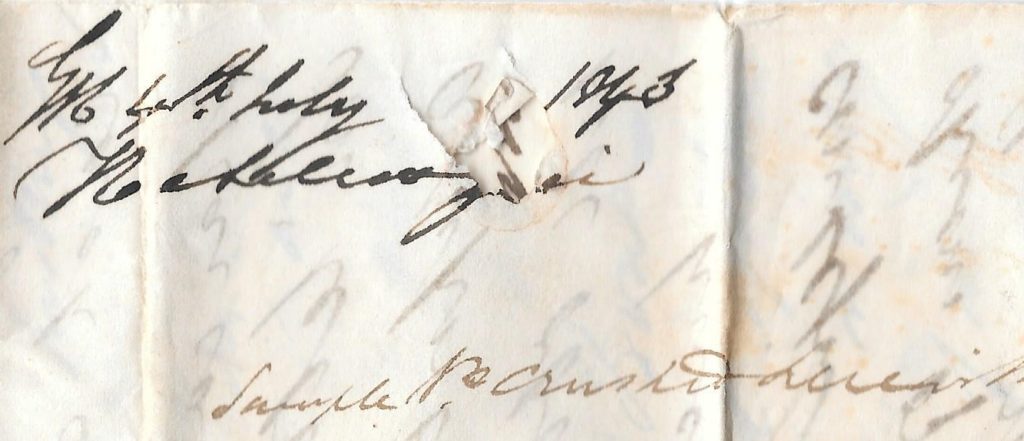

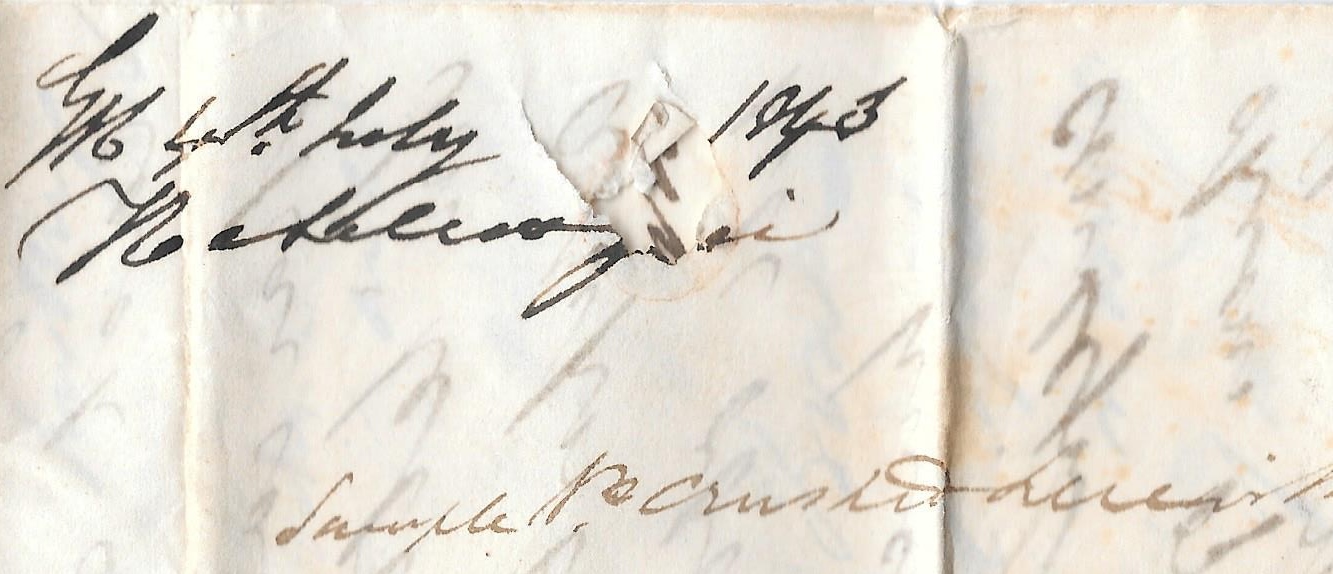

William Macfir letter 4 July 1843

This page presents the full text and analysis of a fascinating letter written by William Macfir to his father John Macfir on 4 July 1843. (Go straight to analysis here)

The letter, sent from Greenock, Scotland, offers a rare glimpse into Victorian family life, travel, and business during the early industrial era. It combines personal updates about family members and their journey with detailed discussions of technical, industrial, and water supply issues, reflecting the everyday realities and challenges faced by a professional Scottish family in the 1840s.

Despite some sections becoming difficult to read, the William Macfir letter 4 July 1843 provides detailed insights into travel arrangements, scientific and industrial testing, water supply challenges, and business instructions. The letter also mentions important figures such as Mr. John Marquis, Charles Cunningham, and R. Rutherford, highlighting the close personal and professional networks of the time.

