This research, as a result of a letter I acquired in 2018, examines a long-term land dispute over Ashdown Forest in Sussex, culminating in the 1880 court case Earl De La Warr v. Miles and Others. The case centred on the legal status of commoners’ traditional rights—such as grazing, turf-cutting, and wood gathering—versus the claims of the manor’s landowners. The ruling redefined access to the forest, stripping many local residents of customary uses unless supported by clear legal evidence, and reshaped the balance between public use and private control of common land.

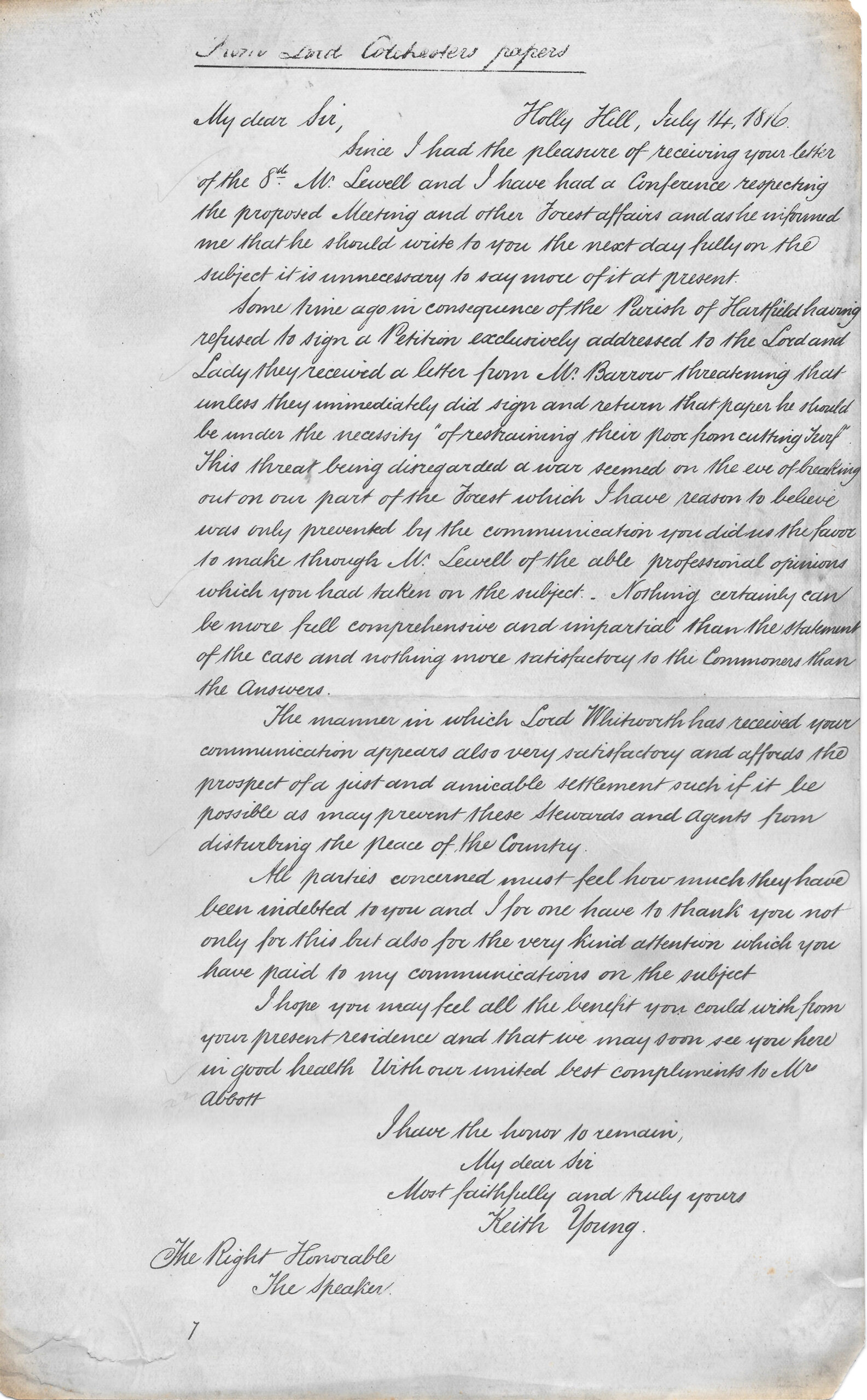

The letter is dated July 14, 1816 and written by Keith Young to The Right Honourable The Speaker, regarding the local dispute over forest rights.

