A Letter from Southampton: Frank Edward Wright’s Childhood View of an Age in Motion

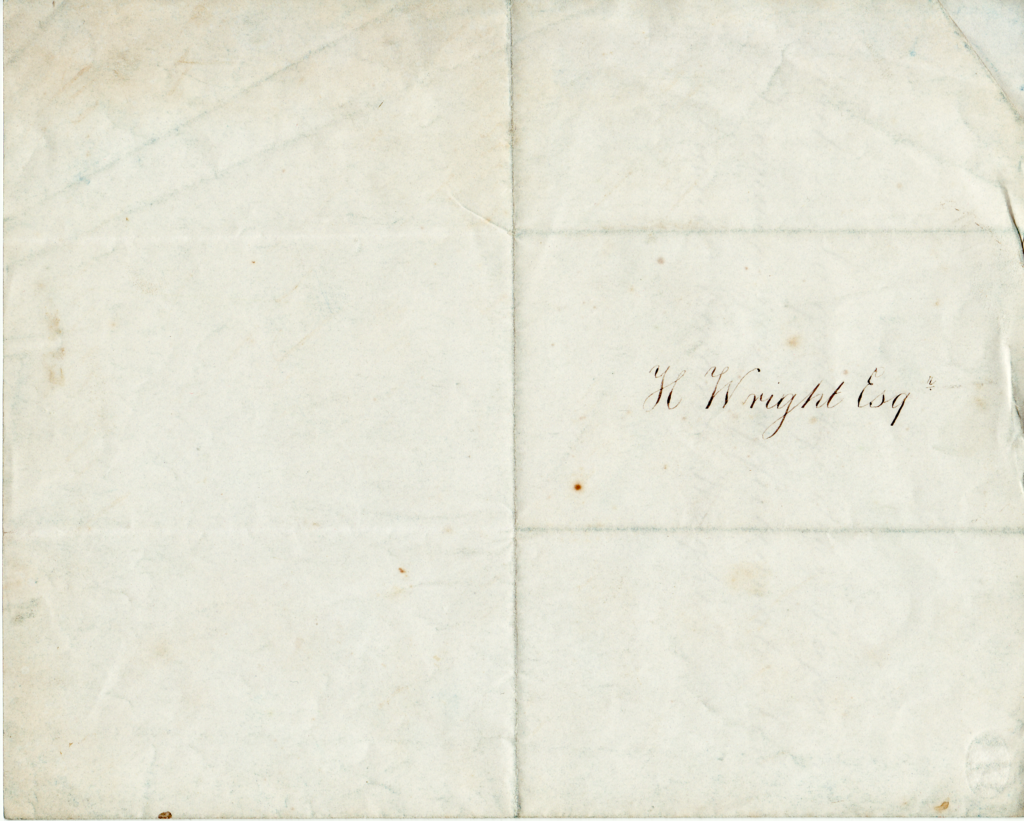

On the 17th of September 1842, a young boy named Frank Edward Wright sat down in Southampton and penned a letter to his father, H. Wright, Esquire. Though brief and innocent in tone, the letter stands as a window into a rapidly changing Britain—its society, technologies, and the global ambitions of its Empire. The letter survives today as a rare relic, offering both a family touchstone and a miniature documentary of the time.

On the 17th of September 1842, a young boy named Frank Edward Wright sat down in Southampton and penned a letter to his father, H. Wright, Esquire. Though brief and innocent in tone, the letter stands as a window into a rapidly changing Britain—its society, technologies, and the global ambitions of its Empire. The letter survives today as a rare relic, offering both a family touchstone and a miniature documentary of the time.