Although the handwriting fades, this Victorian-era letter, William Macfir letter 4 July 1843, remains a valuable artefact of 1840s communication and Scottish family life.

This page presents the full text and analysis of a remarkable letter written by William Macfir to his father John Macfir on 4 July 1843. The letter, sent from Greenock, Scotland, offers a rare glimpse into Victorian family life, travel, and business during the early industrial era. It combines personal updates about family members and their journey with detailed discussions of technical, industrial, and water supply issues, reflecting the everyday realities and challenges faced by a professional Scottish family in the 1840s.

(Go straight to analysis here)

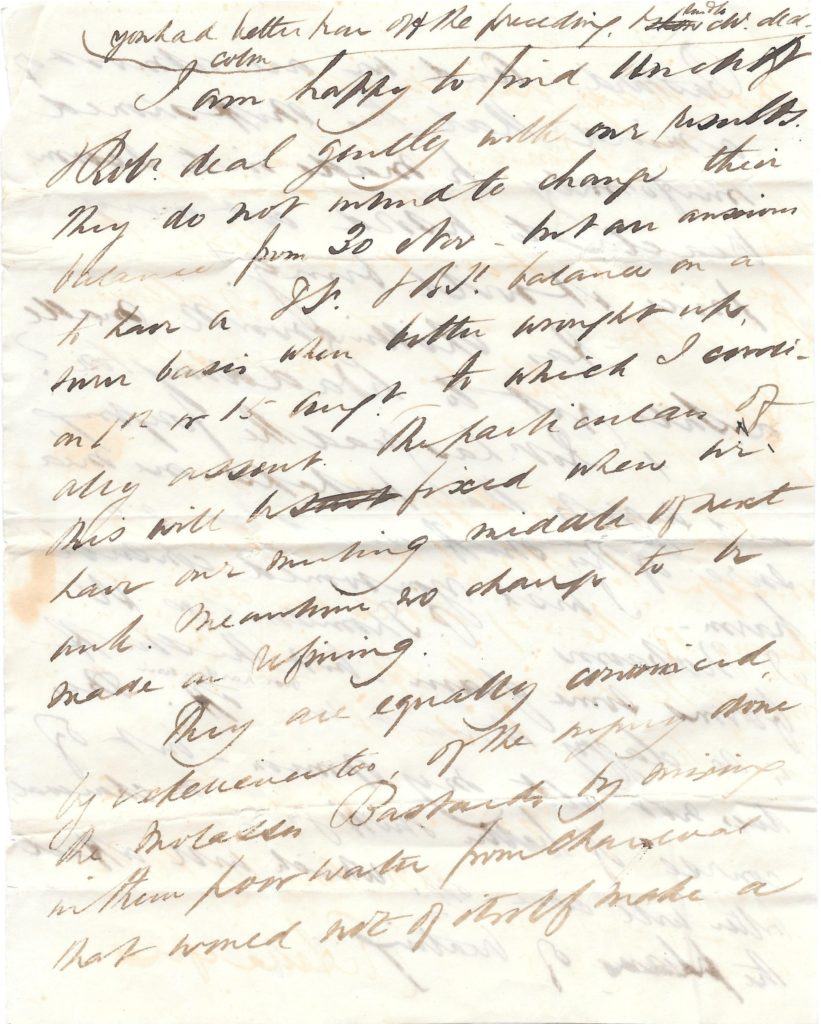

The transcription

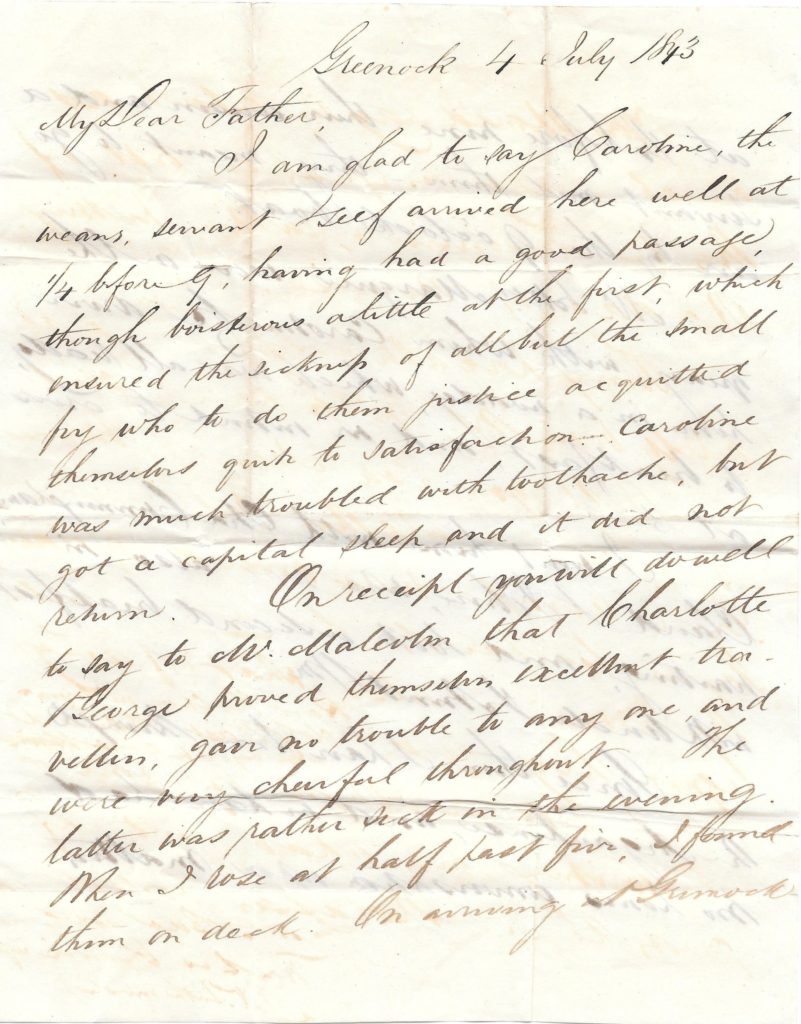

