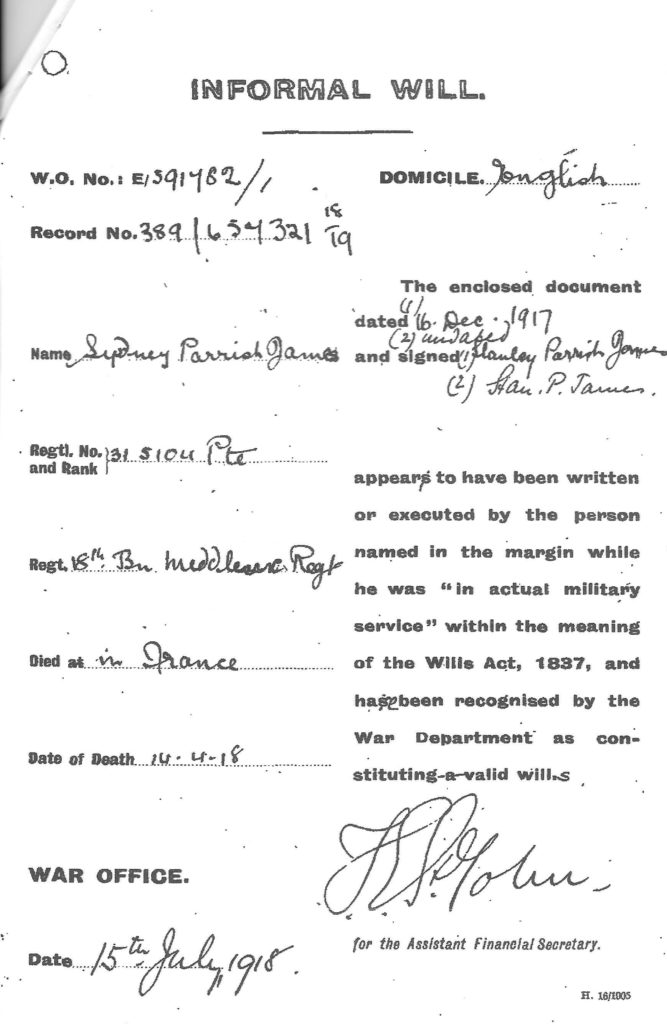

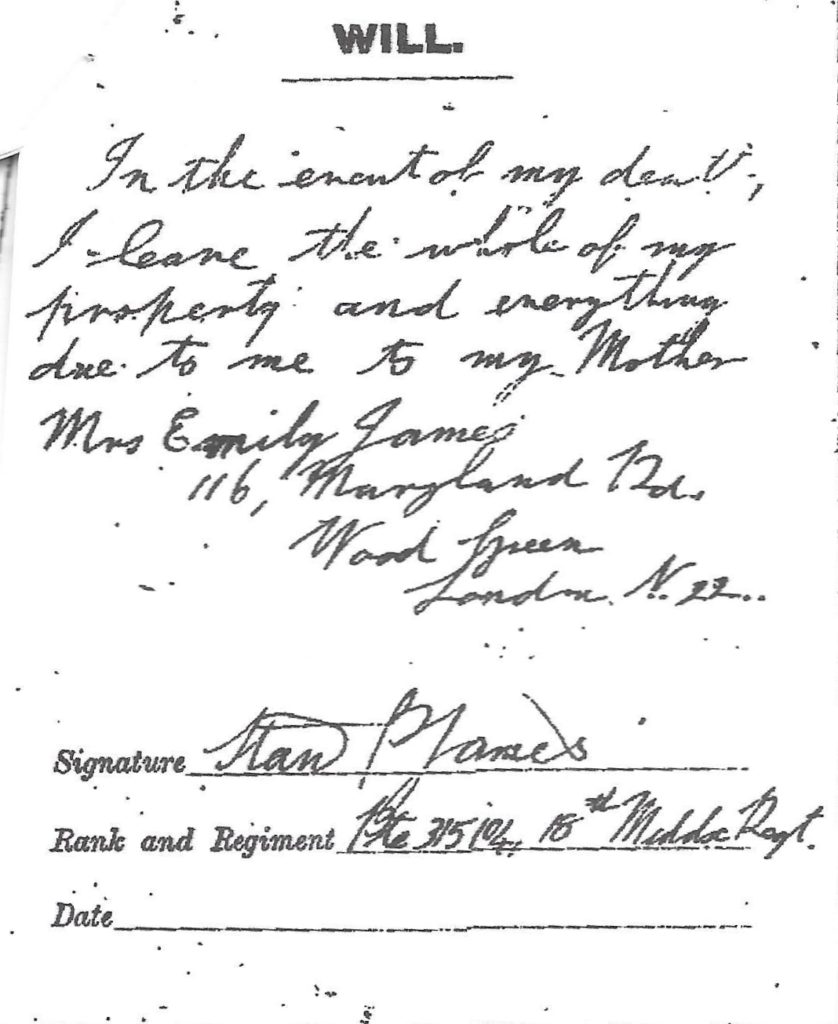

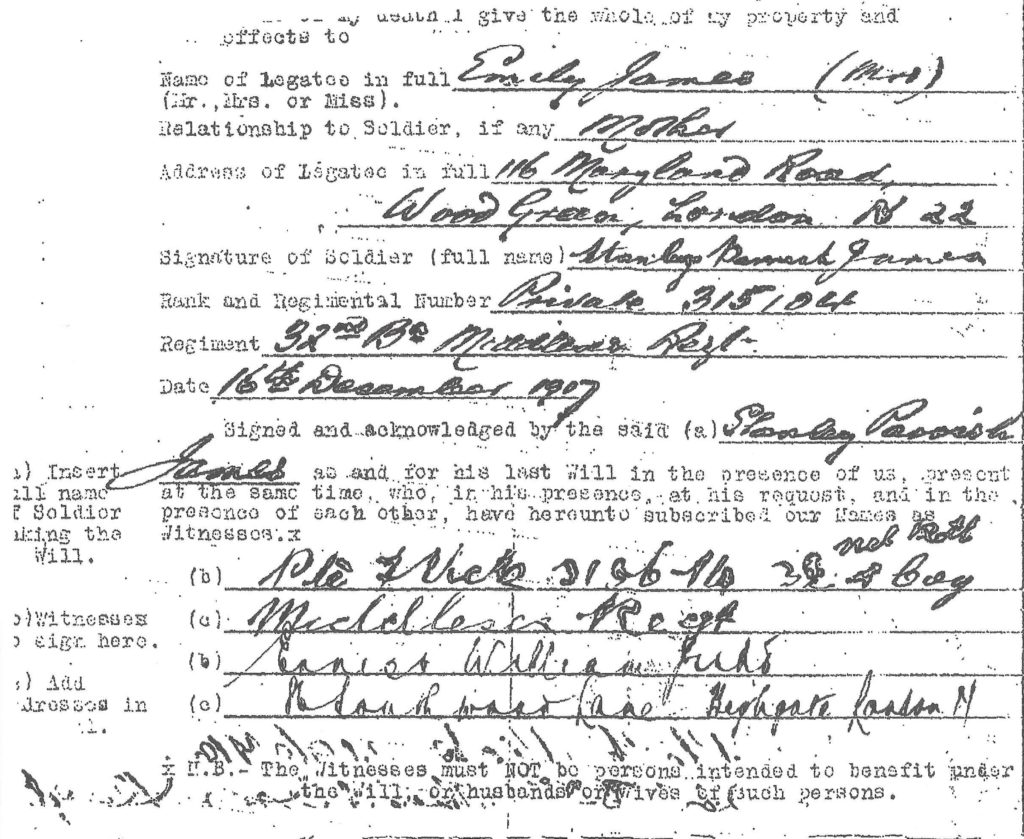

In April 1918, with the war entering its final and most brutal phase, Stanley found himself stationed in Flanders—scene of some of the bloodiest fighting of the conflict. On 14 April 1918, aged just 20 or 21, he was killed in action. The details of his death remain lost to history, but just before he died, Stanley hurriedly wrote his will—almost certainly from his trench, amid the chaos of battle.