The Letter: A Child’s Perspective

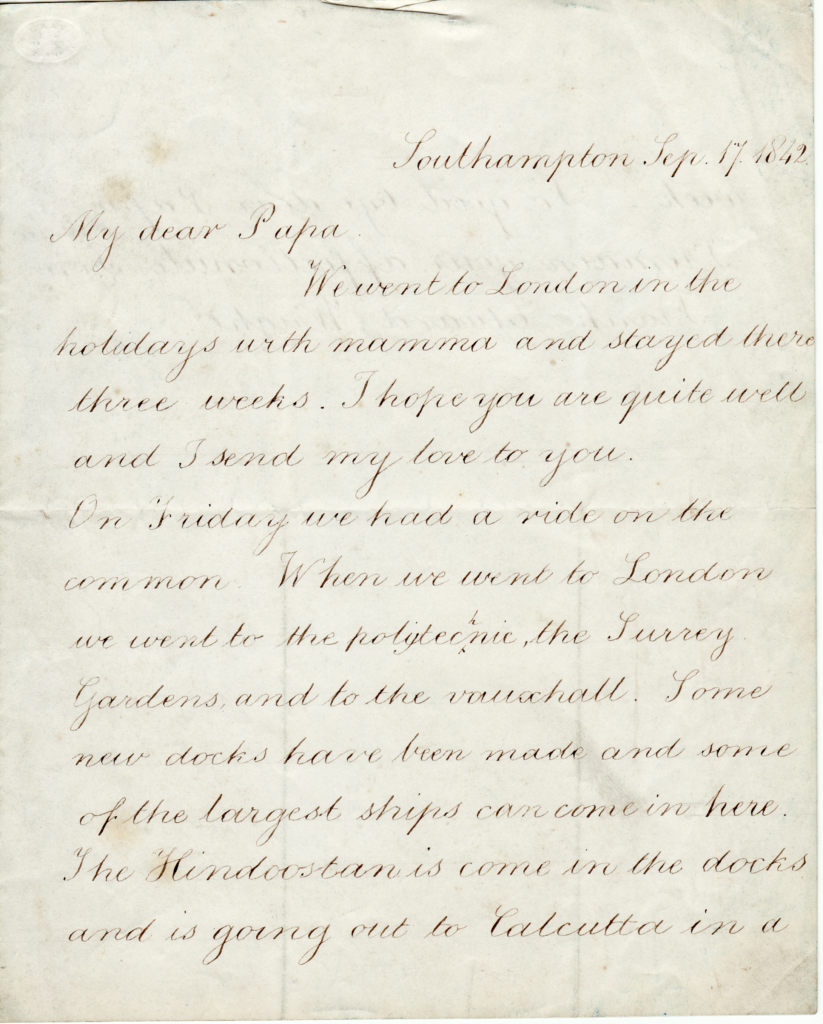

Frank’s letter reads with the clarity and candour of childhood. “We went to London in the holidays with mamma and stayed there three weeks. I hope you are quite well and I send my love to you,” he writes. He describes outings to the Polytechnic, the Surrey Gardens, and Vauxhall—places of entertainment, learning, and spectacle in the burgeoning metropolis of Victorian London. Even as a boy, Frank notes “some new docks have been made and some of the largest ships can come in here,” before mentioning the arrival of the Hindostan, “come in the docks and…going out to Calcutta in a week.”

Frank’s letter, though simple, captures a moment of family, progress, and personal excitement. His youthful pride in communicating these wonders to his father is unmistakable.

Southampton in 1842: A Hub of Change

In 1842, Southampton was experiencing one of its most transformative eras. Once a modest medieval port, it had become—by the 1840s—a key embarkation point for Britain’s growing empire and overseas connections. The expansion of the docks, which Frank references, was central to this new identity. Following the opening of the Southampton and London Railway in 1840, the town was now directly connected to the capital, making it a favoured port for both mail and passengers bound for India, Australia, and beyond.

The Polytechnic, Surrey Gardens, and Vauxhall: Victorian London’s Attractions

Frank’s trip to London with his mother is revealing of the kind of middle-class family they likely were—affluent enough to enjoy the cultural and scientific amusements of the age. The Royal Polytechnic Institution (opened in 1838) was a celebrated centre of public science demonstrations and exhibitions. The Surrey Zoological Gardens, created in the 1830s, were famous for their exotic animals and pleasure grounds, while Vauxhall Gardens—already a legend by the 1840s—offered evening entertainments, orchestras, and firework displays.

The Hindostan: A Ship of Empire

Of all Frank’s observations, his mention of the “Hindoostan” (usually spelled Hindostan) is most remarkable. The Hindostan was a 2,018-ton paddle steamer built for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), one of the most significant British shipping lines of the era. Launched in 1842, the Hindostan was among the first vessels to establish a regular steamer service between Southampton, Suez, Aden, and Calcutta, thus reducing travel times between Britain and India—the jewel in the imperial crown.

Frank saw the ship just before its maiden voyage: it departed Southampton for Calcutta on the 24th of September 1842, exactly one week after he wrote his letter. The Hindostan would play a crucial role in connecting Britain with its farthest dominions, symbolising a new age of steam-powered empire.

After two decades of service, the Hindostan was finally lost in a cyclone at Calcutta in 1864, where it had been employed as a store ship. Its story is one of innovation and ambition, but also the peril and fragility of Victorian maritime enterprise.

The Wright Family: A Mystery Partially Solved

Who were Frank Edward Wright and his family? The address “Southampton” and the respectful “H. Wright, Esquire” offer clues. The use of “Esquire” and the family’s leisure in London suggest a prosperous background—possibly in commerce, shipping, or the professions. The letter’s survival hints at a family that valued correspondence and memory.