Greenock 4 July 1843

My Dear Father,

I am glad to say Caroline, the maids, servant, & self arrived here well at 4 before 9, having had a good passage, though boisterous a little at the first, which ensured the sickness of all but the small fry, who to do them justice acquitted themselves quite to satisfaction. Caroline was much troubled with toothache, but got a capital sleep and it did not return.

On receipt you will do well to say to Dr. Malcolm that Charlotte & Florrie proved themselves excellent travellers, gave no trouble to anyone and were very cheerful throughout. The latter was rather sick in the evening. When I was at half last five, I found them on deck. On arriving I found…

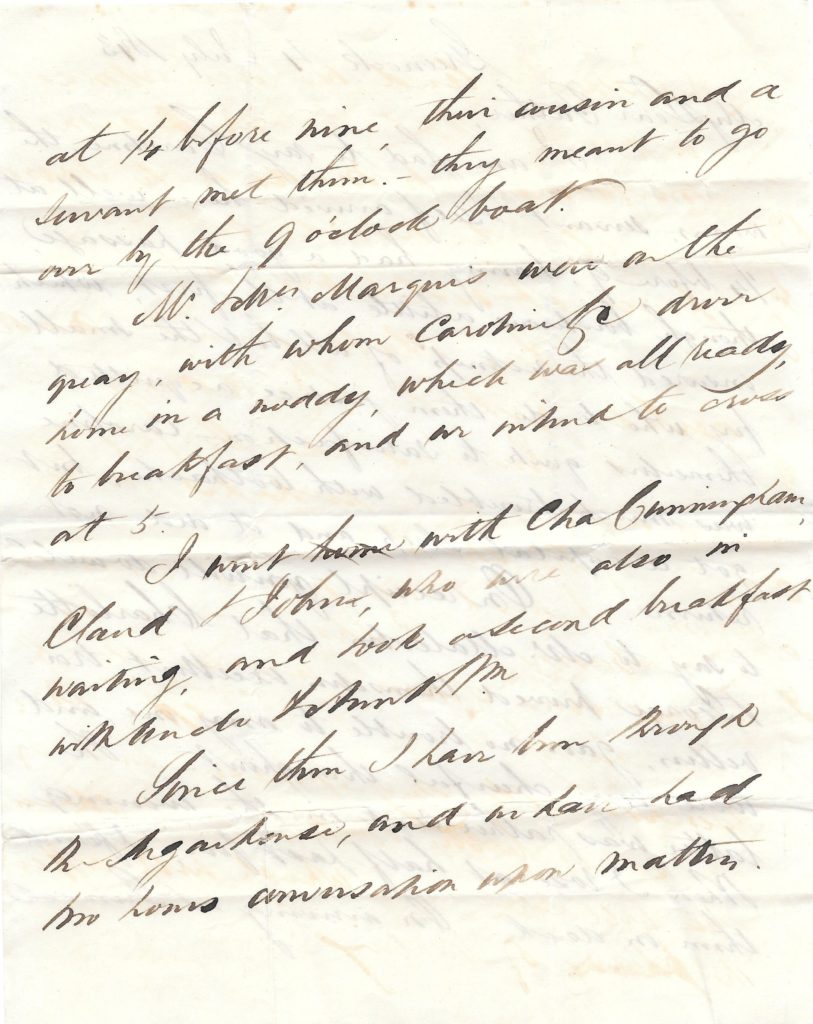

at ½ before nine their cousin and a servant met them. They meant to go over by the 9 o’clock boat.