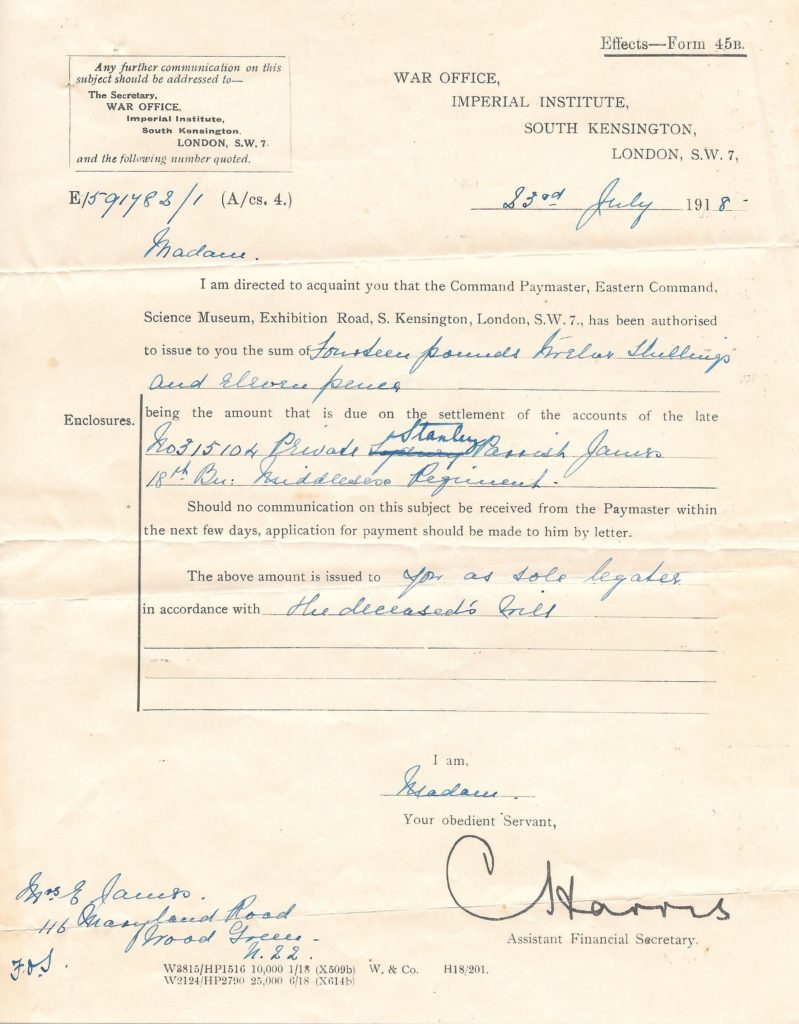

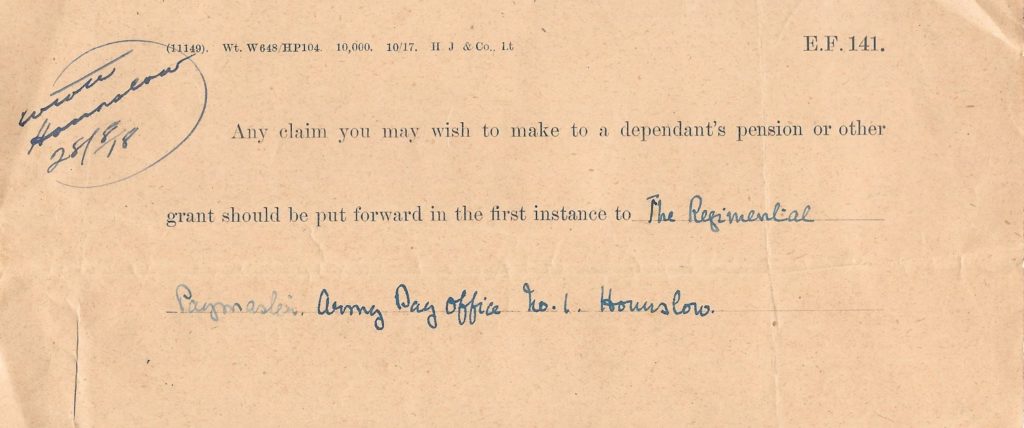

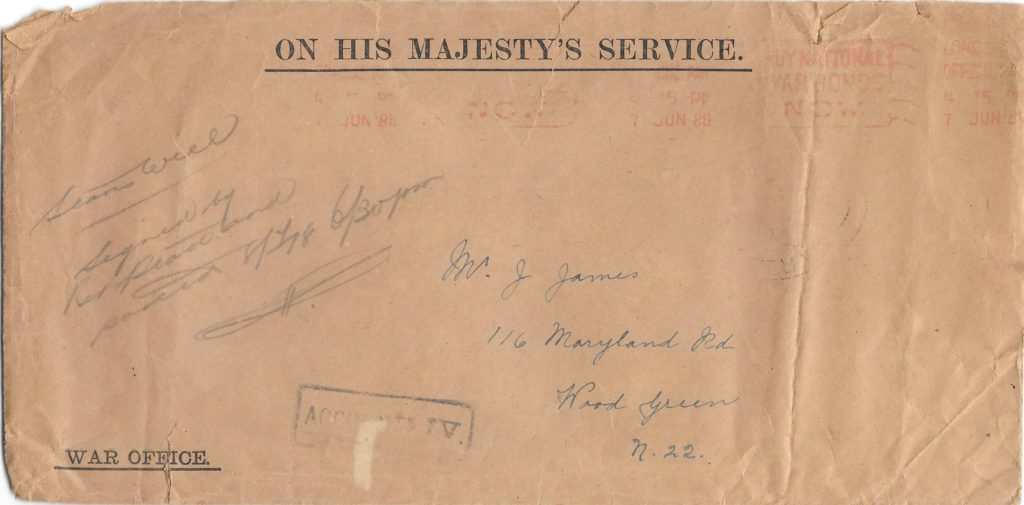

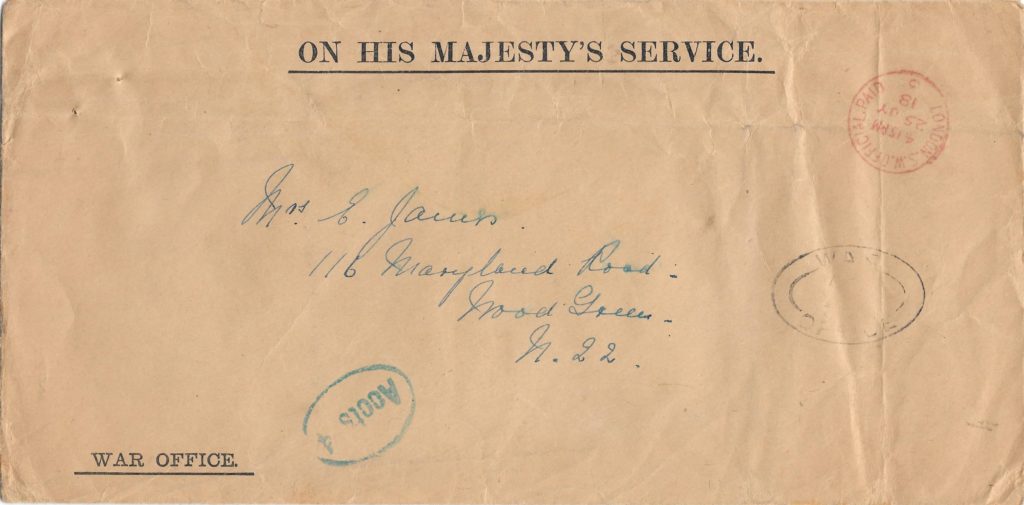

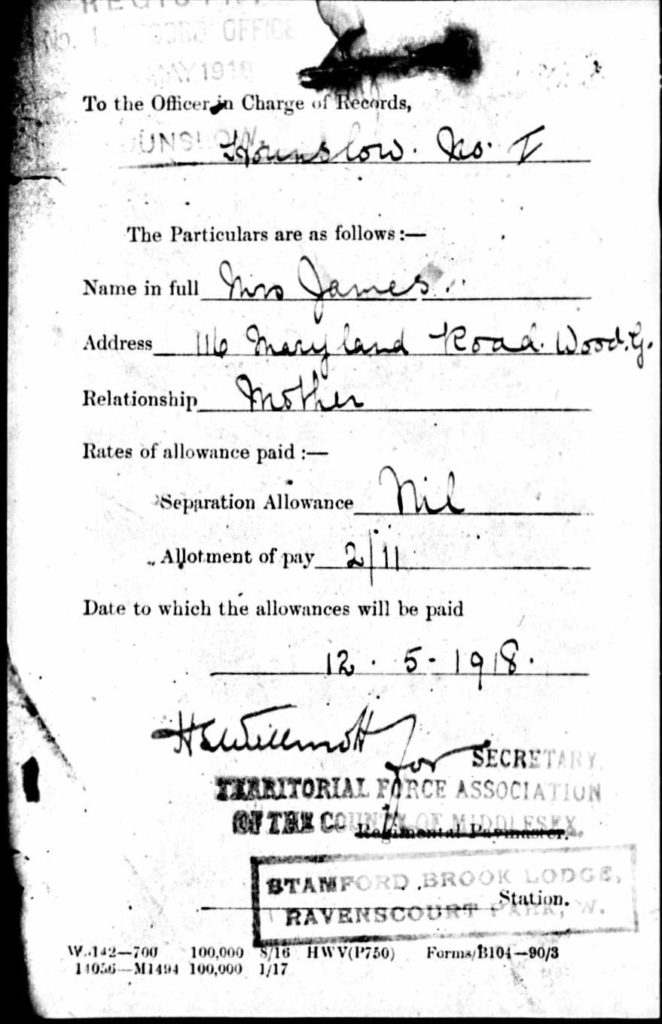

News of Stanley’s death reached his parents and younger brother in Wood Green in the weeks that followed. The process, as with so many wartime notifications, was impersonal and bureaucratic—official letters, telegrams, and a sense of numbing finality. One can only imagine the impact this had on Emily, John, and Reginald: the sense of loss, the emptiness left by a son and brother who had gone to war barely a man and never returned.

Stanley’s short life is a stark reminder of a generation lost to the Great War. Like so many others, his story is one of ordinary promise extinguished far too soon—a fate shared by families up and down Britain, leaving a legacy of quiet grief and enduring memory.

Related Archives:

Wood Green in the Early 20th Century: Community and Change