Here’s a clear explanation of the key elements:

Summary of Content

1. Context and Main Subject:

-

The letter is part of a broader correspondence about forest usage rights, particularly the letting (leasing) of parts of the forest and access to resources such as turf (peat).

-

A prior letter from “Mr. Sewell” and a meeting between him and Keith Young discussed proposed lettings and other forest affairs. Mr. Sewell was expected to write a detailed follow-up.

2. The Hartfield Parish Incident:

-

Residents of Hartfield, a parish within or near Ashdown Forest, refused to sign a petition addressed to the Lords and Lady (likely referring to the forest’s landowners or stakeholders).

-

In response, Mr. Barrow (likely an agent or steward for the landowners) threatened that unless they signed the petition, the poor of Hartfield would no longer be allowed to cut turf for fuel—a critical right at the time.

-

This was seen as an oppressive move, and resistance was building among commoners.

3. Averting Escalation:

-

Keith Young implies that tensions were rising and a conflict was almost inevitable (“a war seemed on the eve of breaking out”).

-

However, it was avoided thanks to a legal opinion the Speaker had sought and shared via Mr. Sewell. This legal statement was seen as fair, clear, and supportive of the commoners’ rights.

4. Lord Whitworth’s Reaction:

-

Lord Whitworth (possibly Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth) received the communication well, giving hope for a peaceful and just resolution that would prevent land agents and stewards from disturbing rural peace.

5. Gratitude and Personal Wishes:

-

Young expresses deep gratitude to the Speaker for his efforts, not only for the legal support but also for his attention to communications.

-

He ends by wishing the Speaker good health and hoping he will return from his current residence.

Historical Context

-

Ashdown Forest is a historically contested common land in Sussex. Its use has long involved disputes between commoners (local residents with traditional rights) and landowners (Lords of the Manor, nobility, and their agents).

-

Cutting turf, grazing animals, and gathering wood were vital to poor rural families and were protected rights, though constantly under threat by enclosure or privatisation attempts.

-

This letter shows a high-level political intervention (via the Speaker of the House of Commons) to protect these rights.

Key Figures Mentioned

| Name | Role/Significance |

|---|---|

| Keith Young | The letter’s author; likely an advocate for local rights or an intermediary. |

| Mr. Sewell | A legal advisor or mutual contact aiding with the dispute. |

| Mr. Barrow | A steward or land agent enforcing the petition and turf restriction. |

| Lord Whitworth | High-ranking noble; his approval signals support for resolving the issue amicably. |

| The Speaker | Recipient of the letter; a powerful political figure taking an interest in the matter. |

Why This Matters

This letter is a rare window into land rights activism, social justice, and rural politics in early 19th-century England. It shows:

-

Resistance by rural parishes to unfair pressure.

-

The role of legal counsel and political support in protecting traditional rights.

-

The growing tension between local communities and powerful estate interests during a period when enclosure movements and privatization were widespread.

My dear Sir,

Since I had the pleasure of receiving your letter of the 8th Mr Lewell and I have had a conference respecting the proposed meeting and other Forest affairs and he has informed me that he should write to you the next day for a on the subject of it is unnecessary to say more of it at present.

Some time ago in consequence of the parish of Hartfield having refused to sign the petition exclusively addressed to the Lord and Lady they received a letter from Mr. Barrow threatening that unless they immediately did sign and return that paper he should be under the necessity of “restraining their poor from cutting turf”. This threat being disregarded a war seemed on the eve of breaking out in our part of the forest which I have reason to believe was only prevented by the communication you did us a favour to make sure Mr. Lewell of the able professional opinions which you had taken on the subject. Nothing certainly can be more full comprehensive and impartial land the statement of the case and nothing more satisfactory to the commons than the answers.

The manner in which Lord Whitworth has received your communication appears also very satisfactory and affords the prospect of a just and amicable settlement such if it be possible and may prevent these Stewards and agents from disturbing the peace of the country.

The parties concerned and must feel how much they have been indebted to you and I for one have to thank you not only for this but also for the very kind attention which you have paid to my communications on the subject.