Mr. John Marquis was on the quay, with whom Caroline & I drove home in a noddy, which was all ready to breakfast, and we intend to dine at 3.

I met home with Cha Cunningham; Claud & John, who were also in waiting, and took a second breakfast with uncle John & Mr.

Since then I have been through the regular lines and in law had two hours conversation upon matters,

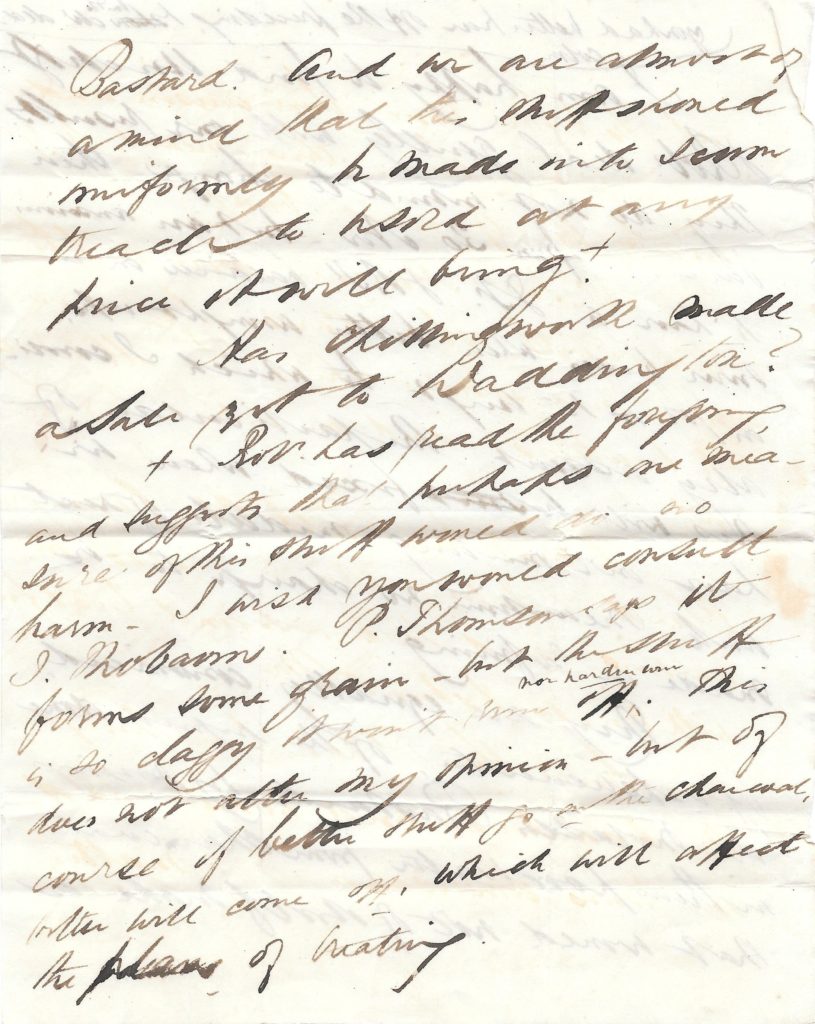

Bastard. And we are almost of a mind that his [shipment? should] uniformly be made with seam tracks, to break at any price it will bring.

Has Atkin quite made a sale yet to Reading? + Roy has read the [prospectus?] and suggests the pulps are true and high, the oil formed in [mass?] of this not named would assist [burning?]. I wish you would consult P. Graham re it.

J. Robinson forms some grain – but the [mass, nor hardness nor texture?] is so clay[ey] in my opinion – but it does not alter my mind as to the channel, course of better stuff for the channel, which will affect the plan of treating.

you had better have Mr. [the preceding letter] & Ch. [Charles?] also.

I am happy to find the old Rats deal gently with our results. They do not intimate change their place from 30 [c/hr?] before invasion. I find a P.S. H.S. balance on a tan, when better wrought up, even basis, to which I could add 12 to 15 [cwt?]. The fair value is only present. The fair value is fixed when water is running, middle of next. This will not bring middle of next [week?]. Meantime so damp to be made as spring.