At the turn of the twentieth century, Wood Green was a rapidly developing suburb in North London. Once a rural outpost on the edge of the city, it was being transformed by the arrival of new railway lines, tramways, and an expanding population. Families like the Jameses—aspiring, working- or lower-middle class—were drawn to the area by affordable housing and the promise of regular employment, especially on the railways or in the growing number of local shops and offices.

Wood Green’s streets in 1914 would have echoed with the sounds of children playing, the rattle of horse-drawn carts, and the new electric trams running along the High Road. There were parks, local markets, a vibrant social life centred around churches, pubs, and friendly societies. During the war, the area was marked by a sense of patriotic duty: recruitment rallies, bandstands flying the Union Jack, and increasing numbers of women taking up roles in local factories and services. Every family knew someone who had gone to war, and as the months passed, news of casualties began to cast a long shadow over the community.

The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment), 18th Battalion

Stanley Parrish James enlisted in the Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex) Regiment, specifically the 18th (Service) Battalion, one of many “Pals Battalions” raised during the First World War. The Middlesex Regiment recruited heavily from North and West London—ordinary clerks, shop assistants, and apprentices joining up together, often from the same streets or workplaces. This created units bound by strong local ties but also meant that, in times of heavy casualties, entire neighbourhoods could be plunged into grief at once.

The 18th Battalion was formed in 1914 and quickly sent for training before embarking to the Western Front, where it was involved in some of the war’s fiercest battles. The men of the Middlesex saw action on the Somme, at Ypres, and in the final German offensives of 1918. Conditions were harsh: cold, mud, shellfire, and the constant threat of attack. Despite this, battalion diaries show a spirit of endurance and camaraderie among the rank and file.