I hope you may feel all the benefit you could wish from your present or residence and that we may soon see you here in good health with are united best compliments to Mrs. Abbot .

I have the honor to remain

My dear sir

Most faithfully and truly yours

Keith Young

Right Honorable

The speaker

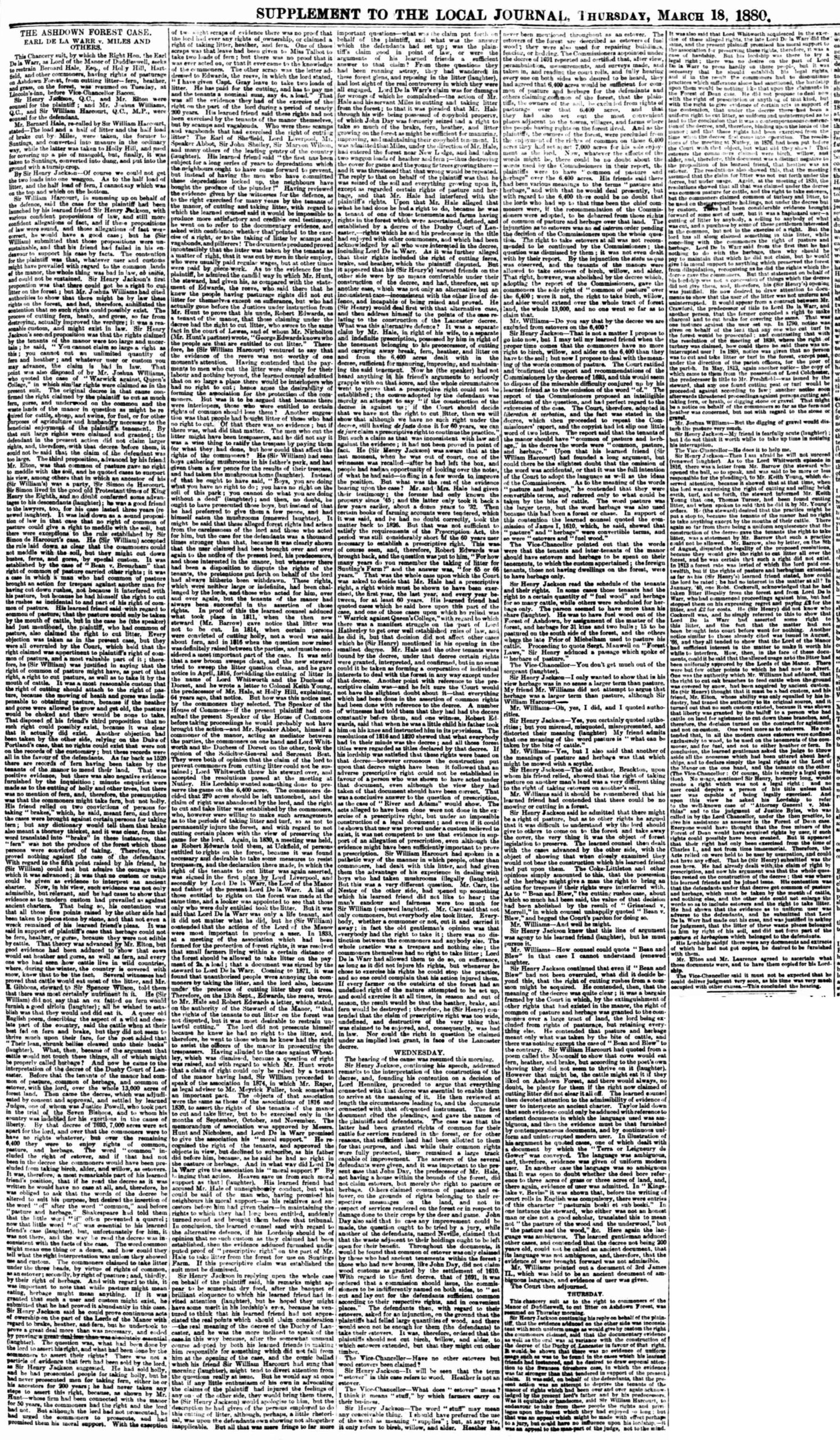

Sutton Journal – Thursday 18 March 1880

THE ASHDOWN FOREST CASE, EARL DE LA WARR v. MILES AND OTHERS (partial transcription due to poor text quality).

The Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice, Vice-Chancellor Hall sitting, resumed on Monday, March 15th, the hearing of this important suit, which was originally instituted by the Earl De La Warr and the Rev. John Boscawen, rector of Withyham, as Lords of the Manor of Duddleswell, and owners of the soil of Ashdown Forest, against the representatives of certain freehold and copyhold tenements claiming rights of common of pasture and of estovers over the said forest.

The defendants included Mr. William Hall, farmer, of Fords Green, Nutley; Mr. Thomas Miles, farmer, of Fairwarp; and Mr. Edward Miles, of the same place.

Mr. Glasse, Q.C., and Mr. Kekewich (instructed by Messrs. White and Borrett), appeared for the plaintiffs.

Mr. Kay, Q.C., and Mr. Ince (instructed by Messrs. Prior and Rickman), for the defendant Hall.

Mr. Baggalay, Q.C., and Mr. H. W. Macnamara (instructed by Messrs. Dunn and Langton), for the defendants T. and E. Miles.

Mr. Glasse, Q.C., continued the case for the plaintiffs. He said this was a case of great importance not only to the parties, but to the public generally. It raised questions of large principle and permanent interest. The plaintiffs asked that the rights of the commoners be ascertained and defined, and that a scheme be settled for the better management and regulation of the forest and the rights thereon. The plaintiffs were the lords of the manor of Duddleswell and owners of the soil of Ashdown Forest. They admitted that certain persons were entitled to rights of common, but those rights must be reasonable and defined, and not vague and unlimited, as the defendants contended. He then read a number of extracts from ancient records, dating as far back as the time of Henry III, and argued that from these it appeared that the forest was always regarded as waste land belonging to the Crown, and subject to certain common rights of the tenants of the manor.

The object of the plaintiffs was not to interfere with the just rights of any person, but to ascertain what those rights were. They did not deny the existence of rights of common of pasture and of estovers, but contended that those rights must be exercised under reasonable regulations, and with due regard to the preservation of the forest. It was not a question of right or title to the soil of the forest; that was clearly vested in the plaintiffs. The question was as to the extent and mode of user of the rights of common. The plaintiffs had issued circulars and notices to the tenants of the manor calling upon them to state the nature and extent of the rights claimed by them, and offering to treat with them for the purpose of defining those rights. A large number had responded to this appeal, and arrangements had been made with them. But others had declined to come to any terms, and some had assumed rights which they could not prove. This rendered it necessary to take legal proceedings. The Vice-Chancellor had already made a decree ordering an inquiry before one of the chief clerks, and it was in the course of that inquiry that the questions now in dispute had arisen.

In 1852, a report was made by the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, which gave a detailed account of the forest, its history, and condition. It stated that the forest then contained about 6,000 acres, and that the rights of common were claimed in respect of about 1,200 tenements. The report suggested that the forest should be inclosed and a portion allotted to the commoners, but this suggestion was not adopted. Instead, it was proposed to preserve the forest as an open space, subject to proper regulation. In 1879, the plaintiffs obtained a decree from the Court of Chancery ordering an inquiry into the rights of common claimed over the forest, and directing that such rights, if established, should be ascertained and defined.

In pursuance of this decree, notices were issued and claims were lodged by many persons. Among these were the defendants, who set up rights of common of pasture and of estovers in respect of certain lands held by them. These claims were investigated, and the plaintiffs contended that the defendants had failed to prove the existence of such rights, or that they had been lawfully exercised. The plaintiffs relied on the fact that in many cases the alleged user was of recent origin, and was not supported by sufficient evidence of custom or prescription.

Mr. Glasse then examined various ancient documents, including Court Rolls, surveys, and maps, to show the true character of the forest and the rights exercised over it. He pointed out that the forest was never enclosed, and that the supposed rights of the defendants could not have existed without express grant or long-established custom. In many instances the user was shown to have originated within the last 40 or 50 years, and was evidently the result of permission or tolerance on the part of the lords of the manor, rather than of legal right.

He next dealt with the evidence given on behalf of the defendants, and contended that it was vague, contradictory, and insufficient to establish any legal right. In one case, a witness had stated that he had cut litter for 20 years, but on cross-examination it appeared that he had only done so by permission, and had never claimed it as a right. In another case, the claim was based on a single act of user which occurred long after the alleged right had been abandoned.