They are equally convinced of the advisement of the piping done by extension. Bastards, by raising up their low water from drains and not [turned?] out, I shall make a

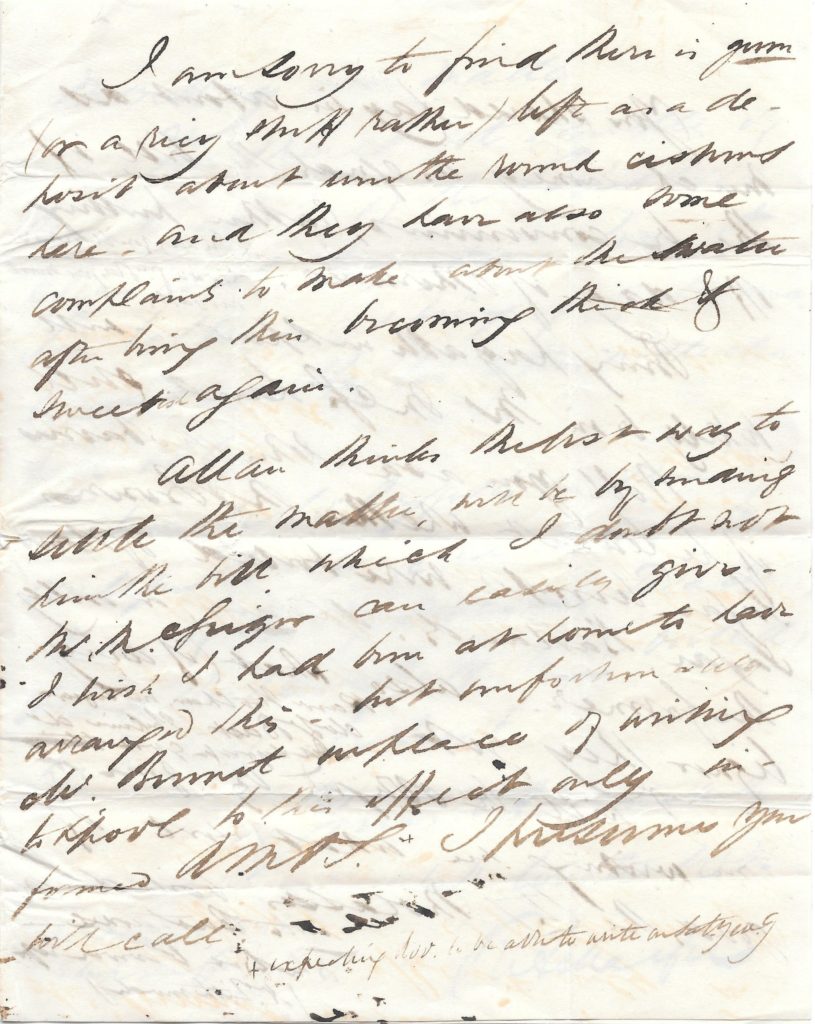

I am sorry to find there is gum of a very mild nature left in a deposit about and the round cisterns here – and they have also more complaints to make about the water after being thus becoming thick & sweet again.

Allan thinks the best way to settle the matter will be by mixing with the hill, which I don’t at all wish to do, which our eating will enjoy. I wish I had him at home to hear and answer his own statements, but unfortunately I must depend on the silence of writing.

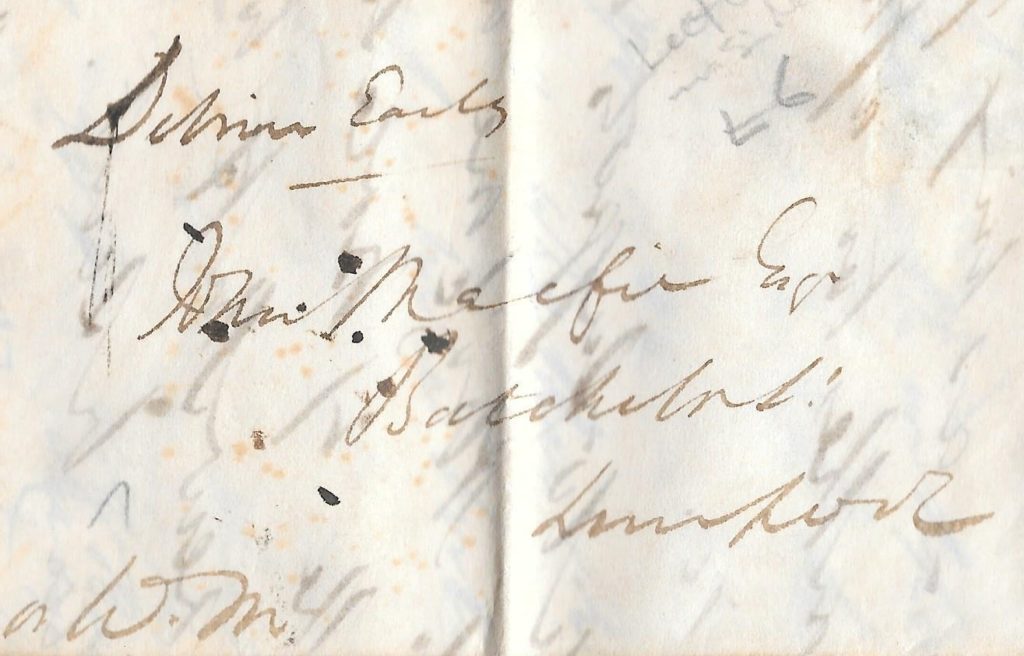

With kindest affection to his mother & all,

Yours, W.M. Macfir

I will call.