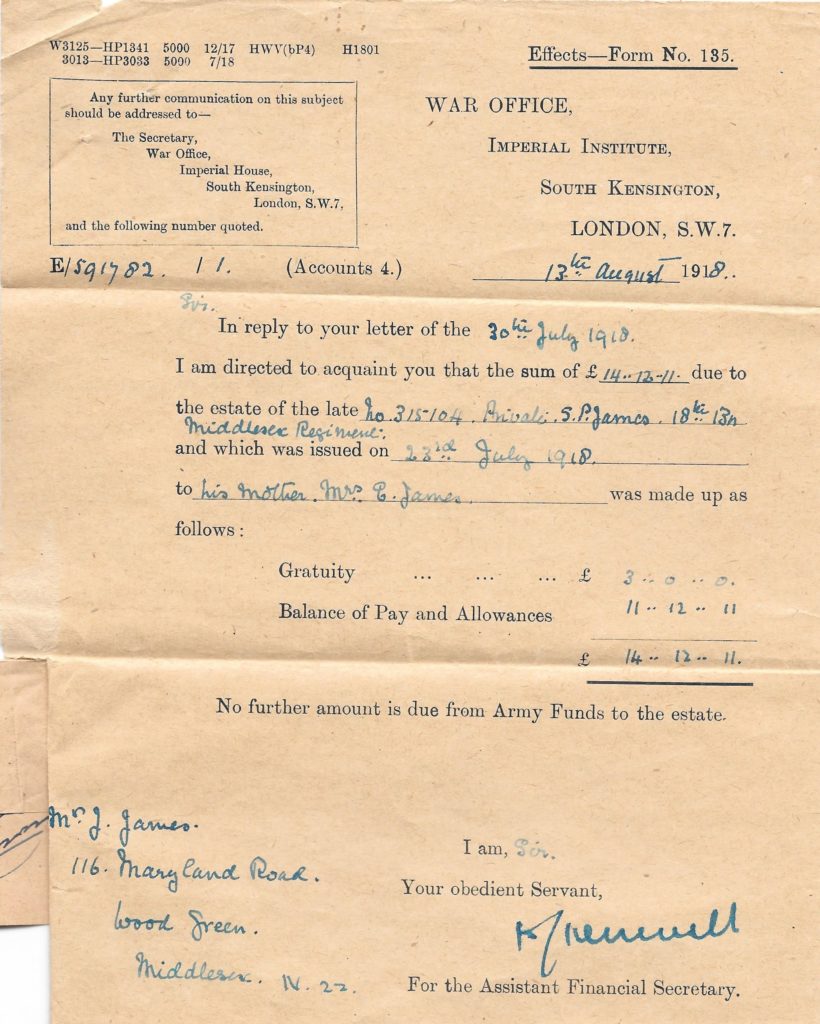

Wartime Notification: Family Grief and the Bureaucracy of Loss

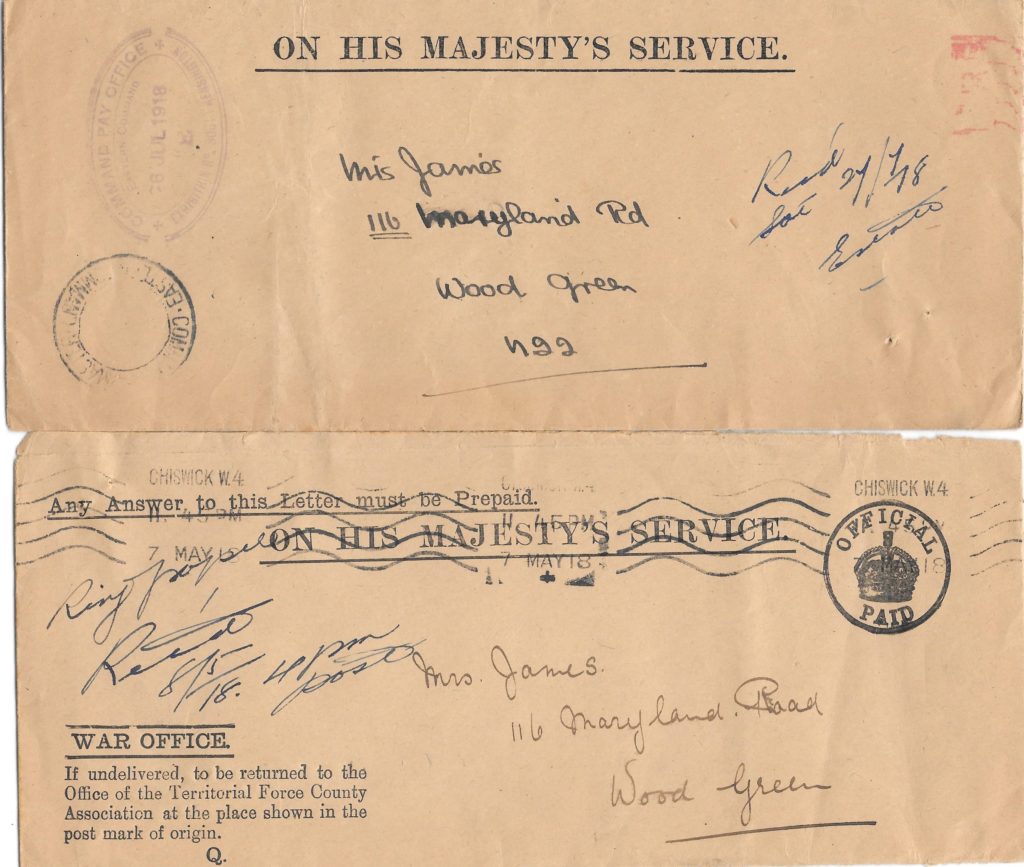

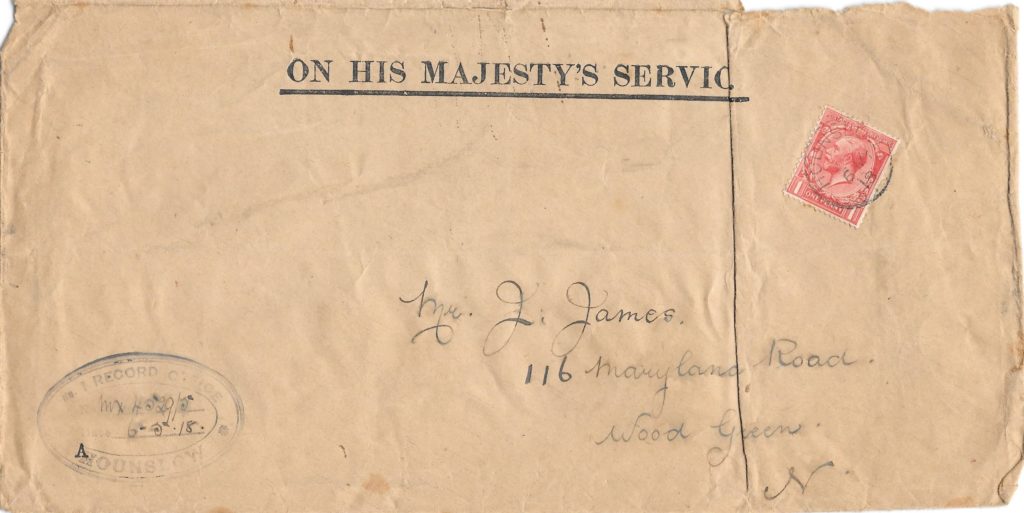

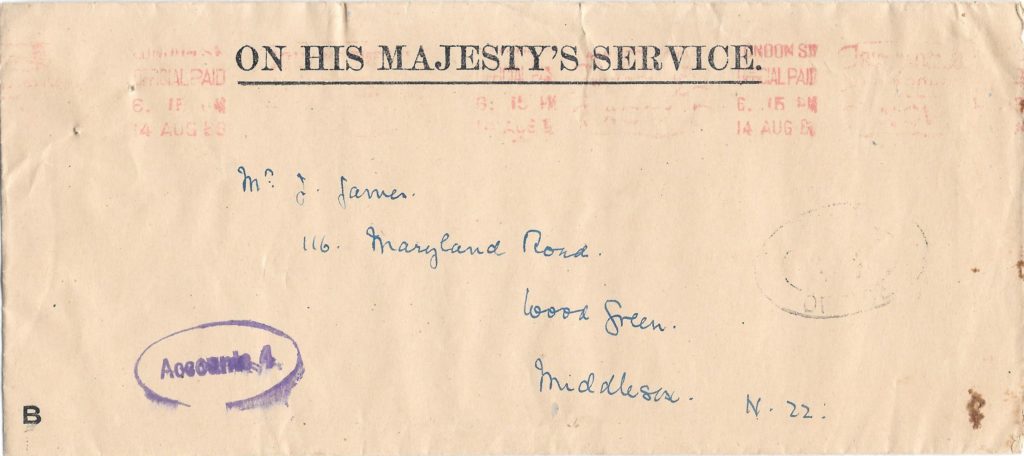

For families like the Jameses, the experience of receiving news from the front was fraught with dread. Communication was slow and uncertain: weeks could pass without word, and rumours often spread faster than facts. When official news of a death did arrive, it came not in person, but by telegram or letter—formal, impersonal, sometimes delivered by a boy from the local post office or a passing railway porter.

The language of these notifications was cold by necessity: “We regret to inform you…” or “It is my painful duty…” The process reflected the sheer scale of loss faced by Britain; individual grief was often subsumed beneath official paperwork, compensation claims, and the return of a soldier’s personal effects—perhaps a wallet, a watch, or the hastily written will that Stanley himself drafted in the trenches.

For Stanley’s parents, Emily and John, and his younger brother Reginald, the impact was immediate and profound. The loss of a son and brother, just as he was coming into adulthood, left an emptiness that could never be filled. Neighbours, church congregations, and co-workers might offer sympathy, but the reality of wartime loss was private and enduring. The James family’s story stands for thousands of similar tragedies in Wood Green and across Britain—a generation shaped, and in many cases shattered, by the Great War.