The Vice-Chancellor had to consider whether the defendants had shown such continuous and lawful user as would establish a legal right of common. The plaintiffs said they had not, and that, therefore, they should be restrained from exercising any such claims. At the same time, the plaintiffs expressed their willingness to make arrangements with any person who could show a reasonable title to common rights.

Mr. Kay, Q.C., for the defendant Hall, submitted that his client was entitled to the rights he claimed by reason of long-continued user and local custom. He referred to various acts of user by his client and his predecessors in title, and argued that these acts, taken together, amounted to a sufficient legal foundation for the right of common. He also contended that there was nothing in the plaintiffs’ evidence to disprove the existence of such a right. On the contrary, the admissions made by the plaintiffs tended to confirm it.

Mr. Baggalay, Q.C., for the defendants Thomas and Edward Miles, followed on the same lines. He insisted that the claims of his clients were well founded in law and fact, and supported by ample evidence. He denied that there had been any abandonment of the rights, and asserted that the acts of user had been continuous and as of right. He concluded by urging the court not to disturb long-established rights without the clearest proof that they had no legal existence.

Mr. Glasse, in reply, said the plaintiffs had no desire to do anything unjust or oppressive. They simply asked that the forest might be properly regulated, and that such persons as had no legal rights should not be allowed to injure the interests of those who had. The plaintiffs had already come to terms with many of the commoners, and were ready to deal fairly with others. But it was essential that the claims should be examined and determined in a legal manner, and not left to vague assertion or popular belief.

His Honour the Vice-Chancellor, in giving judgment, said that the case was one of much importance, not only to the parties immediately concerned, but to the public generally, as it affected a large and valuable tract of open country in a populous district. He had carefully considered the evidence and arguments on both sides, and had come to the conclusion that the plaintiffs were entitled to the relief they sought. The defendants had failed to establish any legal right of common over the forest lands in question. The evidence of user was insufficient, vague, or too recent in origin to sustain the claims set up.

His Honour made an order restraining the defendants from exercising the alleged rights of common, and directing that the costs of the suit be borne by them. At the same time, he expressed a hope that the plaintiffs would act with fairness and forbearance in dealing with the other commoners, and would be guided by a desire to maintain the forest as a public benefit.

This decision is likely to be received with satisfaction by those interested in the preservation of Ashdown Forest, and will probably lead to further measures being taken to secure its proper regulation and enjoyment.

The Ashdown Forest Case – Analysis

Earl De La Warr v. Miles and Others

Reported in the Sutton Journal – Thursday, 18 March 1880

The Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice, Vice-Chancellor Hall presiding, resumed on Monday, March 15th, the hearing of this important suit, which was originally brought by the Earl De La Warr and the Rev. John Boscawen, rector of Withyham, as Lords of the Manor of Duddleswell and owners of the soil of Ashdown Forest, against representatives of certain freehold and copyhold tenements who claimed rights of common of pasture and of estovers over the forest.

The defendants included Mr. William Hall, farmer, of Fords Green, Nutley; Mr. Thomas Miles, farmer, of Fairwarp; and Mr. Edward Miles, also of Fairwarp.

Legal Representation:

-

For the plaintiffs: Mr. Glasse, Q.C., and Mr. Kekewich (instructed by Messrs. White and Borrett)

-

For Mr. Hall: Mr. Kay, Q.C., and Mr. Ince (Messrs. Prior and Rickman)

-

For T. and E. Miles: Mr. Baggalay, Q.C., and Mr. H. W. Macnamara (Messrs. Dunn and Langton)

The Plaintiffs’ Case

Mr. Glasse, Q.C., stated that the suit was of great public importance, raising principles of lasting interest. The plaintiffs sought to have the rights of commoners ascertained, defined, and brought under a scheme of regulation for the preservation of the forest. While acknowledging that some persons held genuine common rights, the plaintiffs argued that these must be reasonable and specific — not vague and unlimited as claimed by the defendants.

Referring to ancient records, including documentation dating to the reign of Henry III, Mr. Glasse contended that Ashdown Forest was historically considered waste land belonging to the Crown, and only subject to certain rights by tenants of the manor.

Historical Context and Legal Action

The plaintiffs had issued notices requesting tenants to declare their rights, leading many to amicable agreements. However, some refused and others asserted rights without sufficient basis. This compelled the plaintiffs to seek judicial relief.