[hoping but to be able to write and stay up]

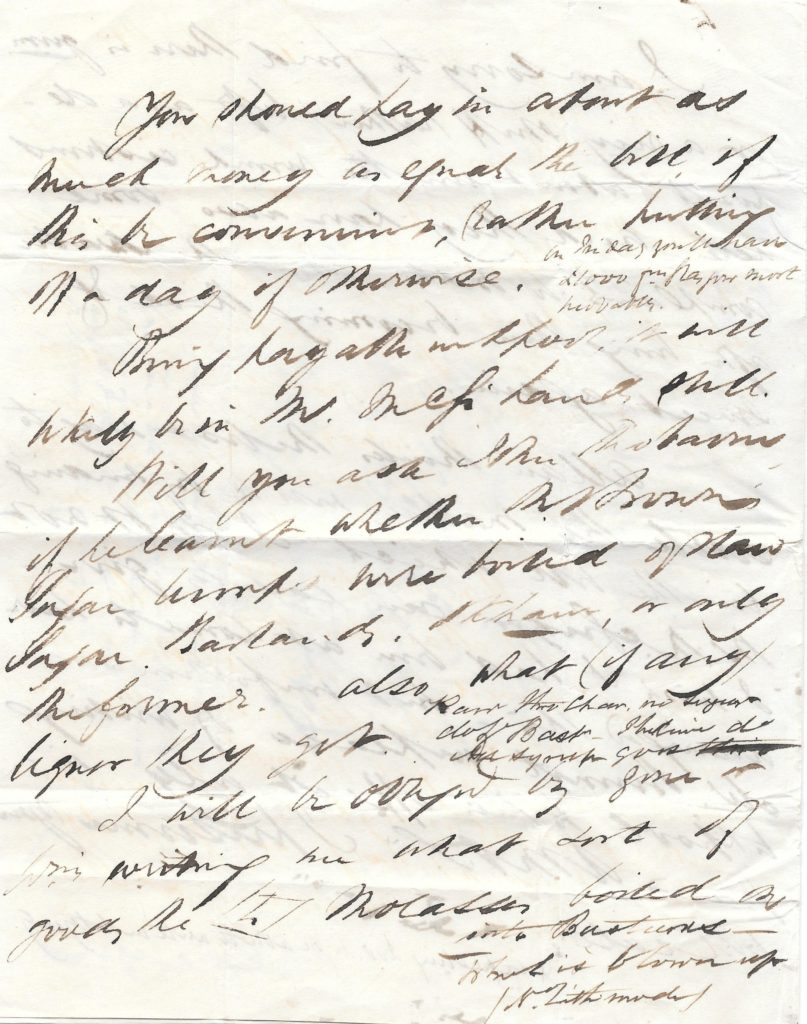

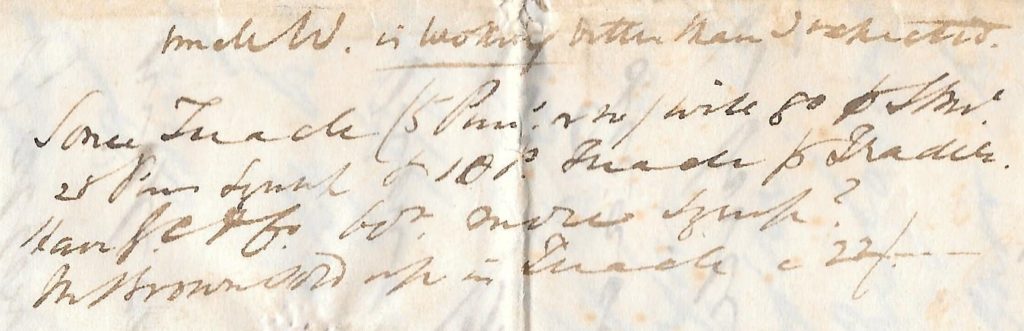

You should lay in about as much [malt? money?] as equal the bill if this be convenient, rather trusting in the day you have above for lay on most privately.

Bring together what you will wholly trust Mr. Balfour’s will.