While a definitive identification of Frank’s later life and family remains to be uncovered, the letter has prompted genealogical searches in Hampshire, shipping company records, and even contemporary passenger lists. There are several candidates for H. Wright in the region—merchants, shipowners, and solicitors—but as yet, no conclusive match.

The Value of the Letter: Childhood, Technology, and Empire

What makes Frank’s letter so resonant today is not merely its personal warmth, but its placement at the intersection of childhood and the grand sweep of history. It shows us how global change was observed, understood, and narrated by the very young—those whose lives would be shaped by the technologies, cities, and connections their age produced.

For the historian, such letters are priceless: they remind us that the stories of great ships, cities, and empires were also the stories of individuals—children, families, and the everyday bonds that endure in fragile ink across centuries.

Suggestions for Further Research

-

Genealogical Inquiry: Examine parish records, census returns, and directories in Southampton and London for Wright families, c. 1840–1860.

-

Shipping Records: Search P&O and port of Southampton archives for mentions of the Wright family in connection with the docks or shipping interests.

-

Victorian Children’s Letters: Compare Frank’s letter to other surviving childhood correspondences from the period, highlighting themes of technology, travel, and family.

Sources Consulted

-

The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company and the Rise of British Imperial Shipping, National Maritime Museum archives.

-

Southampton: Gateway to the Empire by Peter L. Williams.

-

The London Encyclopaedia by Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert (on London attractions).

-

Census and parish records, Southampton Archives, Hampshire Record Office.