A report by the Commissioners of Woods and Forests in 1852 stated the forest contained approximately 6,000 acres, with about 1,200 tenements claiming common rights. Though enclosure was considered, a decision was made to retain the forest as open land with regulated access. In 1879, a decree was granted directing that all claimed rights be formally examined.

Disputed Claims

As part of the resulting inquiry, various individuals submitted claims, including the defendants, who asserted rights of pasture and estovers. The plaintiffs maintained these claims were either unsupported by custom or only recently practiced — often by mere tolerance of the manor.

Mr. Glasse cited court rolls, surveys, and maps to show the lack of lawful, long-standing use. Some defendants had only used rights for a few decades, often admitting this was with permission and not legal entitlement.

The Defence

Mr. Kay, Q.C., argued on behalf of Mr. Hall that his client’s rights were grounded in long-standing custom and continuous use. Mr. Baggalay, Q.C., representing the Miles defendants, echoed this, asserting that the claims were lawful and not abandoned. He urged the court not to disturb established traditions without overwhelming evidence.

The Judgment

Vice-Chancellor Hall, in delivering judgment, acknowledged the case’s significance to the public as well as the parties. After reviewing the evidence, he concluded that the defendants had failed to prove any legal rights of common. The user was either vague, too recent, or not shown to be lawful.

He granted an injunction restraining the defendants from exercising the claimed rights and ordered them to bear the costs of the suit. Nonetheless, he urged the plaintiffs to act with fairness towards remaining commoners and preserve the forest as a public benefit.

Commentary

This ruling is expected to be welcomed by those concerned with preserving Ashdown Forest and may lead to further steps to ensure its proper regulation and public enjoyment.

1. Loss of Informal Rights

-

Many rural households had relied for generations on customary, informal use of the forest — grazing animals, cutting turf for fuel, gathering wood, and taking bracken or litter for animal bedding.

-

The ruling invalidated unproven or vague claims, meaning that unless a right was explicitly documented and legally recognised, it was effectively lost.

-

Those who had quietly relied on “use by tolerance” from the lords of the manor could no longer assume access.

2. Economic Hardship for the Poor

-

For small farmers and cottagers, these rights were economically essential:

-

Grazing reduced the need to buy feed.

-

Turf and wood provided free heating and cooking fuel.

-

Bracken and gorse were used for bedding, thatch, and fencing.

-

-

Without legal rights, they would now need to pay for these resources — adding to rural poverty.

-

Loss of fuel rights in particular could be devastating during harsh winters.

3. Greater Control by Estate Management

-

The ruling strengthened the lords of the manor’s legal power over the forest.

-

This gave them the authority to:

-

Restrict access.

-

Enforce conservation or commercial schemes (e.g., timber sales).

-

Lease land for grazing or other use on their terms.

-

-

It effectively shifted the balance of power from local commoners to the estate hierarchy.

4. Social and Community Impact

-

The decision could fuel resentment and tension between estate officials (stewards, agents) and local villagers.

-

Some families who believed they had ancestral rights would see the judgment as an attack on tradition.

-

Those who had negotiated settlements with the plaintiffs might be viewed with suspicion or resentment by neighbours who fought the case and lost.

5. Preservation and Regulation

-

From a conservation point of view, the judgment reduced over-exploitation:

-

Unchecked cutting of turf, wood, and vegetation had degraded some areas.

-

Regulation meant less immediate environmental damage.

-

-

However, in 1880, the modern idea of environmental protection was secondary to maintaining estate value.

6. Long-Term Legal Precedent

-

The case set a clear precedent for common rights disputes in other parts of England.

-

It reinforced that continuous use alone was not enough; there had to be evidence of lawful origin (by grant, immemorial custom, or prescription).

-

This precedent could later be used to challenge similar rural communities elsewhere.

Summary of Everyday Consequences

For residents:

-

Some lost direct access to essential grazing and fuel.

-

Household costs increased as they had to buy what they once gathered for free.

-

A sense of traditional entitlement was replaced by dependence on permissions or leases.

For workers:

-

Estate employees (woodmen, gamekeepers) gained more authority in enforcing restrictions.

-

Farmers with proven rights benefited from a clearer, legally recognised framework, but those without proof lost out entirely.