Will you ask Mr. Graham if he learnt whether Mr. Brown before him ever tried to plow before backward, or only [Misfomer? Misformer?].

Also what (if any) [have thro them, no sugar old Backs, I should do the syrup extra strong liquor they get.]

I will be obliged by your writing me what sort of molasses, boiled as into best sugar, kind & flavour up.

J. Rutherford

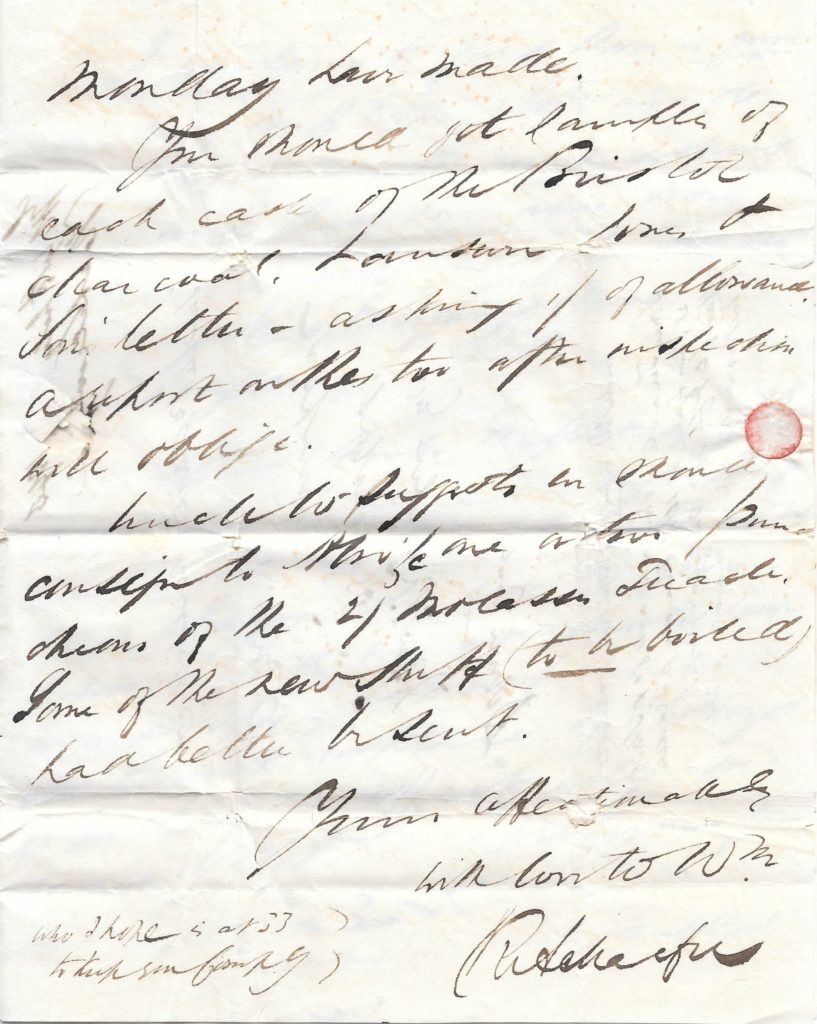

Monday was made.

You should get samples of black cake of the Bristol or clear coat. Landowners, too, & Jon’s letter – asking if allowance as for all the two after mischiefs will oblige.

Much W. suggests in Monday employ to strive and stir others of the 2d molasses, decide some of the new stuff to be boiled had better be sent.

Yours affectionately,

with love to Wm.

R. Rutherford

who I hope is at 33 to that [something family?]

Analysing the William Macfir Letter to John Macfir, 4 July 1843—Industrial, Familial, and Social Insights from a Victorian Correspondence

The William Macfir letter to his father John Macfir, dated 4 July 1843, stands as a fascinating document of mid-nineteenth-century Scottish life. Spanning several handwritten pages, the letter is both intimate and technical, combining the domestic concerns of a family in Greenock with the industrial and scientific preoccupations of a rapidly modernising Britain. Careful transcription and analysis of its content open a window onto the daily realities, professional anxieties, and interpersonal networks of the Victorian era.

I. Family and Social Connections

At the heart of the letter is the act of familial communication. William writes to reassure his father of safe arrival, not only of himself but also of several family members and household staff—“Caroline, the maids, servant & self arrived here well at 4 before 9, having had a good passage…” The reference to travel by boat, and the detailed account of each member’s health and disposition, underscores the hazards and uncertainties of travel before the era of widespread railways and steamships. The mention of “toothache,” “sickness,” and the relief of safe arrival reflect both the physical toll of travel and the strong concern for family wellbeing.