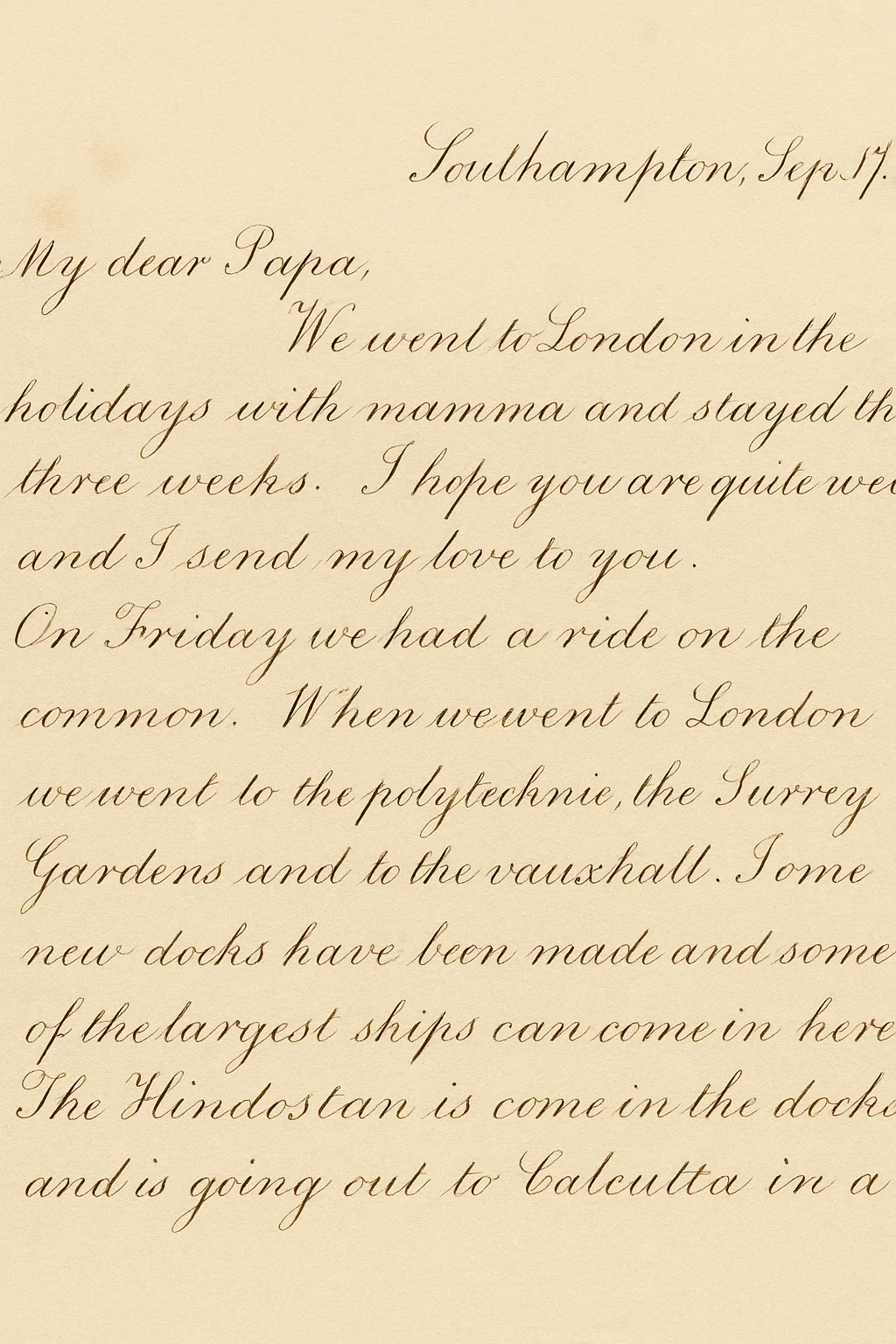

“Southampton September 17, 1842

My dear Papa,

We went to London in the holidays with mamma and stayed there three weeks. I hope you are quite well and I send my love to you.

On Friday we had a ride on the common. When we went to London we went to the Polytechnic, the Surrey Gardens and to the Vauxhall. Some new docks have been made and some of the largest ships can come in here. The Hindoostan is come in the docks and is going out to Calcutta in a week. So goodbye dear papa.

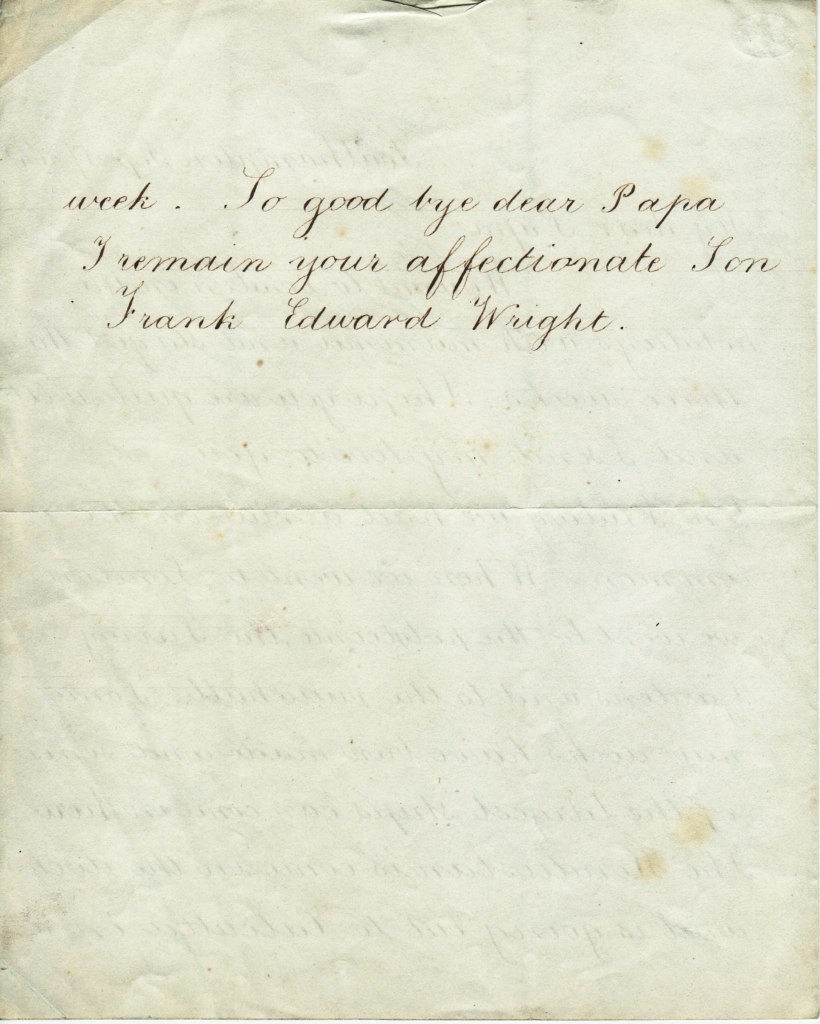

I remain your affectionate son.

Frank Edward Wright”

Frank had seen the “Hindustan” just days before it set sail on it’s first trip. The “Hindustan”, 2,018 tons left Southampton on her maiden voyage, 24th September 1842, to Calcutta where she set up a regular service from there to Aden and Suez to link up with passengers travelling from Southampton to Alexandria, who then travelled overland to Suez. It sank in a cyclone in Calcutta in 1864 while employed as a store ship.

I acquired Frank’s letter to his father and have been trying to trace his family history.