William’s tone is practical, but affectionate. He sends specific instructions for messages to be relayed to other family members and acquaintances (“On receipt you will do well to say to Dr. Malcolm that Charlotte & Florrie proved themselves excellent travellers…”). The frequent mention of family friends and associates—Mr. John Marquis, Charles Cunningham, R. Rutherford, and others—points to a close-knit network typical of Victorian professional and upper-middle-class families. The business of daily life, it seems, was inextricably linked with the maintenance of personal relationships.

II. Industrial, Technical, and Scientific Concerns

One of the most remarkable features of this letter is its technical and commercial content. William’s correspondence is filled with references to business arrangements, scientific experiments, and resource management—a hallmark of a period in which industrial innovation was transforming Scottish and British society.

For example, William discusses “travel arrangements, scientific or industrial testing, water supply concerns, and business instructions.” The reference to “seam tracks to break at any price it will bring” likely points to coal or mineral mining—a booming industry in 1840s Scotland. The anxiety over market prices and extraction methods is palpable, reflecting the pressure to innovate and remain competitive.

Similarly, there are passages concerning material quality and industrial process:

“J. Robinson forms some grain—but the mass, nor hardness nor texture, is so clayey in my opinion—but it does not alter my mind as to the channel, course of better stuff for the channel, which will affect the plan of treating.”

This sentence, while technical, speaks to debates over resource quality, the best uses for available materials, and the importance of continual testing and optimisation—ideas central to the Industrial Revolution. The mention of “oil formed in mass of this not named would assist burning” may refer to by-products of industrial processing or early experiments in fuel efficiency.

Further, the discussion of water—“the round cisterns here…and they have also more complaints to make about the water after being thus becoming thick & sweet again”—suggests ongoing issues with municipal water quality, likely a mixture of domestic and industrial concern. Water supply was a constant challenge in Victorian Britain, affecting not only health and hygiene but also the operation of factories and mills.

III. Business Operations and Decision-Making

Beyond scientific inquiry, William’s letter is also a document of business management. He writes about sales prospects, supply chain logistics, and market analysis. For instance:

“Has Atkin quite made a sale yet to Reading? + Roy has read the paper and suggests the pulps are true and high…”

Here, William is likely referencing negotiations for the sale or delivery of goods—possibly timber, grain, or processed materials. The technical and financial information in the letter shows that correspondence was a crucial tool for managing business in a world before instant communication.

Other passages, such as “You should lay in about as much [malt?] as equal the bill if this be convenient, rather trusting in the day you have above for lay on most privately,” further highlight the complexities of procurement and the need for private business strategies. The recurring mention of “molasses,” “distilling,” and related chemical processes also suggests involvement in the sugar trade, brewing, or distillation—industries heavily reliant on trade networks, material science, and precise record-keeping.

IV. Implications and Historical Context

The letter is valuable not only for its specific content but also for what it reveals about broader trends in Victorian Britain:

-

The Interplay of Family and Business: The Macfir family’s domestic life cannot be separated from their professional activities. Family members and servants are participants in the machinery of business, just as business decisions affect home life and travel plans.

-

The Spirit of Improvement: The text is suffused with the Victorian ethos of progress—testing, tweaking, and consulting experts (“I wish you would consult P. Graham re it”). There is a constant search for better methods, materials, and results.

-

Networks and Communication: William’s detailed instructions for passing messages, consulting colleagues, and relaying feedback reveal the importance of networks in a pre-telephone, pre-telegraph world. Letters were not just personal—they were instruments of business intelligence and collective decision-making.

-

Resource Management and Environmental Awareness: The concern for water quality, the mention of “clayey” materials, and the issues with supply (“damp to be made as spring…”) show an acute awareness of the environment and its impact on both home and industry. The letter also hints at early industrial environmental concerns, particularly with water and material waste.

V. The Value of the Letter Today

For historians and genealogists, the Macfir letter is a goldmine. It documents not only a family’s journey and business, but also the mindset of a transitional generation—caught between tradition and the relentless advance of industrial modernity. The blend of domestic, technical, and managerial detail is characteristic of the “total life” approach of the Victorian professional class.

For the modern reader, the letter serves as a reminder that technological and economic progress has always been built on networks of family, communication, and painstaking trial and error. The everyday struggles—health, travel, business worries—are as familiar as they are distant.

In summary:

The William Macfir letter to John Macfir is a microcosm of Victorian Scotland—deeply rooted in family, driven by industry, and animated by the ceaseless pursuit of improvement. Its contents, though at times cryptic to modern eyes, are a testament to the richness of everyday experience in an age of great change. As such, the letter stands not just as an archival artefact, but as a living conversation across the centuries.

For more on Victorian Scottish correspondence, visit the John Macfir archive collection. Discover additional rare letters and family records in our Old Days archive collections index.